Fundamental rights considerations: NGO ships involved in search and rescue in the Mediterranean and criminal investigations - 2018

Legal actions against NGOs and volunteers involved in search and rescue at sea based on domestic criminal or administrative law must be implemented in accordance with the relevant international, Council of Europe and EU fundamental rights law and refugee law standards. This requires making the delicate distinctions between real smugglers and those enforcing the human rights imperative of saving lives at sea, either by acting out of humanitarian considerations and/or by following international obligations for rescue at sea. National authorities and courts need to find a right balance between applicable international and EU law, and national law, as complemented by non-legally binding guidance, such as the Italian Code of Conduct and similar domestic instructions. The 2017 UNHCR guidance on search and rescue operations at sea, including the non-penalisation of those taking part in these activities, gives useful guidance in this regard.

The note provides an overview of recent criminal investigations in Greece, Italy and Malta against NGOs owning these search and rescue ships and/or against individual crew members. It draws on past FRA materials on the non-criminalisation of persons engaging with migrants in an irregular situation for humanitarian reasons. A 2014 FRA paper recommended that European Union (EU) Member States should implement the Facilitation Directive (Directive 2002/90/EC) in a fundamental rights compliant manner, and practical guidance should be developed for this purpose. The paper emphasised that such guidance needs to explicitly exclude punishment for humanitarian assistance ‘at entry’ to the EU of migrants in an irregular situation, including when rescuing at sea.

Recent EU policy developments have brought this issue again to the forefront, as activities to implement the EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling (2015-2020) continued and intensified. In March 2017, the European Commission published its evaluation of the Facilitation Directive and Council Framework Decision 2002/946/JHA. It concluded that there is no need to revise the EU facilitation acquis, but clearly acknowledged that some actors, including civil society organisations involved in search and rescue operations at sea, perceive a risk of criminalisation of humanitarian assistance.

- Providing assistance to people in distress at sea (search and rescue – SAR) is a duty of all states and shipmasters under international law. Core provisions on SAR at sea are set out in the 1974 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR Convention), and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In general, the shipmaster (of both private and government vessels) has an obligation to render assistance to those in distress at sea without regard to their nationality, status, or the circumstances in which they are found. The 1979 SAR Convention obliges States to establish maritime rescue coordination centres (MRCC) and outlines operating procedures to follow in the event of emergencies and during SAR operations. Based on state information, the International Maritime Organisation divided the world’s oceans into different SAR zones, each with its own coordination party.

- All EU Member States except Ireland have ratified the UN Smuggling of Migrants Protocol (2000), which supplements the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (2000). It requires states to criminalise the procurement of irregular entry or residence of migrants to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit (Article 6). Aggravating circumstances should be established if there is a threat to the lives or safety of migrants, or in the case of inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 6 (3) (a) and (b)). According to the Interpretive Notes to the UN Smuggling of Migrants Protocol (paragraph 92), the reference to financial or other material benefit for the perpetrator is intended to exclude family members (this line was followed by the European Court of Human Rights in Mallah v. France, paragraphs 33-42), or other support groups such as religious or non-governmental organisations from punishment.

- Under EU law, the Facilitation Directive and its accompanying Framework Decision 2002/946/JHA further specify these obligations. This so-called ‘EU Facilitation Package’ obliges EU Member States to punish anyone who assists a person to irregularly enter, transit or stay in the territory of a Member State. Member States may, however, refrain from punishment if the aim of enabling the migrant in an irregular situation to enter or transit through the country is to provide that person with humanitarian assistance (Article 1 (2) of the Facilitation Directive). The Regulation establishing the European Border and Coast Guard (Regulation (EU) 2016/1624) also recognises that the Facilitation Directive mandates Member States to refrain from imposing sanctions where the aim of the behaviour is to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants (Recital (19)). In July 2018, the European Parliament formulated guidelines for Member States to prevent humanitarian assistance from being criminalised. In addition, failure to respect the duty to rescue is usually a criminal act in several EU Member States, as FRA found in its 2013 report on Fundamental rights at Europe’s southern sea borders (p. 35). However, FRA research has highlighted the risk that EU Member States’ domestic legislation on the facilitation of entry and stay of irregular migrants may lead to the punishment of those who provide humanitarian assistance, as well as private entities carrying out SAR operations at sea.

- Migrant smuggling, including facilitation of irregular entry is punishable in all 28 EU Member States. Following the broad definition under the Facilitation Directive, legislation in the overwhelming majority of Member States does not require financial gain or other material benefit for such an act to be a punishable offence. National legislation often does not reflect the safeguard in Article 1 (2) of the Facilitation Directive, which allows Member States not to impose sanctions when irregular entry of migrants is facilitated for humanitarian purposes. As of now, the domestic law of only nine EU Member States exempts certain acts carried out to facilitate entry for humanitarian purposes from punishment for migrant smuggling, according to the Commission’s 2017 evaluation report on the ‘EU Facilitation Package’.

- The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights has been working extensively on the issues of facilitation of irregular entry, humanitarian assistance and fundamental rights – see the reports on the rights of migrants in an irregular situation (Chapter 5), Europe’s southern sea borders (Chapter 2), criminalisation of migrants in an irregular situation and of persons engaging with them, as well as the 2018 Fundamental Rights Report (Sub-section 6.3.3). In these reports, FRA has repeatedly underlined that actions against migrant smuggling must not result in punishing people who support migrants on the move for humanitarian considerations, including persons working for NGOs saving lives during search and rescue operations. The same principle is recalled by the 2018 UN Principles and Guidelines, supported by practical guidance, on the human rights protection of migrants in vulnerable situations (Principle 4.7), elaborated jointly by the Global Migration Group and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights of the United Nations. In this context, it is to be highlighted that fully respecting the right to life (Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU and the European Convention on Human Rights) and the duty to save lives at sea (enshrined in multiple maritime law treaties, such as the 1974 SOLAS Convention, the 1979 SAR Convention and the 1982 UNCLOS) rest primarily on EU Member States. These obligations of fundamental character cannot be circumvented under any circumstances, including for considerations of external border controls.

- In the Central Mediterranean Sea, vessels deployed by civil society organisations have played an important role in search and rescue at sea. For instance, according to an inquiry by the Italian Senate, during the first six months of 2017 (1 January-30 June), some 10 vessels deployed by NGOs rescued more than a third of the persons rescued at sea in this period (33,190 of the 82,187 persons). In the year 2017 and until June 2018, such NGO vessels carried out roughly 40 % of all rescues, the Italian Coast Guard reported.

Nevertheless, allegations that some NGOs are cooperating with smugglers in Libya prompted a shift in perceptions of their contribution. The Italian Senate, which examined this issue in detail in the spring of 2017, dismissed such allegations. It found that NGOs were not involved directly or indirectly in migrant smuggling, but recommended better coordination of their work with the Italian Coast Guard.

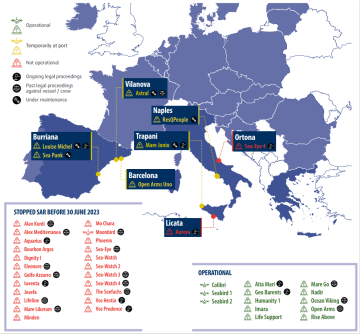

In the downloadable file at the bottom of the page, table 1 gives an overview of all NGOs and their vessels and reconnaissance aircrafts involved in search and rescue operations during the past years in the Mediterranean. It shows that only a few NGO rescue vessels were operational in August 2018 due to various reasons, including ship seizures ordered by the EU Member State authorities of disembarkation. None of them was deployed in Italy’s SAR zone as of the end of August 2018.

- Building on the EU Action Plan of July 2017 to support Italy and reduce pressure along the Central Mediterranean route, a Code of Conduct for NGOs involved in search and rescue activities was drawn up last summer, in consultation with the European Commission and some of the relevant NGOs. The Code of Conduct prohibits NGOs from entering Libyan territorial waters, envisages the presence of police officers aboard NGO vessels, bans NGOs to communicate with smugglers, forbids NGOs to switch off their transponders, and obliges them not to obstruct the Libyan coast guard. Several civil society organisations criticised the code, arguing that it would increase the risk of casualties at sea. Some NGOs signed the code, while others – such as Médecins Sans Frontières or Jugend Rettet – refused, indicating that it mixes EU migration policies with the imperative of saving lives at sea.

- Since the summer of 2017, the Italian authorities have started taking measures, including seizing ships and launching criminal as well as administrative investigations to address actions by NGO-deployed vessels considered to exceed their rescue-at-sea activities. Some actors consider certain practices that some SAR NGOs follow as blurring the lines when it comes to the legality of such actions. During the summer of 2018, Malta also initiated investigations and blocked search and rescue operations by NGOs off their coasts and in the adjacent airspace. Humanitarian helpers taking part in rescue at sea activities became target of investigations and criminal charges in Greece as well. These legal proceedings and administrative measures have to deal with the delicate question of determining the scope of acts covered by the humanitarian exception clause excluding punishment for what would otherwise be deemed smuggling of migrants.

- In the downloadable file at the bottom of the page, table 2 portrays the ongoing or closed investigations and criminal proceedings against the rescue vessels concerned and/or its individual crew members, of which FRA is aware (having reviewed publicly available sources). It shows that most opened cases ended with an acquittal or were discontinued due to the lack of evidence.

- The criminalisation of SAR NGOs has become a significant phenomenon in the EU. As Table 2 demonstrates, it concerns three of the four EU Member States – Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain – which are affected by irregular arrivals by sea in the Mediterranean. In these EU countries, NGO ships rescuing migrants at sea have been seized, and investigations and criminal proceedings have been initiated against crew members of such vessels and other private individuals taking part in rescue operations. The increasing number of legal actions against NGOs has contributed to a drop in dedicated and effective search and rescue assets in the Mediterranean at a time when death at sea remain high (see figure 1). In the downloadable file at the bottom of the page, figure 1 shows, although the total number of arrivals by sea decreased in 2018, the proportion of deaths compared to the total number of arrivals increased in 2018 compared to 2017. When comparing the first eight months of 2018 (January-August) to the same period of 2017, this ratio increased from 1.85 % to 2.13 %, according to data collected by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

- FRA will continue to follow closely further developments, also through its periodic overviews of migration-related fundamental rights concerns covering 14 selected EU Member States, including Italy and Greece.