A legal environment conducive to an open civic space requires a strong legislative framework that protects and promotes individuals’ and organisations’ rights to freedom of association, peaceful assembly and expression in conformity with international human rights law and standards.[52] Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers (2018), Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)11 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the need to strengthen the protection and promotion of civil society space in Europe, 28 November 2018, Annex, paras. I (b) and (c).

The UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, although not legally binding, contains principles and rights that are based on human rights standards enshrined in other legally binding international instruments.

Most of these rights apply not only to the people working for CSOs but also to the CSOs themselves. They are also enshrined in the Charter, which is binding on Member States when they are acting within the scope of EU law (as provided in Article 51 (1)).[53] See, for instance, Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), C-617/10, Åklagaren v. Hans Åkerberg Fransson, 26 February 2013. For an attempt to provide guidance on cases in which national laws and practices affecting civil society space may be considered to be implementing EU law for the purpose of Article 51 (1) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, see European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL) (2020), Handbook – How to use EU law to protect civic space, The Hague, ECNL.

This may be the case when national laws or practices are implementing EU law, compromise the full implementation of EU law[54] CJEU, C-61/11 PPU, El Dridi, 28 April 2011, para. 55.

or encroach on fundamental freedoms in the EU.[55] See, for example, CJEU, C-235/17, Commission v. Hungary, 21 May 2019.

In such cases, the compatibility of national laws and practices with fundamental rights as enshrined in the Charter needs to be checked.

This chapter outlines regulatory hurdles that CSOs have encountered across the EU. Human rights CSOs and their members benefit from many human rights as enshrined for instance in the Charter, the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This includes the following rights:

- freedom of association (Article 12 EU Charter, Article 11 ECHR, 22 ICCPR);

- freedom of peaceful assembly (Article 12 EU Charter, Article 21 ICCPR, Article 11 ECHR);

- an effective remedy (Article 47 EU Charter, Article 13 ECHR, Article 2 (3) (a) ICCPR);

- a fair trial (Article 47 EU Charter, Article 6 ECHR and Article 14 ICCPR);

- property (Article 17 EU Charter, Article 1, First Protocol ECHR);

- respect for private life and correspondence (Article 7 EU Charter, Article 8 ECHR, Article 17 ICCPR);

- be protected from discrimination (Article 21 EU Charter, Article 14 ECHR, Article 1, 12th Protocol ECHR, Article 26 ICCPR).

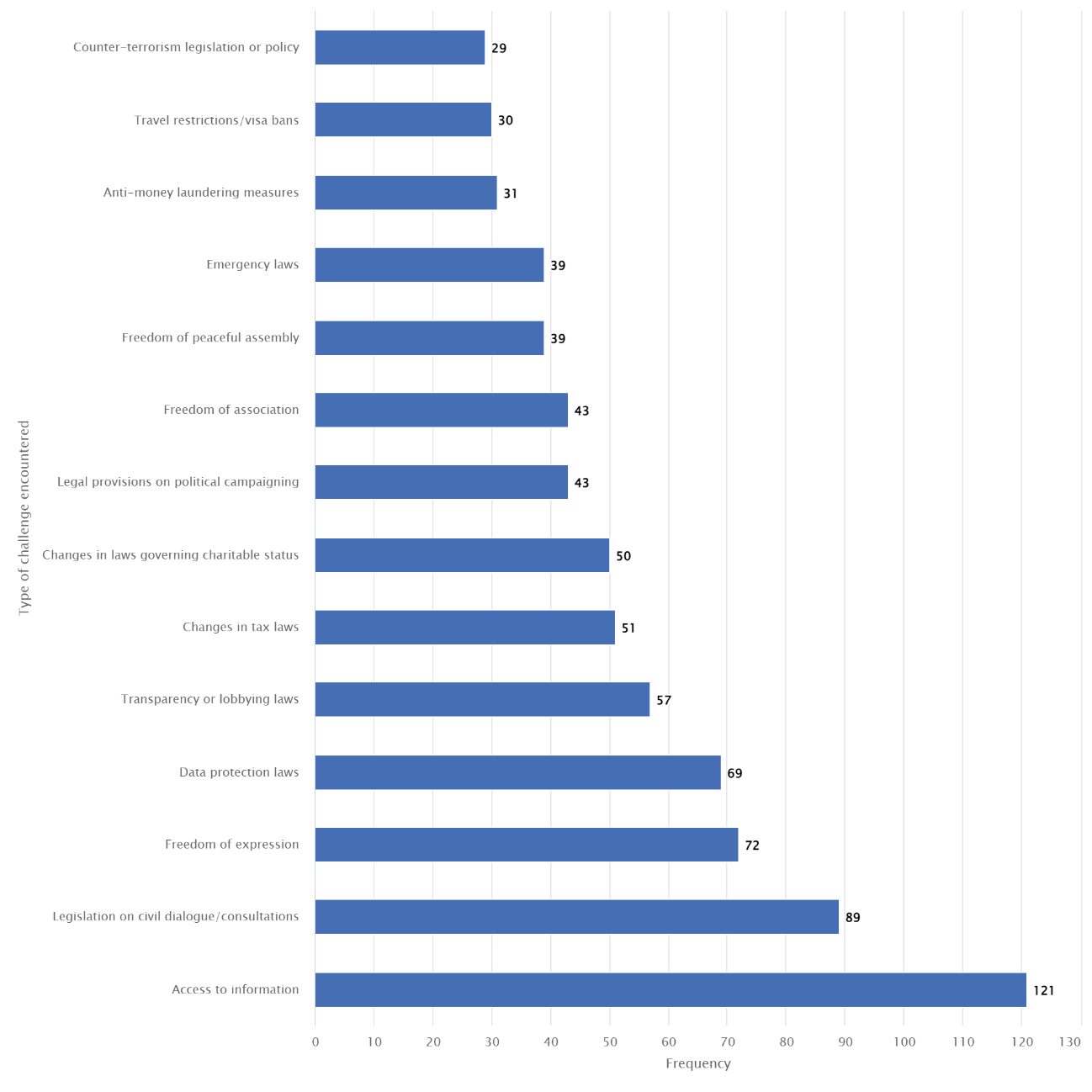

In 2022, the legal situation remained, overall, relatively unchanged from 2021, as both FRA’s consultation findings and Franet research indicate. However, a decrease in challenges related to emergency laws compared with the 2020 and 2021 consultations is visible.[56] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation and Franet’s country studies on civic space for the 27 Member States. This corresponds to the gradual lifting of emergency regulations adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The same applies to challenges linked to travel restrictions and visa bans, which posed less of a challenge in 2022.

Figure 4 shows the challenges in the legal environment that respondents to FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation face. Several areas are especially problematic: access to information, legislation on civil dialogue, the regulatory environment for political campaigning, and the lack of ability to fully exercise freedom of expression. Moreover, pressure on the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association continues in several countries.[57] Ibid.

Figure 4 – Challenges that CSOs encountered in the legal environment in the EU in 2022

The bar chart shows the different types and frequency of challenges encountered. The challenge that occurred most often was ‘Access to information’ which was encountered 121 times. The second most frequent challenge encountered was ‘Legislation on civil dialogue/consultations’ which occurred 89 times. Oter challenges encountered over 60 times were ‘Freedom of expression’, which occurred 72 times and ‘Data protection laws’ which was encountered 69 times.

Notes: Question: “In the past 12 months, has your organisation encountered difficulties in conducting its work due to legal challenges in any of the following areas? You can tick all boxes that are relevant.” N = 381.

Source: FRA’s consultation on civic space, 2022

Overly strict legal requirements for the formation and registration of associations were seen to affect freedom of association. Organisations also faced challenges when establishing their activities and conducting their work.[58] Ibid.

These include measures regarding data protection, transparency, anti-money laundering and tax.[59] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation.

In Bulgaria and the Netherlands, CSOs criticised draft laws that imposed administrative obligations on CSOs funded from abroad as overly restrictive.[60] For the Netherlands, see Dutch Section of the International Commission of Jurists (NJCM) (2022), Contribution of the Dutch Section of the International Commission of Jurists (NJCM) and other stakeholders to the fourth universal periodic review of the Kingdom of Netherlands, Leiden, the Netherlands, NJCM; the Netherlands, Minister for Legal Protection (Minister voor Rechtsbescherming) (2020), Bill for Transparency Civil Society Organisations Act (Wetsvoorstel Wet transparantie maatschappelijke organisaties), 20 November 2020, and the amendment following the opening of a public consultation: The Netherlands, Minister for Legal Protection (Minister voor Rechtsbescherming) (2021), Memorandum of amendment: Draft Bill for Transparency Civil Society Organisations Act (Nota van wijziging: Concept Wetsvoorstel transparantie maatschappelijke organisaties). For Bulgaria, see Bulgaria, National Assembly (Народно събрание) (2022), Draft Registration of Foreign Agents Act Bills (Законопроект за регистрация на чуждестранните агенти), 27 October 2022; Bulgaria, National Assembly (Народно събрание) (2022), Opinion of Civic Organisations on the Draft Registration of Foreign Agents Act (Становище на граждански организации относно Законопроект за регистрация на чуждестранните агенти), 22 December 2022.

Compliance requirements and other obstacles continued to be a challenge for NGOs in various Member States.

In Cyprus, CSOs alleged that national laws[61] Cyprus, Directive on the prevention and combating of money laundering (Register of beneficiaries of associations, foundations, federations or associations, charitable foundations and non-governmental organisations with legal personality in another state) (Οδηγία για την Παρεμπόδιση και Καταπολέμηση της Νομιμοποίησης Εσόδων από Παράνομες Δραστηριότητες (Μητρώο Πραγματικών Δικαιούχων Σωματείων, Ιδρυμάτων, Ομοσπονδιών ή Ενώσεων, Αγαθοεργών Ιδρυμάτων και μη κυβερνητικών Οργανισμών με νομική προσωπικότητα σε άλλο κράτος)).

disproportionately implementing the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive[62] Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Directive 2005/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directive 2006/70/EC, OJ 2015 L 141.

led to the suspension and closure of accounts and the blocking of funds.[63] Franet’s consultation with Civil Society Advocates and the NGO Support Centre, 10 January 2022.

In Hungary, CSOs reported that they were being asked to submit large amounts of data as part of an audit planned for in a new law[64] Hungary, Act XLIX of 2021 on the transparency of civil organisations capable of influencing public life (2021. évi XLIX. törvény a közélet befolyásolására alkalmas tevékenységet végző civil szervezetek átláthatóságáról).

on the transparency of CSOs.[65] Information from the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, provided to Franet during a telephone interview, 4 January 2023. See also Hungarian Helsinki Committee: Five Years and Counting: Government Attacks against Civil Society 2018-2023, p. 12.

The State Audit Office assists CSOs by providing voluntary tests for CSOs to evaluate their accounting systems. Civil society centres in every county and in the capital provide free advice to help CSOs operate properly. [66] Information provided to FRA by the Government of Hungary, 2023.

In Romania, CSOs criticised a new law restricting the right of CSOs to challenge building permits and comment on urban planning documents by shortening various deadlines for receiving input.[67] Romanian Senate (Senatul României), Legislative proposal amending the Law No. 50/1991 on authorizing construction works and other normative acts, to amend and supplement Law No. 350/2001 on territorial development and urban planning and to amend and supplement Administrative Litigation Law No. 554/2004 (Propunere legislativă pentru modificarea și completarea Legii nr.50/1991 privind autorizarea executării lucrărilor de construcții, pentru modificarea și completarea Legii nr.350/2001 privind amenajarea teritoriului și urbanismului și pentru modificarea și completarea Legii contenciosului administrativ nr.554/2004), November 2022; Group NGOs for Citizen (2022), ‘Parlamentul României manifestă tendințe iliberale – Dreptul ONG-urilor la litigare strategică limitat drastic’, 29 November 2022.

CSOs also expressed their concern that a new law on cybersecurity, requiring security incidents to be reported within 48 hours and the storage of large amounts of data for a long time, and imposing high fines, could also apply to watchdog NGOs and journalists due to its broad scope.[68] Chamber of Deputies (Camera Deputaților), Draft Law on cybersecurity and defence and for the modification and completion of some normative acts (Proiect de Lege privind securitatea şi apărarea cibernetică a României precum şi pentru modificarea şi completarea unor acte normative), December 2022; Association for Technology and Internet (2022), ‘Securitatea cibernetica pe masa Guvernului: cetățenii și persoanele juridice, și sub papucul serviciilor, și cu banii luați’, 8 December 2022. See also Romania, Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania – Helsinki Committee (2022), ‘Moș Parlament vine cu amenzi uriașe și pușcărie pentru cine amenință cu vorba securitatea cibernetică a statului’, 21 December 2022.

In France, CSOs protested against the requirement to sign ‘republican commitment contracts’ to obtain state approval, receive a public subsidy or host a young person performing civic service.[69] France, Law No. 2021-1109 strengthening the respect of the principles of the Republic (Loi No. 1109-1109confortant le respect des principes de la République), 24 August 2021.

They argued that this violates their right to freedom of association due to a lack of clarity in the contracts, their overly broad scope and the lack of clear remedies for breaches.[70] France, Le Movement associatif, ‘Republican commitment contract: The disagreement of associations’ (‘Contrat d’engagement républicain : le désaccord des associations’), press release, 3 January 2022.

In some Member States, measures were taken to facilitate CSOs’ enjoyment of their right to freedom of association. In Finland, the legislature passed an amendment to the Associations Act. It allows associations to hold exclusively virtual meetings, including also general meetings of members of an association , of its executive committees. This enables decisions to be made without the physical presence of (prospective) members.[71] Finland, Act amending the Associations Act (Laki yhdistyslain muuttamisesta), 8 July 2022.

In Latvia, a new accounting law allows volunteers to perform accounting functions in associations and foundations, and smaller organisations to have simplified accounting processes.[72] Latvia, Saeima, Accounting Law (Grāmatvedības likums), 10 June 2021.

Hampered access to information, the criminalisation of expression, the removal of online content, online and offline verbal harassment, censorship and defamation challenge freedom of expression. Access to information was the most common challenge in the legal environment for CSOs in 2022, FRA’s civic space consultation shows (see Figure 4). National provisions grant access to public documents. However, these provisions include broad exceptions, potentially impeding the proper exercise of this right.

In Malta, the Institute of Maltese Journalists criticised the lack of action on the recommendations of the public inquiry into the assassination of the journalist Caruana Galizia and proposed anti-SLAPP legislation.[73] Institute of Maltese Journalists, letter to Prime Minister Robert Abela, 10 October 2022.

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights also expressed concern,[74] Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, letter to Prime Minister Robert Abela, 23 September 2022.

and the Prime Minister agreed to freeze the bills based on the recommendations and scheduled a new public consultation for February 2023.[75] Institute of Maltese Journalists, letter to Prime Minister Robert Abela, 10 October 2022.

NGOs and the Commissioner for Human Rights also noted difficulties in implementing freedom of information legislation.[76] International Press Institute (2022), ‘Joint statement in support of The Shift News as it faces a freedom of information battle with the Government of Malta’, 8 August 2022; Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights (2022), Report following her visit to Malta from 11 to 16 October 2021, 15 February 2022, p. 11; Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom (2022), Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2021 – Country report: Malta, Fiesole, Italy, European University Institute, p. 12.

The Maltese Government published a number of bills which aim to further strengthen the journalistic profession. These bills were sent to the Committee of Experts on Media for their feedback and were subsequently, tabled in the House of Representatives. Although the public consultation on these bills had already take place, the Institute of Maltese Journalists requested more time for the consultation and to share their views with the government. The government abided by this request and entrusted the Committee of Experts on Media to broaden its public consultation. Currently, there is an ongoing evaluation of the Committee’s final report after which the legislative process continues. [77] Information provided to FRA by the Government of Malta, 2023.

In Sweden, legislative and constitutional amendments on the criminalisation of foreign espionage, which include bans on disclosing secret information, may hamper investigative journalism.[78] Sweden, Swedish parliament (Riksdagen) (2022), ‘Foreign espionage to be criminalised and introduced as an offence against the freedom of the press and the freedom of expression’, 16 November 2022.

In Greece, grave concerns were expressed regarding the use of spyware to monitor the activities of journalists and politicians and alleged SLAPPs against journalists trying to cover stories about spyware (for information on SLAPPs, see Section 2.2).[79] See Leontopoulos, N. and Chondrogiannos, T. (2023), ‘Interceptions: A year of investigation by Reporters United’ (‘Υποκλοπές: Ένας χρόνος έρευνας από το Reporters United’), 4 January 2023, in which the timeline of the scandal commonly referred to as ‘Predatorgate’ can be found (in Greek). International news outlets, including the New York Times (see Markham, L. and Emmanouilidou, L. (2022), ‘How free is the press in the birthplace of democracy?’, 28 November 2022) and Politico (Stamouli, N. (2023), ‘Greece’s spyware scandal expands further’, 16 January 2023) have widely reported the scandal; for more information, see Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE), ‘The European SLAPP Contest 2022’, 20 October 2022.

On 27 July 2022, a Task Force was created. It is formed my members of various relevant stakeholders, convenes once a month to discuss various topic and come up with initiatives to protect and empower journalists [80] European Commission (2023), ‘2023 Rule of Law Report: Comunication and country chapters’, 5 July 2023.

.

Improvements are also noted. The Freedom of Information Act in Slovakia was amended to comply with the EU Open Data Directive,[81] Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information (recast), OJ 2019 L 172.

expanding the range of entities covered to include more public bodies and insurance companies and specifying some terms in more detail.[82] Slovakia, Act No. 211/2000 on free access to information as amended (Zákon č. 211/2000 Z.z. o slobodnom prístupe k informáciám, 17 May 2020; Slovakia, National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada SR (2022), ‘Government Bill amending Act No. 211/2000 Coll. on free access to information and on amending and supplementing certain acts (Freedom of Information Act), as amended’ (Vládny návrh zákona, ktorým sa mení a dopĺňa zákon č. 211/2000 Z. z. o slobodnom prístupe k informáciám a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov (zákon o slobode informácií) v znení neskorších predpisov, 21 June 2022; Slovakia, National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada SR) (2022), ‘Proposal of the Group of Deputies of the National Council of the Slovak Republic for an Act amending Act No. 211/2000 Coll. on Free Access to Information and on Amendments and Additions to Certain Acts (Act on Freedom of Information), as amended’ (Návrh skupiny poslancov Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky na vydanie zákona, ktorým sa mení a dopĺňa zákon č. 211/2000 Z. z. o slobodnom prístupe k informáciám a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov (zákon o slobode informácií) v znení neskorších predpisov), 8 November 2022.

The transposition of the Whistleblower Directive progressed with the proposal and/or adoption of laws in a number of Member States. CSOs in Germany agreed on their own policy to deal with whistleblowers in the civil society sector, seeking to lead by example.[83] Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte (2022), ‘A whistle-blowing policy for civil society’ (‘Eine Whistleblowing Policy für die Zivilgesellschaft’), 30 November 2022.

In relation to freedom of peaceful assembly, climate activist-related issues became the centre of attention, superseding COVID-19-related incidents. However, there were still a few cases of the latter. The Estonian Supreme Court justified COVID-19 restrictions on freedom of assembly and other fundamental rights[84] Estonia, Communicable Diseases Prevention and Control Act (Nakkushaiguste ennetamise ja tõrje seadus), 12 February 2003, Articles 27 (3) and 28 (2), (5), (6) and (8).

on the ground of protecting life and health.[85] Estonia, Supreme Court (Riigikohus), Case 5-22-4, 31 October 2022.

In Cyprus, a demonstration against the full ban on all street protests to limit the spread of COVID-19 resulted in riot charges being brought against 11 participants, who also alleged that the police used excessive force.[86] Franet’s telephone consultation with the lawyer of the accused people, 10 January 2023; Amnesty International (2021), ‘Cyprus: Serious allegations of police abuse must be investigated and blanket ban on assemblies lifted’, 24 February 2021.

Amid growing public concern about global warming, courts continued to deal with various forms of climate protests using tactics that violated laws, including, in particular, traffic laws. For example, in May 2022, 110 climate activists were detained in Denmark for occupying bridges in Copenhagen near the parliament and government buildings. They were released after being interrogated.[87] Denmark, Civicus Monitor (2022), ‘110 activist arrested during two days of climate demonstrations’, 13 June 2022; Denmark, TV2 (2022), ‘Many deprivations of liberty at climate demonstrations – well-known author among them’ (‘Mange frihedsberøvelser ved klimademonstrationer – kendt forfatter er iblandt’), 6 May 2022.

In Germany, courts punished climate activists for setting up roadblocks and blockades at airports using a variety of criminal laws, amid calls for harsher punishment for their actions.[88]Franet [German Institute for Human Rights] (2022), An update on developments regarding civic space in the EU and an overview of the possibilities for human rights defenders to enter EU territory - Germany ; Greenpeace (2022), ‘Statement on the criminalisation of climate protests’; 14 November 2022; Reuters, ‘Climate activists glue themselves to airport tarmac in Berlin and Munich’, 8 December 2022; The Guardian, ‘Climate activists throw mashed potatoes at Monet work in Germany’, 23 October 2022.), 14 November 2022; Reuters, ‘Climate activists glue themselves to airport tarmac in Berlin and Munich’, 8 December 2022; The Guardian, ‘Climate activists throw mashed potatoes at Monet work in Germany’, 23 October 2022.

Climate CSOs called for the discussion of climate change rather than the punishment of civil disobedience.[89] Greenpeace (2022), ‘Statement on the criminalisation of climate protests’ (‘Erklärung zur Debatte um die Kriminalisierung von Klimaprotesten’), 14 November 2022.

Climate activists were fined in Portugal for disobedience because they refused to end their occupation of high schools and higher education facilities.[90] Observador (2022), ‘Young climate activists disappointed with sentence’ (‘Jovens ativistas pelo clima desiludidos com sentença’), 16 December 2022.

The Director of the Public Security Police noted that the demonstrations were dealt with in a proportionate and peaceful manner, and the interior ministry noted the importance of young people fighting for their causes.[91] Diário de Notícias (2022), ‘PSP director highlights correct behaviour of young climate activists’ (‘Diretor da PSP destaca comportamento correto dos jovens ativistas pelo clima’), 16 December 2022.

In a trade union case that could also affect climate protests in Belgium, the Court of Cassation ruled that protestors’ criminal liability for participating in a roadblock on a highway was not excluded based on their right to freedom of expression or freedom of peaceful assembly.[92] Court of Cassation of Belgium, Judgment No. P.21.1500.F (Arrêt N° P.21.1500.F), 23 March 2022; see also RTBF (2022), ‘’Blockade of the Cheratte viaduct and Court of Cassation: the appeals of the 17 convicted FGTB activists rejected’ (Blocage du viaduc de Cheratte et Cour de cassation : les pourvois des 17 militants de la FGTB condamnés rejetés, 4 April 2022.

Previously, the law had stated that only the organisers of illegal roadblocks would be punished, but the court ruled that participating in such roadblocks was also a criminal offence.[93] Liga Voor Mensenchten (2022), ‘Het Belgische stakingsrecht onder vuur’, 24 October 2022.

More general problems related to excessive restrictions on peaceful assembly persisted in some Member States. In Greece, an action plan was adopted in 2021 that emphasises the proportionate use of police powers. Nevertheless, there are some reports in the media and among CSOs of the police using excessive force, and allegations of arbitrary arrest.[94] Franet [Centre for European Constitutional Law in cooperation with Hellenic League for Human Rights and Antigone-Information and Documentation Centre on racism, ecology, peace and non-violence] (2022), An update on developments regarding civic space in the EU and an overview of the possibilities for human rights defenders to enter EU territory - Greece ; Amnesty International (2022), ‘Protect the protest! Why we must save our right to protest’, 19 July 2022.

In the Netherlands, a report by the national section of Amnesty International called for changes in both laws on and attitudes towards public protests, criticising local authorities’ excessive bans or curbs on peaceful assemblies, and many rapid arrests by police at demonstrations.[95] Amnesty International Netherlands (2022), Right to demonstrate under pressure – Rules and practice in Netherlands must improve (Demonstratierecht onder druk. Regels en praktijk moeten beter).

In Spain, CSOs criticised excessive restrictions on freedom of peaceful assembly contained in the Citizen’s Security Law.[96] Spain, Organic Law 4/2015 on the protection of public safety (Ley Orgánica 4/2015 de protección de la seguridad ciudadana), 30 March 2015.

However, they remained in force[97] Civicus (2022), ‘Citizens’ Security Law under reform: Rule of Law in Spain at stake’, press release, 11 February 2022; Amnistía Internacional (2022), The Right to protest in Spain: Seven years, seven gags that restrict and weaken the right to peacefully protest in Spain (Derecho a la protesta en España – «Siete años, siete mordazas que restringen y debilitan el derecho a la protesta pacífica en España», Madrid, Amnistía Internacional; Amnistía Internacional (2022), ’, press release, 3 November 2022.

in spite of the government’s promises to repeal them.[98] Araque Conde, P. (2022), ‘Así va la reforma de la “ley mordaza”, uno de los principales deberes pendientes del Gobierno para 2023’, 31 December 2022; Frías, C. (2022), ‘La reforma de la “ley mordaza” avanza: difundir imágenes de policías no será delito y se despenaliza el “top manta”’, 22 December 2022; Galvalizi, D. (2023), ‘La reforma de la ley Mordaza, la promesa más difícil de cumplir’, 1 January 2023; López-Fonseca, O. (2022), ‘La reforma de la “ley mordaza” reinicia el trámite parlamentario con significativas discrepancias entre el PSOE y sus socios’, 16 December 2022.

The issue of SLAPPs has gained more prominence since the European Commission proposed a directive and adopted a recommendation on SLAPPs in April 2022.[99] European Commission (2022), Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on protecting persons who engage in public participation from manifestly unfounded or abusive court proceedings (‘Strategic lawsuits against public participation’), COM(2022) 177 final, Brussels, 27 April 2022; and Commission Recommendation (EU) 2022/758 of 27 April 2022 on protecting journalists and human rights defenders who engage in public participation from manifestly unfounded or abusive court proceedings (‘Strategic lawsuits against public participation’)Recommendation (C(2022) 2428 final)

Coined in 1996,[100] Pring, G. W. and Canan, P. (1996), SLAPPs: Getting sued for speaking out, Philadelphia, PA, Temple University Press.

the term “generally refers to a civil lawsuit filed by a corporation against non-government individuals or organizations (NGOs) on a substantive issue of some political interest or social significance” aiming to “shut down critical speech by intimidating critics into silence and draining their resources”.[101] UN, Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, ‘SLAPPs and FoAA rights’.

There have been many calls for action on SLAPPs in recent years, including from the Council of Europe, the European Parliament and civil society.[102] Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (2020), ‘Time to take action against SLAPPs’, 27 October 2020; European Parliament (2021), Resolution of 11 November 2021 on strengthening democracy and media freedom and pluralism in the EU: the undue use of actions under civil and criminal law to silence journalists, NGOs and civil society, P9_TA(2021)0451, Brussels, 11 November 2021; Ravo, L., Borg-Barthet, J. and Kramer, X. (2020), Protecting public watchdogs across the EU: A proposal for an EU anti-SLAPP law.

The proposed EU directive on SLAPPs states that human rights defenders “play an important role in European democracies, especially in upholding fundamental rights, democratic values, social inclusion, environmental protection and the rule of law”. The proposal points out that they should be able to participate actively in public life and make their voices heard on policy matters and in decision-making processes “without fear of intimidation”.[103] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2022/758 of 27 April 2022 on protecting journalists and human rights defenders who engage in public participation from manifestly unfounded or abusive court proceedings (‘Strategic lawsuits against public participation’).

For reasons related to EU competence, the legislative proposal covers only cross-border civil cases. Purely national cases are dealt with through an accompanying, non-binding recommendation for the Member States.[104] Ibid.

Negotiations at EU level will clarify the exact scope of the legislation, including the definition of abusive court proceedings, the definition of a cross-border case, and the procedures for early dismissal (the proposal allows courts and tribunals to dismiss cases that are manifestly unfounded) and the protection of SLAPPs victims (including through the provision of legal aid).

Evidence indicates the persisting need for action to curb SLAPPs, especially because, as the proposal notes, none of the Member States currently have any such protection in place. A 2022 Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe report identifies 570 SLAPPs cases filed in over 30 European jurisdictions from 2010 to 2021.[105] CASE (2022), Shutting out criticism: How SLAPPS threaten European democracy, Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, Greenpeace International and Amsterdam Law Clinics. See also CASE (2023), ‘How SLAPPs increasingly threaten democracy in Europe – New CASE report’, 23 August 2023.

This is despite State obligations to facilitate the freedom of expression and association under the Charter (Articles 11 & 12), the ECHR (Articles 10 & 11) and ICCPR (Articles 19 & 22).[106] UUN, Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, ‘SLAPPs and FoAA rights’, pp. 3-5.

Additional cases included the lawsuits in Poland that local government entities filed against an LGBTIQ+ activist for calling out ‘LGBT-free zones’, which the courts dismissed. In Austria, the municipality of Vienna has threatened to claim back costs from environmental activists who blocked the construction of a tunnel. Construction of the tunnel was abandoned after protests from various individuals and organisations.[107] Bolanowski, R. (2022), ’Bart Staszewski wins in court against the municipality of Niebylec. They demanded an apology in the pages of the New York Times and the Guardian‘ (Bart Staszewski wygrywa w sądzie z gminą Niebylec. Żądali przeprosin na łamach "New York Timesa" i "Guardiana"), 5 May 2022; Ambroziak, A. (2022), Atlas of Hate activists win against Ordo Luris and homophobic local government (‘Aktywiści Atlasu Nienawiści wygrywają z Ordo Iuris i homofobicznym samorządem’), 21 December 2022; Austria, Federal Ministry of Climate Protection, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology (2021), Evaluation of the construction program Future in implementation of government program - Conclusions, GZ. 2021-0.747.473 (Evaluierung des Bauprogramms der Zukunft in Umsetzung des Regierungsprogramms – Schlussfolgerungen, GZ. 2021-0.747.473), Vienna, Federal Ministry of Climate Protection, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology; ORF Wien (2021), City withdraws threat of legal action against minors - wien.ORF.at (Stadt zieht Klagsdrohung an Minderjährige zurück), 23 December 2021; Amnesty International Austria, ‘The climate protection and human rights movement as well as scientists condemn the city of Vienna’s threats to sue as human rights violations’ (Klimaschutz- und Menschenrechtsbewegung sowie Wissenschaftlerin verurteilen Klagsdrohungen der Stadt Wien als Menschenrechtsverletzung), 15 December 2021; Kleine Zeitung (2022), ‘SLAPP lawsuits: freedom of expression is threatened’(SLAPP-Klagen: Die Meinungsfreiheit ist bedroht), 18 February 2022; MeinBezirk.at (2022), ‘City of Vienna refrains from taking legal action against Lobau activists’(Stadt Wien verzichtet auf Klagen gegen Lobau-Aktivisten)’, 15 February 2022.

In Croatia, a hotel company filed a lawsuit against activists who had spoken out against the construction of a luxury hotel, citing damage to the company’s image.[108] Croatia, Glas Istre (2022), ‘The investor sued three citizens from the Lungomare Initiative. They are now asking the people of Pula to donate money for court costs’ (‘Investitor tužio troje građana iz Inicijative za Lungomare. Oni sada traže od Puležana da im doniraju novac za sudske troškove’), 23 November 2022; Croatia, Novi list (2022), ‘Sued members of the referendum initiative for Lungomare collected HRK 25,000’ (‘Tuženi članovi referendumske inicijative za Lungomare skupili 25 tisuća kuna’), 26 November 2022; Croatia, Lupiga (2022), ‘Activists are filled with lawsuits: “This is like a fight between David and Goliath”’ (‘Aktivisti zasuti tužbama: “Ovo je kao borba Davida protiv Golijata”’), 24 November 2022.

This triggered activists’ plans to raise money internationally to defend other activists against SLAPPs.[109] Croatia, Glas Istre (2022), ‘The investor sued three citizens from the Lungomare Initiative. They are now asking the people of Pula to donate money for court costs’ (‘Investitor tužio troje građana iz Inicijative za Lungomare. Oni sada traže od Puležana da im doniraju novac za sudske troškove’), 27 November 2022.

In Slovenia, the Ministry of the Interior ordered protesters and activists to cover the costs of policing unsanctioned events.[110] Amnesty International (2022), ‘Slovenia: Withdraw claims for protesters to cover costs associated with policing assemblies’, press release, 16 March 2022.

The ministry under the new government revoked this decision. The parliament recently adopted the Act regulating issues related to specific minor offences during CVOID-19, addressing minor offence proceedings that lacked a lawful or constitutional basis. It provides for suspension of ongoing minor offence proceedings, reimbursement of fines and costs of proceedings paid, and an automatic deletion of data from minor offence records. [111] ) Slovenia, Ministry of Justice (2023), ‘Act regulating issues relating to specific minor offences during covid-19 adopted by the National Assembly’ (‘Zakon o ureditvi vprašanj v zvezi z določenimi prekrški v času covid-19 sprejet v Državnem zboru’), 20 September 2023.

A number of criminal cases were also opened, by either bringing charges or summoning individuals to police stations. Although the cases were not technically SLAPPs, they were allegedly aimed at stifling human rights activity. They included a criminal law (and trademark) case against an environmental activist in Italy, who faced a lawsuit from the regional government for using the term ‘Pestizidtirol’ (Pesticide Tyrol) instead of ‘Südtirol’ (South Tyrol). In another, the police summoned a Bulgarian journalist to reveal her sources about the affairs of a political party.[112] CASE (2022) ‘Pesticide SLAPP in Südtirol/Alto Adige ends in victory for freedom of expression’, 6 May 2022; Bulgaria, Association of European Journalists (Асоциация на европейските журналисти – България) (2022), ‘The government's unacceptable pressure on journalists to reveal the sources of journalistic investigation continues’ (’Продължава недопустимият натиск на властта за разкриване на източниците на журналистическо разследване’), press release, 16 September 2022.

Cases can also be brought to both civil and criminal courts, for example as happened to a Croatian activist group that had spoken out against the planned construction of a golf resort near Dubrovnik.[113] Croatia, Human Rights House Zagreb (Kuća ljudskih prava Zagreb), Human rights defenders in Croatia – Challenges and obstacles (Branitelji ljudskih prava – izazovi i prepreke), Zagreb, Human Rights House Zagreb.

The combination of criminal and civil cases brought against them resulted in legal costs, the loss of time to conduct their activities and a more negative perception of the group in society.