Unaccompanied children receive some protections under international law. The Charter grants children the right to protection and care necessary for their well-being (Article 24). The CRC guarantees special protection and assistance of the State to children temporarily or permanently deprived of their family environment (Article 20.1). It requires States Parties to the Convention to take appropriate measures to ensure that a child seeking refugee status, whether unaccompanied or accompanied by their parents or by any other person, receives appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance in the enjoyment of applicable rights (Article 22).

The CRC also requires States Parties to take all appropriate measures “to promote physical and psychological recovery and social integration of a child victim of: any form of neglect, exploitation, or abuse, torture, or any other form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or armed conflicts” (Article 39).

With children comprising a third (32.8%) of the around 4 million people from Ukraine benefitting from temporary protection in the EU, child protection systems across Europe are under increased pressure. Specific situations, such as those of children traveling without parents, or the many children displaced with family friends or neighbours, require a dedicated response by child protection.

Child protection systems in the EU vary widely. FRA’s mapping on child protection, which is currently being updated, shows the fragmentation of the EU legal and policy landscape, with a wide range of approaches across Member States in the structure and operation of such systems. The European Commission has emphasised the importance of providing comprehensive services, outlining 10 principles for integrated child protection systems and is developing an initiative to encourage authorities and services to work better together, as mandated by the EU Strategy on the rights of the child.

Child protection services are often decentralised to the municipal level or provided by civil society actors that are sub-contracted. The procedures to protect unaccompanied children in some Member States are provided by international protection or migration law. In other Member States their protection is a responsibility of child protection services, no matter their legal status. Responsibilities for accommodation, representation and ongoing care are frequently shared among different Ministries. Child protection authorities are generally responsible for coordinating and monitoring the situation of children evacuated from Ukrainian institutions (see Chapter 6.1).

The need for well-coordinated child protection systems involving all relevant actors has been highlighted once more with the arrival of thousands of children from Ukraine. Coordination between child protection and migration authorities is crucial when dealing with children escaping war.

In all Member States the standard child protection system applies to children displaced from Ukraine. Policies and practices applied with other third country national children arriving unaccompanied also apply to children displaced from Ukraine. Some Member States developed policies in the first weeks and months of arrival to ensure clarity of the procedure and to strengthen the coordination of different actors.

For example, the Italian authorities introduced a plan for unaccompanied foreign children to define roles and responsibilities and ensure effective communication. An accompanying addendum further defined the policy. The plan covered the procedure for possible transfers of unaccompanied children from Ukraine to Italy. This was instrumental in preventing possible displacement, disappearance or trafficking of children.

Bulgaria has a coordination mechanism for unaccompanied and separated children that defines roles and responsibilities of child protection authorities. In practice, it is only triggered when adults travelling with the children consent to child protection measures being applied to them. In all other cases, the children remain with the adults with whom they arrived and the mechanism is not triggered.[28] Bulgaria, Social Assistance Agency (2023), Letter 04-00-0948-1/05.06.2023 to the Center for the Study of Democracy, 5 June 2023.

In addition to establishing new bodies to coordinate a national response (see Chapter 1), several Member States (Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Romania, Italy) created teams to enhance child protection for Ukrainian children.

Portugal established a multidisciplinary monitoring group comprising teams from the Ministry of Labour, Solidarity and Social Security, the Ministry of Justice, the Immigration and Borders Service and the High Commission for Migrations. Italy appointed an extraordinary commissioner for unaccompanied minors.

The Romanian government passed legislation to establish the tasks of child protection authorities both at national and local levels. In Bucharest, for example, an Emergency Ordinance created “operative groups” for unaccompanied children, at the level of each county/sector of the city’s municipality.

Several Member States planned additional human resources or training to strengthen child protection systems. Romania recruited more staff for local child protection services. In Lithuania, the State Child Rights Protection and Adoption Service prepared training in the form of online videos in Lithuanian, subtitled in Ukrainian, targeting caregivers, educators, doctors, social workers, and other organisations working with children.

Most often, the mandate of a legal guardian is to safeguard the child’s best interests and ensure their overall well-being. They should exercise legal representation complementing their limited legal capacity. The guardian should ensure that the child receives appropriate accommodation, goes to school and has access to a doctor. They should be involved in important decisions about the future of the child.

FRA’s report on guardianship systems demonstrates that despite the national legislative developments of recent years, challenges remain in the practical implementation of legal guardianship for unaccompanied children seeking asylum in Europe. There are different models of guardianship among Member States and even within Member States. There are also differences depending on the procedure that the child is involved in.

Adding to existing difficulties, the arrival of children displaced from Ukraine brought new uncertainties. Some children were displaced and arrived in Europe completely on their own, but many children arrived separately without their parents accompanied by other family members or by friends or neighbours. Thousands of children arrived within a group, evacuated from Ukrainian care institutions or foster carers.

Authorities in Member States appointed a legal representative for children that arrived on their own without any accompanying adult. They followed the same procedures as with any other third-country unaccompanied children. In some cases, the appointment was accelerated or followed slightly different procedures.

In Slovenia, under the Temporary Protection of Displaced Persons Act, an application for temporary protection must be submitted within three days. As it is not normally possible to verify the situation of the unaccompanied child within this timeframe, social work authorities are appointed as the guardian, known as the ‘special case guardian’. After the unaccompanied or separated child receives temporary protection, they assess the situation. Where the child is truly unaccompanied, they request guardianship from the court.

In the Netherlands the decentralised nature of the reception system for persons fleeing Ukraine contrasts with the regular reception system for people seeking asylum. Therefore, there was an agreement between the municipalities and guardianship authorities to coordinate and assess the child’s needs.

Latvia established a regulatory framework for children fleeing the war in Ukraine. A court responsible for orphans and custody is normally responsible for the protection of unaccompanied children. However, a new law provided for quicker procedures for finding a guardian for every child displaced from Ukraine.

In Bulgaria, guardianship arrangements can be made only for children whose parents are not known, deceased or deprived of parental rights. This does not apply to most children displaced from Ukraine. For such children, the mayor of the municipality where the child lives, appoints a guardian. This is different for asylum seeking children, who are assigned a legal representative from the legal aid register.

Thousands of children came from Ukraine without parents, but accompanied by other family members, friends or neighbour, known as separated children. Authorities in Member States assess the legality of the documents that accompanying adults may bring with them. Some accompanying adults had a letter from the parents of the child expressing their wish for the accompanying adults to take care of the child. In other instances, accompanying adults had an official notarised document granting legal responsibility to take care of the children.

As this was the first time Member States’ authorities were confronted with this situation, it initially caused confusion and resulted in some misunderstandings which some of them have been clarified since. This was also due to the initial lack of knowledge of Ukrainian law and the different forms of legal guardianship and alternative care being used in Ukraine, as highlighted by the UNICEF/Child circle report on ‘Fulfilling the rights of children without parental care displaced from Ukraine’. The European Commission also acknowledged the challenges related to unaccompanied children on arrival.

The 1996 Hague Convention on child protection became the guiding instrument in this refugee crisis. According to the 1996 Hague Convention on Child protection, official documents from Ukrainian judicial or administrative authorities should be automatically recognised in EU Member States. According to guidance from the European Judicial Network, children with habitual residence in Ukraine remain under jurisdiction of Ukrainian courts and any change of habitual residence requires the child to live in Europe for a period of time. In addition, a court must ensure that certain conditions are met.

Central authorities in each Member State, established under the Hague Convention on Child protection, have responsibility to establish the authenticity of documents in cross-border cases. However, many lack sufficient staff and resources and some national authorities are not aware of them, as highlighted by FRA’s research on child protection.

In this complex situation, the Ukrainian consulates and embassies in Member States played an important role in verifying the legitimacy of documents from Ukraine concerning the legal status of Ukrainian children fleeing the war. They supported the process of checking the authenticity of documents presented by accompanying adults and sometimes were involved in child protection decisions.

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Justice’s guidance for cases involving children stipulates that Ukrainian authorities can influence decisions about the child’s guardian, whether they are unaccompanied, accompanied by another adult, separated child or otherwise.[29] Slovakia, Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic (2022), Usmernenie Ministerstva spravodlivosti k opatrovníctvu vo vzťahu k maloletým utečencom z Ukrajiny (stav k 1.4.2023).

A bilateral agreement on legal assistance from 1983 aligns guardianship with the legal system of the other state, thereby granting the Ukrainian embassy the right to determine guardianship.[30] Slovakia, information provided by the representative of the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family via email to the Franet contractor on 5 June 2023.

In France, Ukraine’s consulate and embassy collaborated with the French authorities, aiding in cases of doubt over document authenticity is in doubt, due to the deteriorated state of some documents. In the initial stages of displacement, the consulate assisted with documentation for children and accompanying adults without the necessary legalised parental confirmation.[31] France, information provided by the representative of the Consulate of Ukraine in France via phone to the Franet contractor, 5 July 2023.

Authorities in Greece do not request prosecutors to appoint guardians for separated children if the accompanying adult has a translated and certified notarial document confirming their custody or temporary care by the parents of a separated child, according to the procedural handbook of the Special Secretariat for the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors of the Ministry of Migration and Asylum. The same applies in cases where the child entered Greece with their parents, but they are then entrusted to the care of a relative or other adult by means of a certified and translated document from the Ukrainian consulate authorities in Greece.

The automatic granting of temporary protection gave children immediate access to legal residence, education, social services, family benefits and other rights. This has significantly reduced the guardian’s tasks compared with guardians for asylum seeking unaccompanied children. The asylum procedure is a highly complex process, requiring long-term and full involvement of the child and their legal representative, and often a lawyer.

Children displaced from Ukraine normally have a valid passport. Their age does not need to be assessed, as is usually the case of other third country national children. This also implies less responsibilities for guardians.

As guardians do not need to support children through complex procedures, this has raised the question whether a guardian is necessary for children displaced from Ukraine.

For example, in the Netherlands, the child protection board considers guardianship measure to be a serious child protection measure for which there is a strict legal threshold. Guardianship is unnecessary if a parent appears to be able to make important decisions about their child over the telephone from the country of origin or a third country. On the other hand, the guardianship authority in the Netherlands, Nidos, considers it almost impossible for parents in a war situation to exercise parental authority. Exercising parental authority from a distance, in a society that is foreign to the parents and the child, is not sufficient to gain insight and assess safety and be able to make the right decisions in the child’s best interests.

According to a report by Child Circle and UNICEF, unaccompanied children need local support and assistance due to the fact that their parents are absent and not know the systems in the country. Despite their access to temporary protection, children need help navigating local procedures. A guardian may need to be appointed in line with the legal obligations. However, this does not mean that parents located in other countries do not exercise any form of parental authority. The locally appointed guardian may need to liaise with the parents in relation to certain decisions.

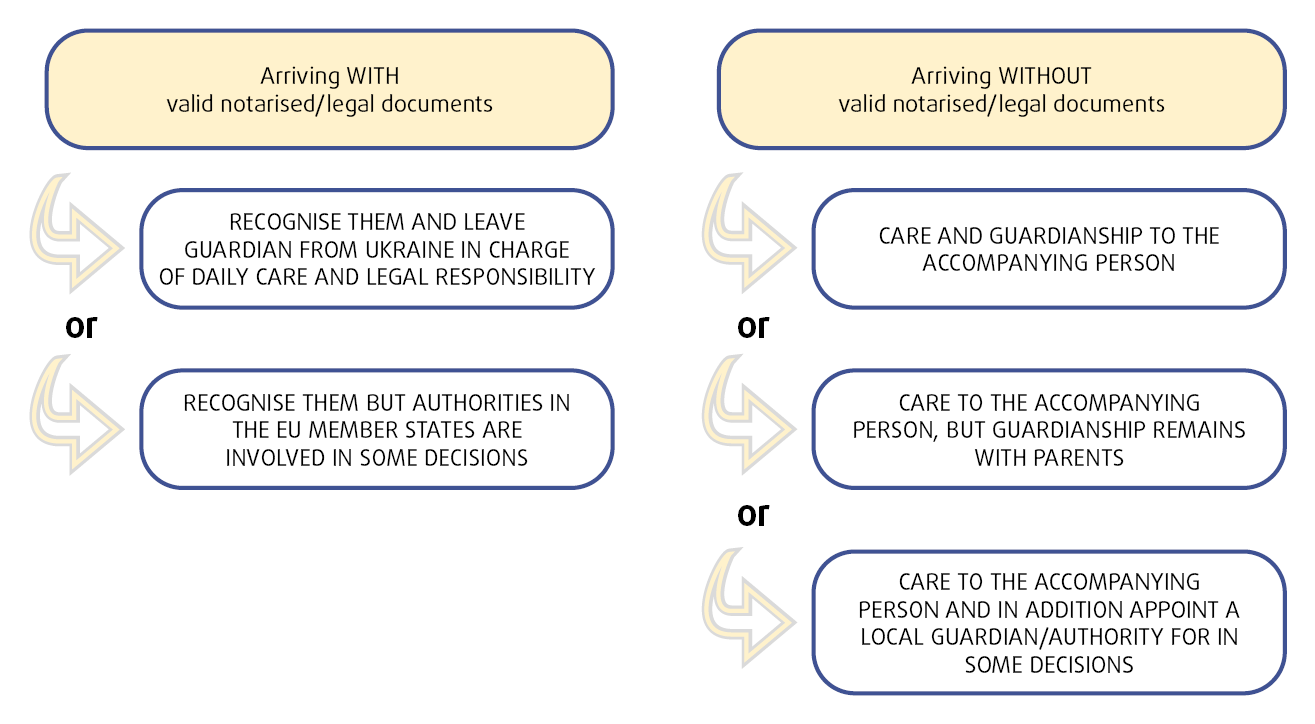

EU Member States have established different models of guardianship where responsibility is shared among different adults and organisations, as shown in Figure 6. In some jurisdictions the role of parents has been considered in the guardianship arrangement. In other jurisdictions, the responsibility for the child is also shared between the accompanying adult and the national authorities of the country of arrival. The European Commission has also suggested that developing systems for supporting Ukrainian guardians with their guardianship tasks is important.

Figure 6 – Separated children: different models of care and guardianship used in the EU Member States

A graphic outlines the different models of guardianship used in the EU Member States. The first model concerns children arriving with notarised legal documents. In such cases states either recognise them and leave the guardian from Ukraine in charge, or they recognise the guardian but national authorities are still be involved in certain decisions. The second model concerns children who arrive without valid notarised legal documents. In such cases there are three approaches: i) the accompanying person is recognised as guardian, ii) the accompanying person is recognised as caring for the child, but guardianship remains with the parents; and iii) the accompanying person is recognised as caring for the child, but legal guardian is appointed for some decisions.

Source: FRA, 2023

In Spain, the Catalonian government created a simplified process for foster care of unaccompanied Ukrainian children. Suitability assessments are conducted with families. A government entity retains legal representation and the foster family are responsible for care. The Andalucian government, adopted a law to ensure the option of ‘provisional guardianship’ for unaccompanied or separated children in addition to the role played by parents. For this arrangement, regional authorities must have the express authorisation of those who have parental authority or guardianship.

In the Netherlands, upon identifying a child, the guardianship authority Nidos meets with the child and where possible, remotely with parent. Nidos evaluates whether to seek temporary guardianship through the court. Factors considered include the child’s age, the feasibility of contact between the child and parent, the parent’s ability to exercise their authority, and the perspectives of both the child and the parent. For cases referred to Nidos temporary guardianship has not been requested, custody typically remains with the parent in Ukraine, with care provided by an adult appointed by the parent.

A similar approach was taken by the Youth Welfare Office in Berlin, Germany. Until the court appoints a guardian, the Youth Welfare Office has the right and the duty to represent the unaccompanied child. Depending on the individual case and the relationship with the parents, the family court decides whether a guardian or supplementary caretaker is necessary.[32] Germany, email by the State Youth Welfare Office for Berlin to the German Institute for Human Rights, 25 July 2022.

In Latvia, according to the Law on Assistance to Ukrainian Civilians, when the Orphan’s and Custody Court appoints the accompanying adult of an unaccompanied child as an ‘extraordinary guardian’, the living conditions of the child are inspected to ensure they care for the child in the same way as conscientious parents would care for their own child. The extraordinary guardian must notify the court of any important or noteworthy events in the life of the child, such as major injuries and accidents, rapid deteriorations of the health of the child or if the child has run away.

Similarly in Poland, the accompanying adult can be appointed as temporary guardian but will be only responsible for the day-to-day care and representation. The temporary guardian will need to obtain authorisation from the guardianship court in order to make more important decisions about the child, such as subjecting the child to an operation and leaving the country.

Several Member States received children evacuated from Ukraine who were already residing in residential care, including institutions, foster families and other types of residential or institutional care (see Chapter 6.1).

As in the case of children with an accompanying adult, but without parents, authorities in Member States had to assess legal responsibility based on the available legal documents and the relationship established between the children and the accompanying adult. Accompanying adults were typically directors or staff from the Ukrainian institution.

In the majority of cases, as with separated children, authorities in Member States automatically recognised the decision of Ukrainian authorities regarding guardianship of these children, according to the Hague 1996 Convention. This was however not always straightforward, as Ukraine had very different forms of institutional care and in most cases, children were not orphans. The report by Child Circle and UNICEF provides an overview of the different types of institutional care.

Although most of the children were not orphans, this research found no evidence of efforts to link the legal responsibility with the role of the parents. In the case of recognising the Ukrainian director or staff of the institution as legal guardians, it was their personal responsibility to liaise with parents, according to the Ukrainian legal framework.

In contrast to other countries that accepted adults accompanying children from institutions as their guardians without much difficulty, the situation in Spain differed. The Public Prosecutor’s Office in Spain issued a statement emphasising the importance of verifying accompanying adults to ensure they were legally appointed to act as such by the Ukrainian child protection system authorities. The Public Prosecutor’s Office said is not acceptable for a person who may have worked in an institution to claim that guardianship of the child, when in fact, guardianship rests with the institution itself, or the Ukrainian State.

In Belgium, Ukrainian legal guardianship was not recognised, as notary documents are not sufficient to establish legal guardianship.[33] Belgium, Interview with a project coordinator at the Guardianship Service, 14 June 2023. Also mentioned in Guardianship Service (2022), Handbook for guardians, p.27.

Although a guardian should be appointed, due to the current lack of guardians, no guardian is appointed unless the unaccompanied child is very vulnerable. Consequently, in most cases, the accompanying adult assumes the parental role. As they are not the legal representative, this can create problems whenever a legal representative is needed, such as school registration or receiving child allowances.

In a few Member States, authorities adopted a different approach. For example, according to the cooperation agreement between Lithuanian and Ukrainian authorities, children deprived of parental care arriving in Lithuania from institutional care are appointed a temporary guardian (curator) in charge of the daily care and the legal representation. In practice, the guardianship (curatorship) is established by the Lithuanian legal entities licensed to provide social care services as children’s legal representative. The staff of the Ukrainian institutions who arrive together with the children are placed with the children and are employed by the Lithuanian legal entity for the period of their stay in Lithuania.[34] Lithuania, Ministry of Social Security and Labour (2023) Reply to the request of Lithuanian Franet partner, dated 20 June 2023.

In Poland, recognition of guardians appointed for children evacuated from an institution depends on whether the care decision in Ukraine was taken by a court or by an administrative body. If the decision was taken by an administrative body, then a Polish court needs to confirm that decision. A temporary guardian who has custody of more than 15 children in Poland may apply to the county family assistance centre to employ a person to assist them, according to an amendment to the act on assistance to Ukrainian citizens in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine. The district family support centre provides legal, organisational and psychological assistance to all temporary carers and the children in their care. [35] Tymińska A. (2022), Children in foster care and unaccompanied minors from Ukraine: ex-post evaluation of the regulation and practice of application of the Ukrainian speculative law, Warsaw, 2022; Covtiuh I., Khomyn Y., Strama A. (2023), Temporary care of a minor child from Ukraine. A guide for guardians, Krakow, 2023; Association for Legal Intervention, How to become a temporary guardian of a child from Ukraine without parents, 2022.

Article 16.2 of the TPD establishes four types of living situations or accommodation, known as placements, that unaccompanied children can be offered.

Except for the latter possibility (d), that is of placing the unaccompanied child with the person who looked after the child when fleeing, the other types of placements Member States offer (a, b and c) are those established for and applied to all unaccompanied children seeking asylum in Europe.

Among the group of children fleeing the Ukraine, different types of accommodation were offered depending on whether the children travelled on their own, with relatives, friends or neighbours, or within a group.

Unaccompanied children arriving totally on their own were accommodated following the same procedures as any other unaccompanied child. In most cases, it would be a reception centre adapted for unaccompanied children. However, there was a lot of public solidarity and support for those feeling the war. Due to this wave of solidarity, many private initiatives and individuals offered accommodation. This promoted the use of foster family care in several Member States, such as Austria, Belgium, Netherlands and Spain (Catalonia).

Children fleeing Ukraine without parents, arrived with another known adult, alone or within a group. As explained in Chapter 5.3, children accompanied by a known adult, relative or friend of the family are assessed by national child protection actors. If the adult and their relationship with the child is found to be suitable, in most cases, the adult is assigned the responsibility of taking care of the child and providing accommodation. These families would then live together in family centres or private accommodation.

There were also arrivals of groups of children who were not evacuated from a Ukrainian institution or foster care (see Chapter 6.1), but were evacuated together for different reasons, for example children belonging to sport clubs.

For example, in Belgium a group of 68 children were collectively evacuated in a bilateral collaboration between the Ukrainian and Belgian governments.[36] Belgium, E-mail from the Cabinet of the State Secretary for Asylum and Migration of 22 June 2023.

Their parents had given permission for them to be accommodated in safer areas because they were temporarily unable to look after them or to travel with them. Although they were not in Ukrainian care institutions prior to leaving Ukraine, these children were placed with foster families.

Many countries reported groups of children arriving linked to sports clubs or charities. The general approach was that children should be kept together, as with the children evacuated from institutions. For example, in Croatia, around 80 children from a football academy and sailing group were accommodated in a hotel in Split, together with the adults that accompanied them upon arrival. Most of these children and adults have since returned to Ukraine.[37] Croatia, Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy, email received on 4 July 2023.

Most frequently, the coach or caregiver was appointed by the Ukrainian authorities as a legal guardian.

In Slovakia, a group of 13 children from a football team was placed in the Centre for Children and Families, as they did not want to be separated.[38] Slovakia, Information provided by the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family via e-mail communication on 5 June 2023.

IIn Hungary, the UNHCR is aware of approximately 175 children who arrived with a sport group and have since been dispersed to 10 different locations in Hungary.[39] Hungary, Information received from the UNHCR via email on 4 July 2023.

In addition to the groups arriving from sports clubs, there were also several initiatives of private actors or religious organisations involved in bringing children from Ukraine. State authorities were sometimes not informed in advance due to a lack of coordination. Consequently, there was a lack of preparation for their arrival. Often, these organisations had long-term cooperation with Ukrainian actors. These organisations typically supported summer camps or other free time activities in the EU for children affected by the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

For example, Tusla, the Irish Child and Family Agency and guardianship body became aware that an Irish organisation called Candle of Grace Charity brought 59 Ukrainian children to Dublin from Poland. The organisation previously routinely brought children from Chernobyl to visit Ireland. They responded quickly to Russian’s invasion of Ukraine. Tusla social workers conducted screening assessments and reached out to the children's parents. All the children had entered the country with their parents' knowledge and consent. Some children remain and are currently placed with host families vetted by Tusla.

Child protection authorities have an obligation to follow-up on any protection measures that have been established to ensure the child’s well-being and development. This is important to prevent risks such as children going missing or becoming victims of trafficking or abuse.

The UN guidelines on alternative care require States to ensure that all entities and individuals engaged in the provision of alternative care for children receive due authorisation from a competent authority and are subject to regular monitoring and review, as well as previous vetting. Authorities should develop appropriate criteria for assessing the professional and ethical fitness of care providers and for their accreditation, monitoring and supervision. The European Commission considers that given the circumstances of children displaced from Ukraine whose families, caregivers and guardians may change, monitoring the evolution of their situation by the national child protection authorities is necessary.

Chapter 6.2 provides an overview of how Member States are monitoring the situation of those children that were evacuated together in a group from a Ukrainian institution.

When unaccompanied children are travelling on their own and placed in reception centres, the situation of the child and of the centre will be generally monitored as established in cases for other third country national children or national children without parental care. Also, in Member States where the child is placed under the foster care programme there will be regular monitoring. For example, in Finland the Regional State Administrative Agency monitors the situation of the child and if deficiencies are found, the agency will intervene with appropriate measures.

However, unaccompanied children whose care and legal responsibility is assigned to an accompanying adult presents a more challenging situation. If the accompanying adult was assigned legal responsibility in Ukraine and that decision is recognised in the EU Member State, then it is likely that no further checks will take place from the side of child protection authorities. As in any other family setting, child protection services would only intervene if there were suspicions or reports of neglect, abuse or other situations putting the child at risk. These could be reported by teachers, doctors or other citizens.

The 1996 Hague Convention on Child Protection establishes that the country of habitual residence, is responsible for deciding protection measures. In the case of children fleeing Ukraine, the responsible state is still Ukraine. However, in urgent cases and situations of risk for the child, the state where the child is present has jurisdiction: “[the] contracting State in whose territory the child […] is present have jurisdiction to take any necessary measures of protection”, as established in Article 11.1. of the Convention.

Such a situation emerged in Portugal, where 27 Ukrainian children who had been placed with families in Portugal were then removed. The Association of Ukrainians in Portugal stated that the local Commissions for the Protection of Children and Young People had acted in accordance with the Portuguese law, which applies to any child in danger, because of ill-treatment, abandonment, abuse, lack of care, or similar situations. Following an investigation, 18 children returned to the foster families in Portugal.

In Belgium, the level of follow up and monitoring can be limited for unaccompanied children staying with relatives or other persons taking care of them. Due to a lack of local guardians and delays, the Guardianship Service can only assign a legal guardian on short notice to the most vulnerable while others are registered in a waiting list. The Guardianship Service contacts the unaccompanied children on the waiting list to check on their current whereabouts and individual situations. If this demonstrates that the child is particularly vulnerable, a guardian can be assigned on short notice. For children on the waiting list, responsibility remains with the services that are in touch with the child (such as a doctor, school or public centre for social welfare) to remain vigilant and contact child protection authorities if needed.[40] Belgium, Interview with a project coordinator of the Guardianship Service of 14 June 2023.

In situations where the care or the legal responsibility has been assigned in the Member State and is shared between the accompanying adult and the national authorities, there are more mechanisms to monitor the situation of the child. For example, in Latvia, based on the law on assistance to Ukrainian civilians, the court can inspect the living conditions and guardianship.

In Slovenia, Social Work Centres are responsible for the oversight of cases of the child being placed with the person who looked after them when they fled Ukraine. Where there is any suspicion that the child is not being adequately cared for, appropriate measures are taken to protect the rights and best interests of the child.[41] Slovenia, information was provided by the Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal opportunities upon request (email, 9 June 2023).