Member States are duty-bearers per se under the CRC. However, national, regional and local authorities share child protection responsibilities.

National governments have obligations to promote, ensure and protect children’s rights within their jurisdictions, regardless of state structure. These obligations are derived from international, European and national law.

Regional entities are responsible for promptly implementing national policies and ensuring compliance with existing laws and policies.

Local authorities can have many roles in ensuring the protection and promotion of the rights of children. They may monitor, coordinate or develop specific laws and policies, depending on the national structure.

Non-state, private and community actors also play important roles. Civil society organisations support the implementation of national policies by providing analysis and expertise. Their analysis and expertise acts as a warning mechanism and helps with the monitoring and implementation of obligations deriving from international and EU law and policies.

Cross-sectoral coordination among all relevant governmental actors and between state and non-state actors is essential for effective integrated child protection systems. This requires a national unit that is responsible for coordinating responsibilities and ensuring coordination between the decentralised entities.

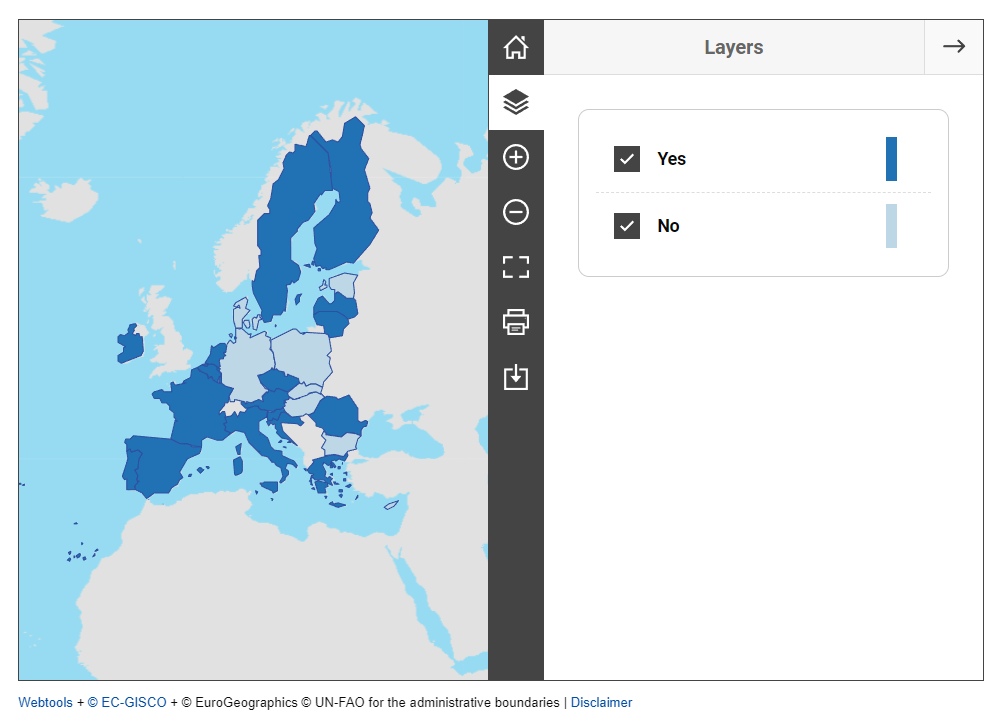

Figure 3 – Decentralised child protection responsibilities

Alternative text: A map shows that with the exception of four EU Member States, all other Member States decentralise child protection responsibilities regionally and/or locally. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Most Member States distribute child protection responsibilities among ministries and across national, regional and local authorities.

- Child protection responsibilities at national level are assigned to and/or shared among ministries of welfare, social affairs, justice and education in many Member States.

- Member States’ approaches to the decentralisation of child protection systems vary. Some Member States assign responsibilities to regional or local authorities and other bodies. For instance, child protection is a regional-level responsibility in some federal states or Member States with autonomous territories.

- National authorities maintain the right and responsibility to coordinate and set standards at national level in some Member States. In others, local or regional authorities carry full responsibility and enjoy high levels of autonomy.

Child protection responsibilities are decentralised at different levels, apart from in Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta. These three countries have established centralised authorities. Ireland has the Child and Family Agency, which reports to the Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth. Luxembourg has the National Office for Children (Office National de l’Enfance). Malta has the Child Protection Directorate and the Directorate for Alternative Care (Children and Youth).

Sweden decentralises the operation of its child protection system. However, it uses national law to supervise and regulate this.

Some Member States assign responsibilities to regional/provincial authorities: Belgium and Cyprus. Others assign them to local/municipal authorities: Bulgaria, Germany, Estonia, Portugal and Romania.

In Belgium, Spain and Austria, child protection responsibility lies at regional level. However, municipal authorities bear primary responsibility for child protection.

Regional and local authorities share responsibilities in 16 Member States: Czechia, Denmark, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland. Municipalities hold no primary responsibility for child protection.

In some Member States, there are specific directorates for child protection, such as Romania’s General Directorate of Social Assistance and Child Protection. These directorates are in charge of ensuring the implementation of social policies in the field of child protection. They also ensure implementation of policies on other people, groups or communities in need of social assistance. The directorates have a role in the administration and provision of social assistance benefits and social services.

However, these general directorates are often understaffed and underfunded. These issues prevent them from playing a significant role in ensuring the comprehensive protection of children. This is the case for Romania’s general directorate.

Other important initiatives have been introduced in several Member States. For example, the National Child Protection Service in Hungary is a unified institution responsible for the Budapest Child Protection Service and 19 regional child protection services in 19 counties. It represents the interests of children and promotes equal opportunities. The service aims to ensure regional institutions operate under the same principles and guidelines, making child protection services available to all children in all regions. It manages expert committees on child protection, hires guardians and coordinates placement activities.

In Spain, the Ministry of Social Rights and Agenda 2030, the Directorate General for Child and Adolescent Rights, the Public Ministry, the Spanish Ombudsman and the Childhood Observatory coordinate child protection policies. The Childhood Observatory plays a main role. The Childhood Observatory studies and monitors the quality of life of the child and adolescent population. It makes recommendations on public policies affecting children and adolescents.

Civil society organisations, non-state, private and community actors also play important roles. In some Member States, such as Hungary, civil society organisations are registered in tribunal courts. In Hungary, various authorities, including the National Tax and Customs Administration, the Hungarian State Audit Office and the respective court, control the organisations. Act CLXXXI of 2011 and Act V of 2013 regulate legal supervision.

The situation in Slovenia is somewhat different: agreements with civil society organisations are not in place. Slovenia’s child protection system is closely connected to the national social protection system. The national system covers measures for children, including initial social assistance, personal assistance, crime victim assistance and institutional care.

In addition, the Slovenian Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities collaborates with non-governmental organisations to publish public calls for proposals and co-financing of social protection programmes and programmes targeting families. The last public call for funding of family centre activities was published in 2020 for 2021–2025.

Effective integrated child protection requires cross-sectoral coordination between all relevant government actors and between state and non-state actors.

A national unit in charge of coordinating responsibilities promotes and ensures coordination among central government departments, various line ministries, different provinces and regions, central and other levels of government, government, civil society and private sector providers. It also contributes to effective implementation of laws and policies. Cooperation and coordination is even more vital in decentralised systems.

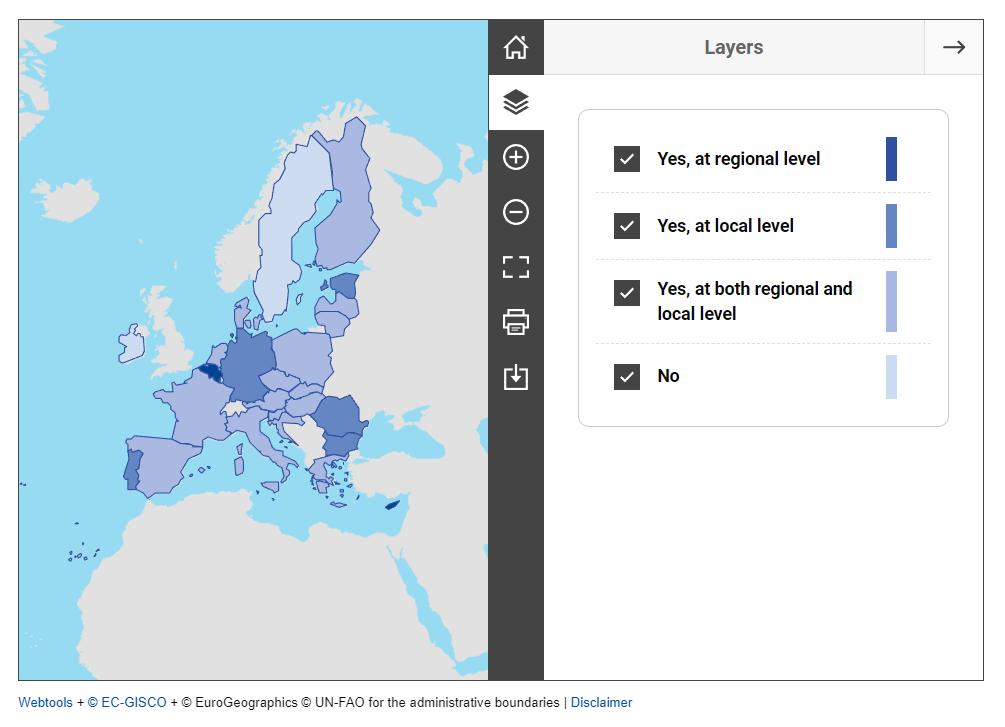

Figure 4 – Central authority with national coordinating role

Alternative text: A map shows that 13 EU Member States have established a distinct authority to coordinate and often monitor the implementation of national child protection policy and legislation. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- In principle, the ministry assigned primary responsibility for child protection has a national coordinating and monitoring role. Subordinate administrative structures, such as national authorities or departments, assume responsibility for the day-to-day tasks.

- In most EU Member States, there are mechanisms for inter-agency cooperation between actors with responsibility for child protection. However, often operational coordination is challenging because of the overlapping roles and responsibilities of actors in child protection and the failure to clearly delineate these roles and responsibilities.

Coordination responsibilities, including monitoring, lie with the ministry that primarily holds responsibility for child protection in eight Member States (see Table 4): Belgium, Czechia, Greece, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland and Sweden. Within the ministry, a specific administrative unit is typically developed for this coordination.

Thirteen Member States have established a distinct authority to coordinate and often monitor the implementation of national policy and legislation. This applies to Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Spain, Croatia, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia.

In Estonia, Greece and Croatia, there is no formal regulation of the cooperation between actors with responsibilities for child protection.

In 13 EU Member States, a single authority is responsible for monitoring data collection and centralised coordination and data sharing at national level. In addition, 10 of those Member States have a national database for collecting relevant data.

Table 4 – Authorities with coordination responsibility and/or data sharing at national level, by EU Member State

|

EU Member State |

Authorities with coordination responsibility and/or data sharing at national level |

|

Austria |

Federal Chancellery of Families and Youth (Bundesministerium für Familien und Jugend) |

|

Belgium |

National Commission on the Rights of the Child (De Nationale Commissie voor de Rechten van het Kind / La Commission nationale pour les droits de l’enfant / Die Nationale Kommission für die Rechte des Kindes) – federal level |

|

Bulgaria |

State Agency for Child Protectionhttps://sacp.government.bg/en (Държавна агенция за закрила на детето) – the National Council for Child Protection (Национален съвет за закрила на детето, НСЗД) Национален съвет за закрила на детето, НСЗД))was set up inside the agency |

|

Croatia |

Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy (Ministarstvo rada, mirovinskoga sustava, obitelji I socijalne politike) |

|

Cyprus |

Social Welfare Services (Υπηρεσίες Κοινωνικής Ευημερίας) of the Ministry of Justice and Public Order (Υπουργείο Δικαιοσύνης και Δημοσίας Τάξεως) |

|

Czechia |

Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs – Department of Family and Protection of Children’s Rights (Ministerstvo práce a sociálních věcí – Odbor rodiny a ochrany práv dětí) Ministry of Health (Ministerstvo zdravotnictví) and Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (Ministerstvo školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy) – for paedopsychiatric and infant care |

|

Denmark |

Ministry of Social Affairs, Housing and Senior Citizens (Social-, Bolig- og Ældreministeriet) |

|

Estonia |

Government of the Republic (Vabariigi Valitsus), prevention council Ministry of Social Affairs (Sotsiaalministeerium), Social Insurance Board (Sotsiaalkindlustusamet) |

|

Finland |

Department for Communities and Functional Capacity (yhteisöt ja toimintakyky -osasto / avdelningen för gemenskaper, organisationer och funktionsförmåga), subordinated to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö) |

|

France |

No leading institution at national level The Secretariat of State for Children (Secrétaire d’Etat chargé de l’Enfance), under the authority of the Prime Minister, shares the responsibility with other subentities. These include advisory bodies, the National Council for Child Protection (Conseil National de Protection de l’Enfance) and the France Protected Children Public Interest Group (Le Groupement d’Intérêt Public France Enfance Protégée). |

|

Germany |

State Child and Youth Welfare Authorities (Landesjugendämter) Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend) Federal Ministry of Justice (Bundesministerium der Justiz) |

|

Greece |

National Centre for Social Solidarity (Εθνικο Κεντρο Κοινωνικησ Αλληλεγγυησ), subordinated to the Ministry of Labour and Social Security (Υπουργείο Εργασίας και Κοινωνικής Ασφάλισης) General Secretariat of Welfare (Γενική Γραμματεία Πρόνοιας) in the Ministry of Labour and Social Security |

|

Hungary |

Ministry of Interior (Belügyminisztérium) |

|

Ireland |

Child and Family Agency (Anghníomhaireacht um Leanaí agus an Teaghlach) |

|

Italy |

National Observatory on Childhood and Adolescence (Osservatorio nazionale per l’infanzia e l’adolescenza) Several ministries have primary responsibility: Ministry for Sport and Young People (Ministro Sport e Giovani); Family Policies Department (Dipartimento per le Politiche della Famiglia); Ministry of Education and Merit (Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito); Ministry of Disabilities (Ministero per le Disabilità); Ministry of Justice (Ministero della Giustizia); Ministry of Labour and Social Policies (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali); Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell’Interno); Ministry of Health (Ministero della Salute). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale) |

|

Latvia |

Ministry of Welfare (Labklājības ministrija) |

|

Lithuania |

Ministry of Social Security and Labour (Socialinės apsaugos ir darbo ministerija) Family and Child Rights Protection Group (šeimos ir vaiko teisių apsaugos grupė), under the Ministry of Social Security and Labour State Child Rights Protection and Adoption Service (Valstybės vaiko teisių apsaugos ir įvaikinimo tarnyba) under the Ministry of Social Security and Labour |

|

Luxembourg |

Ministry of National Education, Childhood and Youth (Ministère de l’Education nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse) |

|

Malta |

Child Protection Directorate |

|

Netherlands |

Youth Authority (Jeugdautoriteit) Child Care and Protection Board (Raad voor Kinderbescherming), under the Ministry of Justice and Security (Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid) |

|

Poland |

Children’s Rights Ombudsman (Rzecznik Praw Dziecka) |

|

Portugal |

National Commission for the Promotion of the Rights and the Protection of Children and Young People (Comissão Nacional de Promoção dos Direitos e Proteção das Crianças e Jovens) |

|

Romania |

National Authority for the Protection of Children’s Rights and Adoption (Autoritatea Naţională pentru Protecţia Drepturilor Copilului şi Adopţie), subordinated to the Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Protection and Elderly Persons |

|

Slovakia |

Committee for Children and Youth (Výbor pre deti a mládež) Central Office of Labour, Social Affairs and Family (Ústredie práce, sociálnych vecí a rodiny), under the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic (Ministerstvo práce, sociálnych vecí a rodiny Slovenskej republiky) |

|

Slovenia |

Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (Ministrstvo za delo, družino, socialne zadeve in enake možnosti) |

|

Spain |

Childhood Observatory (Observatorio de la Infancia) Ministry of Social Rights and Agenda 2030 (Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030) |

|

Sweden |

Ombudsman for Children (Barnombudsmannen), under the government’s authority |

Source: Franet, 2023.

According to Article 3(3) of the CRC (emphasis added):

‘States Parties shall ensure that the institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision’.

Local authorities typically implement policy and act as the primary service provider within decentralised systems. Some outsource child protection services to the private sector and/or subcontract private actors, including civil society organisations. Nevertheless, in all decentralised systems, the government retains responsibility and capacity for ensuring that the CRC obligations are respected.

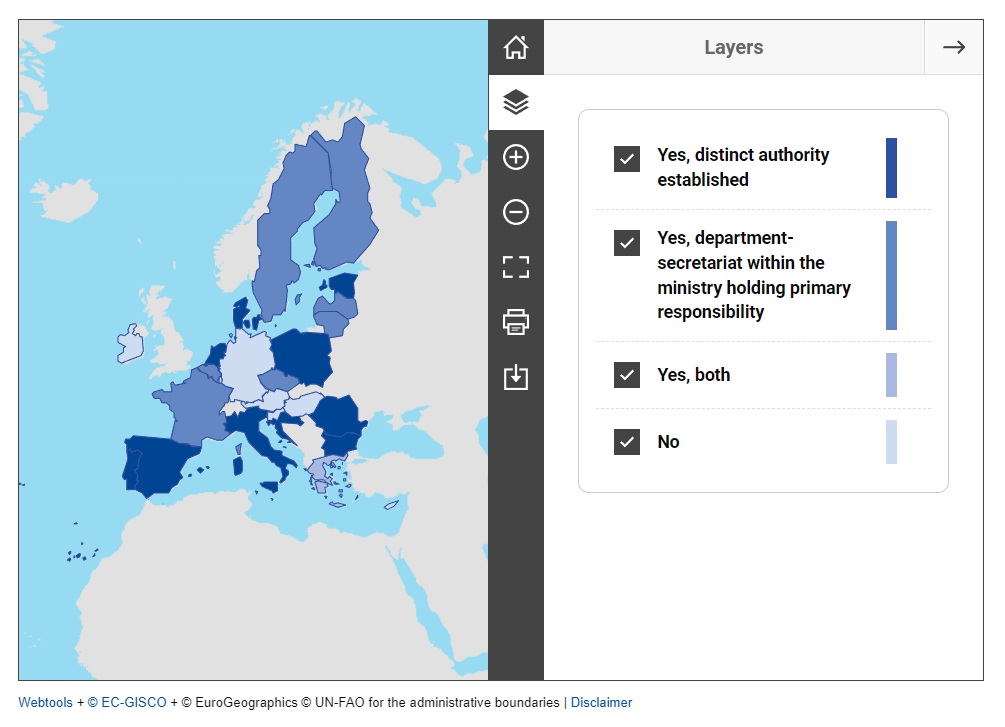

Figure 5 – National legal framework allows for subcontracting and/or outsourcing alternative care services to private providers of any nature

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not Member States’ national legal framework allows for subcontracting and/or outsourcing alternative care services to private providers. 24 Member States’ national legal framework allows for subcontracting and/or outsourcing alternative care services. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

In most Member States, the national legal framework allows national, regional and local authorities to outsource child protection services to non-state actors. These actors can be, for example, civil society organisations, private and religious institutions, and for-profit and not-for-profit associations that offer child protection services. This is the case in Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Finland and Sweden.

- Civil society organisations play an increasingly important role in this context. They provide key child protection services, such as alternative care, that traditionally only state actors offered.

- Private commercial entities offer alternative care services, such as residential and foster care, in most Member States.

- The growing involvement of the private sector can create challenges linked primarily to potential conflicts between the child’s best interests and the private sector’s profit interests. As a result, effective monitoring is essential.

- Some Member States are reinforcing cooperation between public and private entities to improve coordination between alternative care services.

- In recent years, several service providers, such as organisations or public authorities, have developed or strengthened their capacity in the area of mental health.

In 24 Member States, the national legal framework allows for subcontracting and/or outsourcing alternative care services to private/commercial institutions and companies. This is the case in Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden.

In some Member States – such as, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and Finland – private commercial entities play an important role as service providers and run a large share of the alternative care settings.

Other Member States, such as Bulgaria and Lithuania, do have legal provisions for this. However, alternative care services have up to now been subcontracted and/or outsourced only to non-profit institutions.

For example, in Croatia, several non-profit institutions provide protection for children. These institutions include the Croatian Institute for Social Work, Centre for Special Guardianship and the Family Centre. Their work covers those with disabilities, those at risk of poverty, immigrants, and victims of abuse, exploitation and violence. These institutions also assist children in court proceedings and children with addiction, behavioural problems and sanctions.

In the Netherlands, non-profit institutions such as the Municipal Centre for Youth and Families provide crucial support to children and parents. The centre operates under the Youth Law. It offers information, counselling and assistance with child development and parenting. The centre focuses on positive support, including healthcare and support for families and their children.

Equally noteworthy is the situation in Hungary. Services are offered in a multilevel manner throughout the country. For example, since 2016, family and children welfare centres have been responsible for all family and children centres in a county. The counties, in turn, are divided into districts.

The centres provide special assistance regarding key issues. For example, centres cover issues concerning child–parent contact, social work in schools and social work in hospitals. They provide experts in legal and psychological assistance and support professional child protection work in the district and county.

Church-related organisations are also involved in child protection in 10 Member States: Czechia, Denmark, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Malta, Austria, Poland, Portugal and Slovenia. Religious institutions provide, for instance, financial support, assistance of various kinds and counselling, care centres, crisis accommodation and other services. They also undertake street work.