During the days and weeks that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine, thousands of women and children crossed the borders into the EU. Registration of children, particularly those who could be traveling unaccompanied, proved challenging. Gaps persist in the referral of children displaced from Ukraine to national child protection authorities, as documented in previous FRA reports, including its previous bulletins and the 2023 Fundamental Rights Report.

Under Article 10 of the TPD, Member States must register personal data of people who register for temporary protection on their territory. Personal data includes name, nationality, date and place of birth, marital status, and family relationship. As part of the 10-Point Plan for stronger European coordination, on 31 May 2022 the European Commission launched a platform for the registration of temporary protection beneficiaries enabling exchange of information between Member States to avoid double registrations and limit possible abuse. This platform serves as the only EU-wide point of reference for Member States, as large-scale EU IT systems and databases, such as Eurodac, cannot be used for registration of beneficiaries of temporary protection. The European Commission advised Member States to register temporary protection beneficiaries in existent national registers for in full respect of the General Data Protection Regulation (EU 2016/679).

Various approaches exist across the EU regarding the design and operation of registration systems and the authorities responsible. Within Member States there are also different systems and procedures applied for registration of adults, of children and specifically of unaccompanied children displaced from Ukraine.

In most Member States, migration authorities register people fleeing Ukraine seeking temporary protection. Data are recorded in the same national databases used for all persons seeking international protection. An EUAA report outlines the general registration procedures, the responsible authorities and processing times.

Responsibility for registration rests at the level of municipalities and local administrative authorities in France, the Netherlands and Slovenia.[6] European Commission (2023), Providing Temporary Protection to Displaced Persons from Ukraine: A Year in Review (europa.eu), p. 20.

In the Netherlands, registration takes place at the 25 Safety Regions, which refers displaced persons to a municipality that receives them. Once they are resident, they must register at the national Personal Records Database. A report by Defence for Children found that as no central registration takes place due to the decentralised reception and “the overarching perspective and overview when it comes to screening for vulnerability and care needs is often lacking.”

There are often multiple authorities involved in the registration procedure. In Germany, for example, the Reception Centres, Foreigners’ Offices, or the police carry out the registration of people displaced from Ukraine. Families arriving with children must get in touch with the Youth Welfare Office as early as possible. In the case of unaccompanied children, it is the registering authority which contacts the Youth Welfare Office directly. The latter communicates the number of children (accompanied and unaccompanied) registered in the federal state to the Federal Office of Administration. Two specific offices were set up: one for the reception of children evacuated from institutions, coordinated at federal level, and one for larger groups of persons with disabilities (see Chapters 6.1 and 6.2).

Due to many actors with different competences being involved in registering displaced people, there are multiple registration systems and databases that hold different parts of the recorded information in Member States. For example, in Belgium, information on displaced people, including children, is stored in the Population Registries, the database of the Immigration Office (Evibel), the internal database of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, and the internal database of the Federal Asylum Agency (Fedasil). There is no single system or database to identify all children.

The lack of cross-referencing between data registers could result in discrepancies. For example in Latvia, the Population Register includes all permanent residents, including those under temporary protection. Another register, the Register of Information Necessary for Providing Support to Ukrainian Civilians, contains information on Ukrainian people who applied for social services and allowances to governments of local municipalities. The total number of registered children varies across these registers.[7] Information received from the Latvian Ministry of Interior by email on 14 June 2023.

In Bulgaria, the State Agency for Child Protection maintains a register of all children displaced from Ukraine, including those who came with their parents or legal guardians. Also in Romania, a dedicated application, PRIMERO, is used to identify and register Ukrainian children seeking protection in Romania.

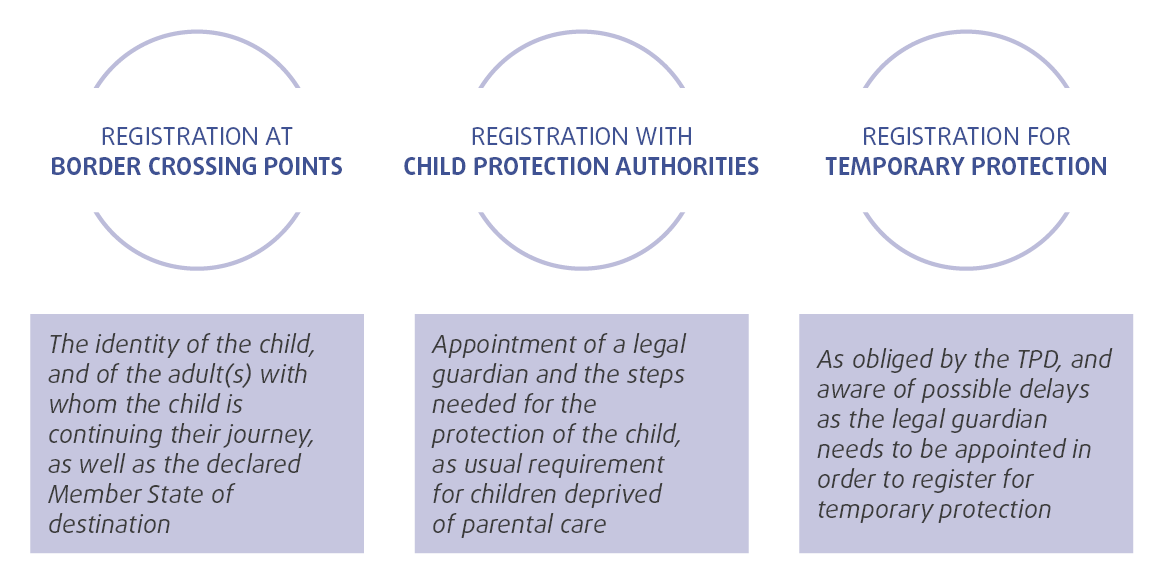

The European Commission outlined three types of registration that are essential to ensure a child’s safety in its operational guidelines for implementation of the TPD and the FAQs on registration, reception and care of unaccompanied children. These are: initial registration at the border, registration with the national child protection authorities, and registration for temporary protection, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Registration for unaccompanied and separated children

A graphic presents the three types of registration of unaccompanied children essential to ensuring a child’s safety: initial registration at the border, registration with the national child protection authorities and registration for temporary protection.

Source: European Commission and a FAQ on unaccompanied children.

The existence of a special registry for children displaced from Ukraine “is not indispensable - what ultimately matters is to ensure that the child is registered with the child protection services”, according to the European Commission.

Data are not comparable between Member States as there is no unified system across the EU, and procedures and definitions used to register children differ between Member States. About a third of the EU Member States categorise accompanied, separated and unaccompanied children separately for registration purposes.

For example, in Sweden, the Migration Agency publishes statistics on each category, where data can be obtained. As of 28 May 2023, 863 unaccompanied children were granted residence permits. Of these, 801 were separated children and 62 had arrived unaccompanied.[8] Sweden, e-mail correspondence with legal expert at the Migration Agency, 14 June 2023.

Other Member States, for instance Belgium, Denmark and Finland, categorise and register separated children as unaccompanied children. There are few examples of separate registration for children who arrived in groups. In Poland, registration is only obligatory for unaccompanied children and those who are part of an organised evacuation from institutions or foster care.

Several Member States have specific registries for unaccompanied migrant children. Most often, countries which experience large numbers of arrivals of unaccompanied children have these kinds of registries. In Italy, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies monitors unaccompanied migrant children and collects and reports data to a central Child Information System database. The Greek National Emergency Response Mechanism (NERM), tasked with protection for and reception of all unaccompanied and separated children, has a dedicated register for unaccompanied and separated children fleeing Ukraine. A specific registration procedure[9] Greece, the information was provided by the Greek Special Secretary for the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors through a written contribution on 12 June 2023.

is triggered when an unaccompanied or separated child arriving from Ukraine enters Greece.

In some Member States, responsibility for registration is shared among different authorities. For example, in Slovakia and Estonia, border and police authorities manage the data on arrivals and residence permits and social protection authorities manage data on unaccompanied children.

Latvia and Poland created platforms to record unaccompanied children fleeing Ukraine in respective national laws. In Latvia, the Law on Assistance to Ukrainian Civilians, prescribes that the State Inspectorate for Protection of Children's Rights maintains a unified register of unaccompanied children. Also in Poland, according to Article 25a of the Law of 12 March 2022 on Assistance to Citizens of Ukraine in Connection with the Armed Conflict on the Territory of Ukraine children who are unaccompanied and those who were previously in foster care in Ukraine must be registered in a ‘register of minors’.

While progress has been made in the 18 months since the Russian invasion, there remains lack of comprehensive EU-wide data on displaced children in Member States. Specifically, there is a lack of data on the number of children, how they are categorised and the number in each category in each Member State.

Temporary protection beneficiaries have the right to move freely before and after a residence is issued under certain conditions. If a person subsequently moves to another Member State and receives another residence permit, the first residence permit and its ensuing rights must expire and be withdrawn, in accordance with the spirit of Articles 15(6) and 26(4) of the TPD.

Given this complexity, aggregated data on children displaced in the EU is not comparable between the Member States. There are a variety of registration systems which hold different types of personal data depending on the authorities’ competences.

A compilation of national data reported to FRA on the overall number of children displaced in each Member State is available in Annex 1. Information on children who were evacuated from institutions in Ukraine is presented in Chapter 6.1.

Most EU Member States report monthly statistics to Eurostat as part of a voluntary agreement. Regarding the number of children who receive temporary protection, nine EU Member States (Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden) publish data on publicly available websites, national statistical offices, or migration information systems.

Some Member States, for example Denmark, Lithuania and Sweden, have publicly available databases of persons displaced from Ukraine that allow for disaggregation by sex and by different age groups below 18 years of age.

In other Member States, public authorities provide information about children. For example, in Germany the Central Register of Foreigners published a factsheet on refugee children from Ukraine and the Ministry for Family Affairs produced a dedicated report on unaccompanied children’s situation in Germany.

Data on people displaced from Ukraine in Ireland is compiled weekly by the Central Statistics Office The government receives a detailed report, while selected data on Ukraine statistics is publicly available. It includes details on unaccompanied children referred to Tusla (the Child and Family Agency), beneficiaries of social welfare, and education enrolment.

In Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechia, Finland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovakia, Spain and Poland, FRA’s research network had to request information from the competent authorities. There was no publicly available data on the number of children displaced from Ukraine in each respective Member State.

In four Member States, France, Slovenia, Spain and Romania, FRA’s research network did receive information they requested within the timeline of data collection for this research. For more details on each country see Franet national reports.

A wide variety of approaches exist across the EU in terms of regularity and frequency of updating available data on registrations and granted temporary protection. Data are updated monthly in Austria, Greece and Italy, and weekly in Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden. In Denmark, information about people displaced from Ukraine who have been granted residence permits is published on a monthly basis by the Immigration Service in accordance with the ‘Special Act’ legislation. Statistics Denmark provides data quarterly.

Data received by Franet for this research refers in general terms to the overall number of children registered for temporary protection in the country, rather than giving precise information. This is the case for the information received from the authorities in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary and Slovakia. In Bulgaria, the State Agency for Child Protection provided a figure of 53,867 children in the country, but this refers to the overall number of children granted temporary protection since the beginning of the war until 9 June 2023. Denmark’s data refer to the current number of children with Ukrainian nationality living in Denmark, including children who arrived in Denmark before 24 February 2022.

The lack of up-to-date and comprehensive data has been criticised by civil society in Bulgaria, who called for the collection of more precise data on vulnerable groups of children to provide targeted support.

Some Member States have several different registers of children displaced from Ukraine (see Chapter 2.1). In Latvia, for example, in addition to the unified register of unaccompanied children, the Population Register contains information about permanent residents in Latvia and includes children to whom temporary protection has been awarded. However, it does not indicate how many people are currently in Latvia as they can move freely within the EU or return to Ukraine without renouncing their temporary protection status. Another register lists the Ukrainians who have applied for types of social services and support. Regarding children, there is a register that collects data to provide support to Ukrainians, gathering information on the people who arrive with the child, the level of education that the child has obtained and their plans to continue education in Latvia. The register also indicates how many children have a disability and require medical assistance or special services, as reported by the person.

Similarly, in Ireland there is a register on the number of parents or guardians receiving child welfare benefits among arrivals from Ukraine. This is in addition to the statistics available on the number of children allocated a personal public services number (PPSN) which enables them access to some public services.

Lack of disaggregation by age and sex may hinder the development of targeted measures in Member States. The data provided by national authorities to FRA’s research network differ in terms of the level and type of disaggregation. Approximately one third of Member States provide age disaggregated data, often distinguishing between children under 13 and those aged 14 to 17. Some Member States like Cyprus, Finland and Latvia use more detailed age categories.

Data disaggregated by sex is available in about half of the Member States, mostly using binary representation except for Belgium. Certain Member States like Greece, Luxembourg, Portugal and Finland provide disaggregated data based on nationality. This enables identification of children who fled Ukraine but do not hold Ukrainian nationality.

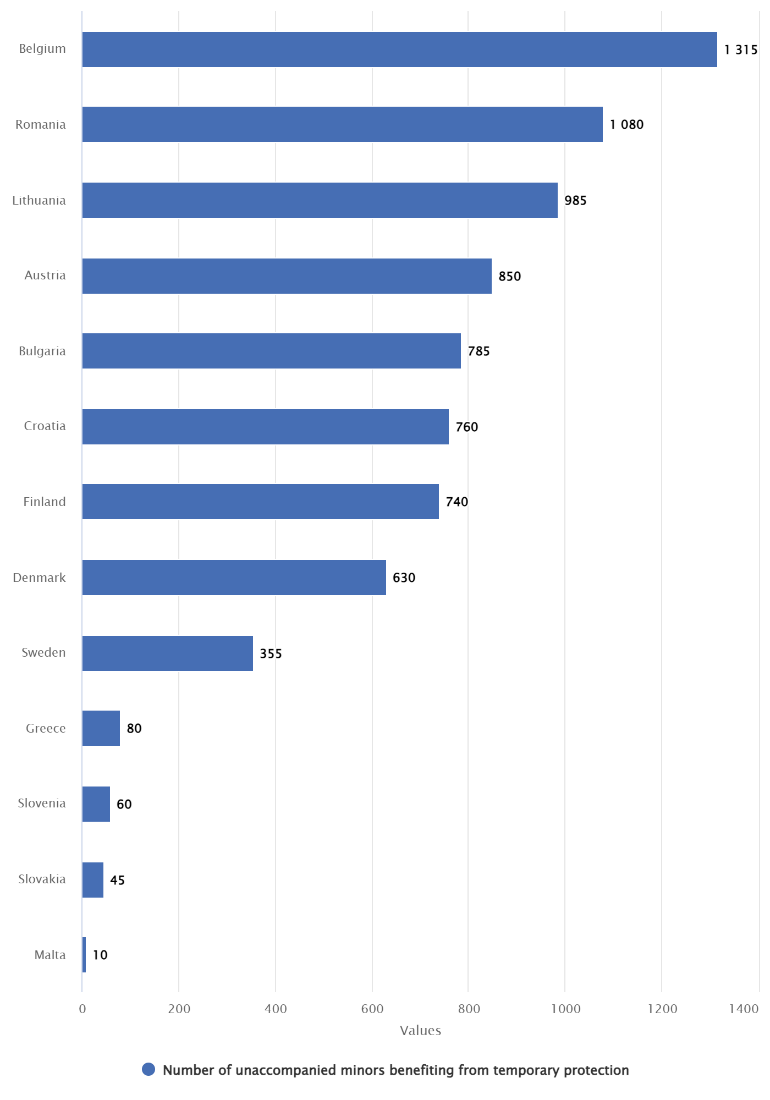

As of July 2023, 13 Member States had granted temporary protection to 7,695 unaccompanied children, according to Eurostat data. Belgium, Romania and Lithuania had the highest number of registered cases, as shown in Figure 5.

However, data FRA received indicate that other Member States received higher numbers of children than the three identified by Eurostat. Germany, Spain and Italy reported high numbers of unaccompanied children displaced from Ukraine, but do not appear in Eurostat data. See Annex 2 for a compilation of the national data reported to FRA on the number of unaccompanied children in EU Member States.

Figure 5 – Number of unaccompanied children (0 to 18 y.) beneficiaries of temporary protection, in EU Member States, as of July 2023

[End alternative ]

A horizontal bar chart shows Eurostat data for 13 Member States on the number of unaccompanied children who are beneficiaries of temporary protection as of June 2023. Numbers range from over 1,200 in Belgium to 10 in Malta.

Source:Eurostat,data extracted on 14 September 2023.

FRA’s research network, Franet, gathered data from national authorities regarding various categories of children displaced from Ukraine, including unaccompanied children. The comprehensiveness of the data varies greatly. Typically, the numbers reflect the total count of children granted temporary protection status in each Member State since March 2022.

The top five countries with the highest recorded count of unaccompanied children who fled the Ukraine and were granted temporary protection or an alternative residence status are as follows: Romania (5,008, 30 April 2023); Italy (4,706, 30 April 2023); Germany (3,891, 30 October 2022); Spain (2,000, 22 March 2023).

In Belgium, both the national Guardianship Service and the Federal Public Service for Home Affairs register unaccompanied children who fled Ukraine: the Guardianship Service indicated 1,453 unaccompanied children as of 14 June 2023 and the Federal Public Service for Home Affairs had 1,298 as of 30 April 2023.

All other EU countries have registered fewer than 1,000 unaccompanied children displaced from Ukraine, except Austria that recorded 1,105 as of 1 May.

Data updates are irregular and the recording methods differ across Member States. Some report on the number of unaccompanied children who have left. For example, Croatia recorded 528 children who arrived without parents or legal guardians since the beginning of the war, however, 381 guardianships ended, 332 for boys and 39 for girls, due to the child turning 18 or leaving Croatia. Data received by FRA, as of 4 July 2023, indicate only three unaccompanied boys remain in Croatia.[10] Croatia, Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy, email received on 4 July 2023

Slovakian data make it possible to distinguish between the total number of unaccompanied children who were registered (153) and those who, as of 30 April, are still present in the country (32 children).

The extent of breakdown and additional information varies. In Belgium, the Guardianship Service provided a detailed breakdown concerning the 1,453 unaccompanied children from Ukraine. As of 14 June 2023, data reveal that 186 children had legal guardians appointed; 78 of these guardianships were ongoing and 108 had concluded.