The key role of civil society is reflected in the EU treaties. Article 11 (2) of the TEU and Article 15 (1) of the TFEU consider civil dialogue and civil society participation as tools for good governance. It is also reflected in relevant EU policy documents, such as the EU Strategy to strengthen the application of the Charter, the European Democracy Action Plan and action plans on anti-racism, LGBTIQ+ equality, Roma inclusion, children’s rights, disability, victims’ rights, women’s rights and migrant integration.

Civil society’s expertise, services, advocacy and watchdog role are key to the implementation of fundamental rights in the EU. Therefore, FRA reports on civic space developments across the EU have been published annually since 2018.[1] See FRA’s web page on civic space.

Various challenges and pressures hamper the important work of CSOs and human rights defenders across the EU in the areas of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. These are referred to as ‘civic space challenges’.

Reports by international organisations and a range of CSOs have pointed to persisting serious challenges for civil society in the EU. FRA’s annual reports on civic space have also highlighted the serious challenges civil society faces.[2] FRA (2021), Protecting civic space in the EU, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union (Publications Office); FRA (2022),Europe’s civil society: Still under pressure – Update 2022, Luxembourg, Publications Office. FRA’s research and the findings from its annual consultations with civil society point to patterns of challenges for CSOs regarding:

- the legal frameworks governing their work and their participation in democracy and the rule of law;

- access to resources;

- participation in policymaking and decision making;

- operating in a safe environment.

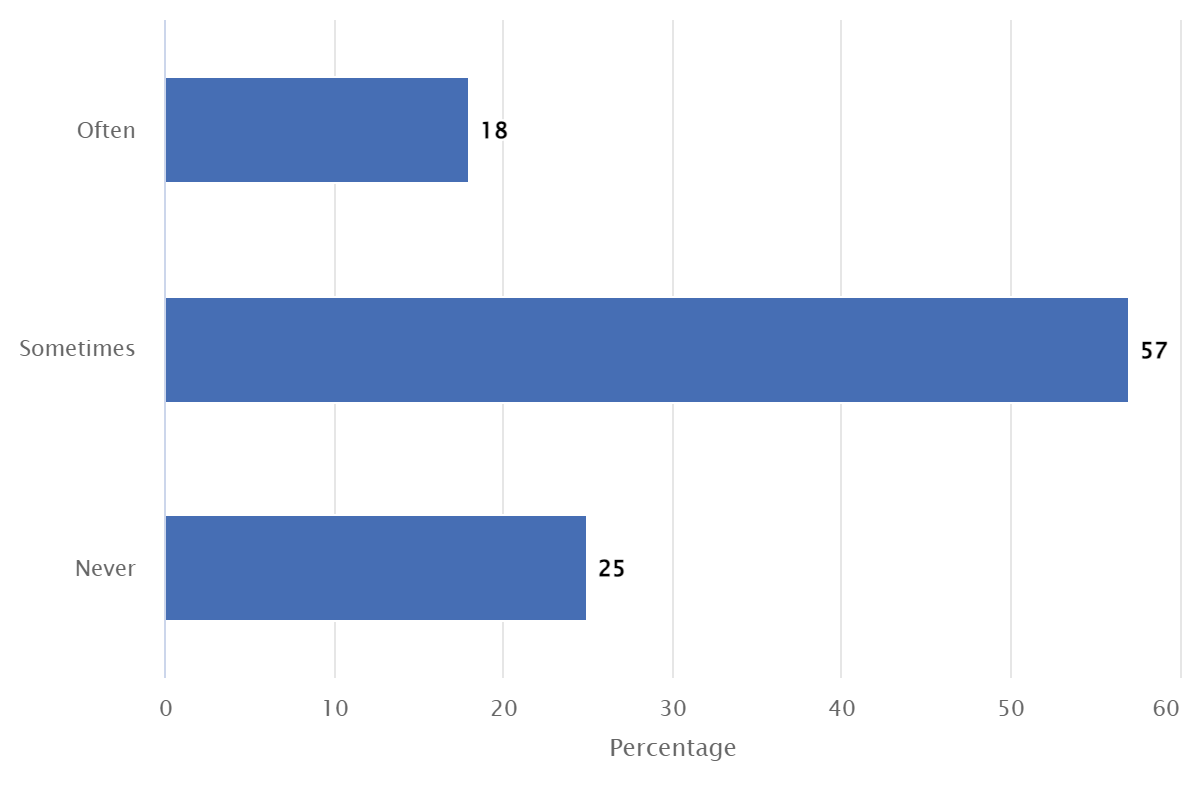

The graphs in this report summarise the responses from representatives of close to 400 CSOs working in the area of human rights at EU, national and local levels in the EU. Their responses cover their experiences in civic space in 2022.

A range of CSOs point to persisting serious challenges for civil society in the EU, limiting their role and contribution to the functioning of democracy and the rule of law (see Figure 1). Compared to the situation in 2018, the conditions for working on human rights has gotten worse (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 – How often CSOs faced barriers in conducting their human rights activities in 2022 (%)

A bar chart showing that 18% of organisations often faced barriers in 2022. 57% of organisations sometimes faced barriers and 25% never faced barriers.

Notes: Question: “In the last 12 months, did you face any barriers in conducting your activities for human rights and the rule of law?” N = 359.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

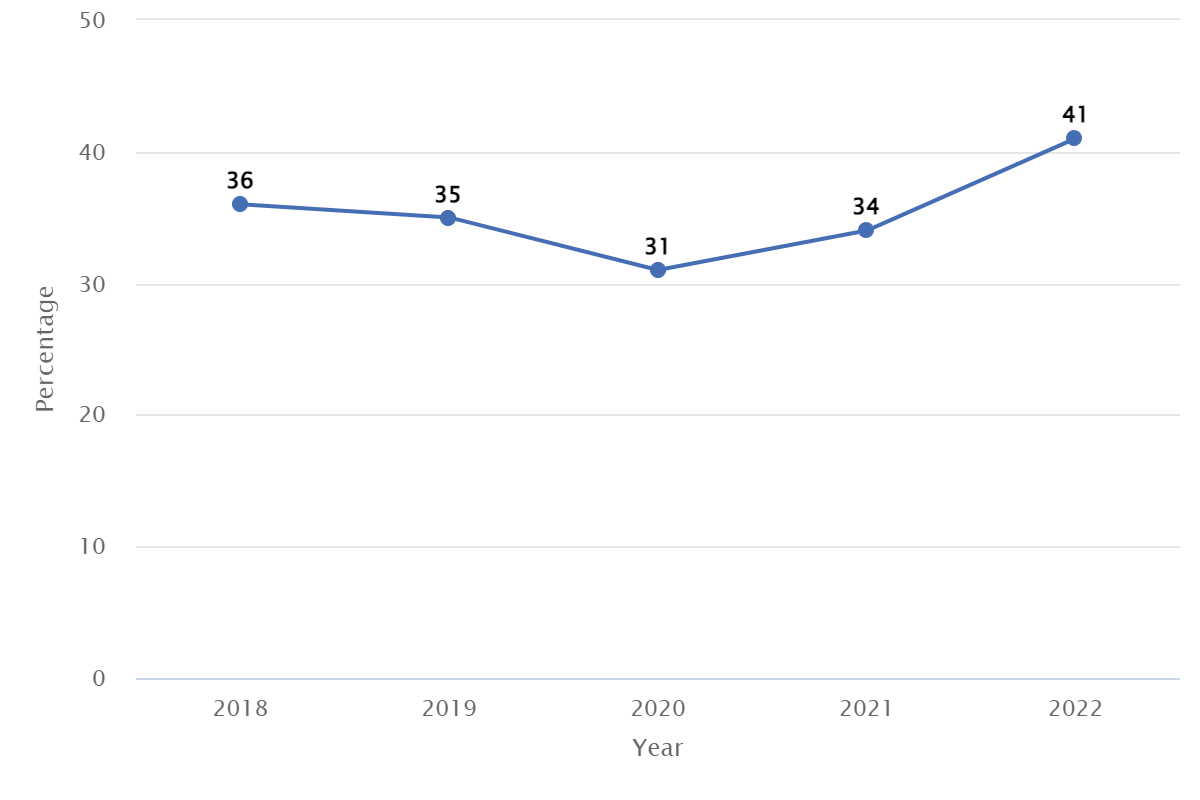

Figure 2 – General conditions for CSOs working on human rights – respondents indicating ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ (%)

Notes: Question: “How would you describe in general the conditions for CSOs working on human rights issues in your country today? (very good/good/neither good nor bad/bad/very bad)” The figure shows the percentage of those responding ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. 2018, N = 136; 2019, N = 145; 2020, N = 297; 2021, N = 286; 2022, N = 318.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018–2022

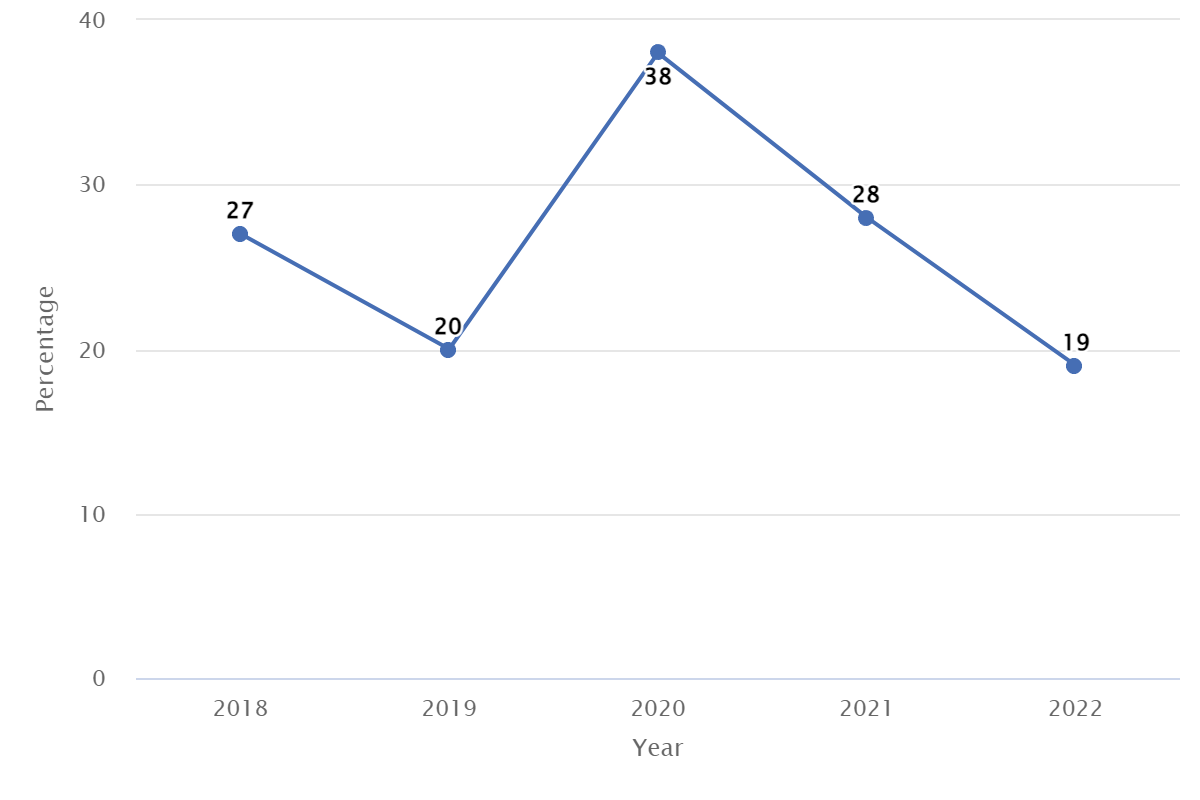

Figure 3 – CSOs perceiving a change in their own situation in 2022 – respondents indicating ‘deteriorated’ or ‘greatly deteriorated’ (%)

A line chart showing that between 2018 and 2022 organisations who perceived that their own situation had ‘deteriorated’ or ‘greatly deteriorated’ reached a peak of approximately 37% in 2020 and then dropped down to 20% in 2022 which was the same level as 2019.

Notes: Question: “Thinking about your own organisation, how has its situation changed in the past 12 months? (greatly improved/improved/remained the same/deteriorated/greatly deteriorated)” 2018, N = 133; 2019, N = 202; 2020, N = 393; 2021, N = 387; 2022, N = 407. For 2018, the question referred to the past three years.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018-2022

A higher number of organisations perceived their situation as having improved from the previous year in 2022 than in previous consultations, and a lower number witnessed a deterioration (18 % compared with 28 % in 2021) (Figure 3). To a large extent this can be related to the ending of COVID measures, notably emergency measures which greatly affected CSOs. [3] FRA (2021), COVID-impact on civil society work: Results of consultation with FRA’s Fundamental Rights Platform, 24 February 2021.

In terms of policy measures by authorities, FRA’s research reveals both positive and negative developments in 2022 across the EU. Positive steps in several Member States include policy measures creating an environment more conducive to the development of civil society , the strengthening of cooperation between public authorities and CSOs including through setting up cooperation bodies, and the improvement of frameworks for participation. For example, some Member States have created infrastructures aimed at providing space for dialogue, channelled targeted support to civil society, or undertaken specific commitments to create an enabling environment in national action plans for an open government. CSOs have also been active in their efforts to improve the policy framework in which they operate, including through coalition building.[4] Franet’s country studies on civic space for the 27 Member States.

In 2022–2023, all three major EU institutions e acknowledged civic space pressures in the EU in official documents for the first time:

2022 was an important year for civic space-related legislative and policy developments. The European Commission dedicated its annual report on the application of the Charter to the topic ‘A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU’. It reviewed the situation of civil society organisations and other human rights defenders, concluding that they need more support and that their operating environment needs improvements.[5] European Commission (2022), A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU: 2022 annual report on the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, COM(2022) 716 final, Brussels, 6 December 2022.

The Commission announced in the report that it would launch targeted dialogue with stakeholders through a series of thematic seminars on safeguarding civic space. The seminars focused on how the EU can further develop its role to protect, support and empower CSOs and rights defenders to address the challenges and opportunities identified in the report. The outcome of the seminars will be discussed at a high-level conference in November 2023. [6] European Commission (2023), ‘A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU: looking forward - Follow up seminars to the 2022 Report on the Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights’, (forthcoming).

Proposals for EU legislation of direct relevance to CSOs were also put forward in 2022.

In February 2022, the European Parliament called for “a dedicated, comprehensive strategy to strengthen civil society in the Union, including by introducing measures to facilitate the operations of non-profit organisations at all levels”.[7] European Parliament (2022), Resolution with recommendations to the Commission on a statute for European cross-border associations and non-profit organisations, P9_TA(2022) 0044, Strasbourg, 17 February 2022, para. 33.

In particular, the Parliament called for a legislative initiative to create a statute for European cross-border associations and non-profit organisations.[8] European Parliament (2022), Resolution with recommendations to the Commission on a statute for European cross-border associations and non-profit organisations, P9_TA(2022) 0044, Strasbourg, 17 February 2022.

The resolution calls on the Commission to recognise and promote the public benefit activities of non-profit organisations by harmonising the conditions for granting public benefit status within the EU. In response to the European Parliament’s call on 5 September 2023, the Commission adopted, a proposal for a directive on European cross-border associations. [9] European Commission (2023), Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on European cross-border associations, COM(2023) 516, 5 September 2023.

The proposal supplements the existing national legal forms of associations with a new legal form, European cross-border associations (ECBA). It seeks to make it easier for non-profits to be active in more than one Member State. After registration in one Member State, the proposal allows automatic recognition of ECBAs across the EU. It also provides for harmonised rules on the transfer of registered office [10] European Commission (2023), Commission facilitates the activities of cross-border associations in the EU, Press release, 5 September 2023.

.

In addition, in April 2022 the European Commission proposed a directive on SLAPPs. These will most probably be adopted at the end of 2023 (for details, see Section 2.2).

Surveillance was also a prominent topic in 2022. Following alleged abuses in the use of Pegasus and similar surveillance software against a variety of targets, including CSOs, the European Parliament set up a committee of inquiry to investigate them.[11] European Parliament (2022), Decision on setting up a committee of inquiry to investigate the use of the Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware, and defining the subject of the inquiry, as well as the responsibilities, numerical strength and term of office of the committee, P9_TA(2022) 0071, Strasbourg, 10 March 2022.

The committee published a report on its findings in May 2023.[12] European Parliament (2023), Report of the investigation of alleged contraventions and maladministration in the application of Union law in relation to the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware, 22 May 2023; European Parliament (2023), European Parliament draft recommendation to the Council and the Commission following the investigation of alleged contraventions and maladministration in the application of Union law in relation to the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware, P9_TA(2023) 0244, 22 May 2023. See also FRA (2023), ‘Surveillance by intelligence services: Fundamental rights safeguards and remedies in the EU – 2023 update’, 24 May 2023.

Moreover, in September 2022, the European Commission proposed a European media freedom act, consisting of a proposed regulation and a recommendation for editorial independence and ownership transparency in the media sector.[13] European Commission (2022), Proposal for a regulation establishing a common framework for media services in the internal market (European Media Freedom Act) and amending Directive 2010/13/EU, COM(2022) 457 final, Brussels, 16 September 2022.

The proposed legislation included safeguards against political interference in editorial decisions and against surveillance. It focuses on the independence and stable funding of public service media, and on the transparency of media ownership and of the allocation of state advertising. The draft envisages the formation of a European board of media services. The board will, organise a “structured dialogue between providers of very large online platforms, representatives of media service providers and representatives of civil society” to foster access to diverse independent media on very large online platforms and discuss experiences and best practices.[14] European Commission (2022), Proposal for a regulation establishing a common framework for media services in the internal market (European Media Freedom Act) and amending Directive 2010/13/EU, COM(2022) 457 final, Brussels, 16 September 2022, Art. 12 (l).

CSOs benefit from and require diverse and free media to make their voice heard.

The Digital Services Act, which entered into force in 2022, establishes various mechanisms allowing for CSO engagement. [15] Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a single market for digital services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC, OJ 2022 L 277 (Digital Services Act).

Options include launching complaints and engaging in the identification of societal risks and their evolution in the context of drawing up codes of conduct and crisis protocols.[16] Digital Services Act, Articles 45, 46 (1), 47 (1) and 49 (3).

Finally, 2022 also saw the preparations of the European Commission’s Defence of Democracy Package. The plan was announced in the President of the Commission’s State of the Union speech. While the initiative is aimed at promoting transparency and fighting foreign interference, concerns were raised by some stakeholders about possible negative implications for fundamental rights and ultimately the work of CSOs.[17] See, for instance, the joint civil society declaration EU foreign interference law: Is civil society at risk? Why we are against an EU FARA law.

The Commission announced in June 2023 that it would further consult and gather additional information as part of a full impact assessment. According to the European Commission, this will involve carefully looking at enhanced transparency, democratic accountability, freedom of expression and freedom of association.

In its December 2022 report on civic space in the EU, the European Commission underlined that CSOs and rights defenders continue to report a range of challenges and restrictions that limit their ability to carry out their activities.[18] European Commission (2022), A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU – 2022 annual report on the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, COM(2022) 716 final, Brussels, 6 December 2022, p. 13.

The European Commission found during its consultation for the report that 61 % of responding CSOs had faced obstacles that limit their ‘safe space’.[19] European Commission (2022), 2022 report by the European Commission on the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights: A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU – Consultation of civil society organisations, p. 9.

As a follow-up to its report, the Commission convened three expert seminars. One of them focused on protection.[20] European Commission (2023), Summary Report, A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU: looking forward - Follow up seminars to the 2022 Report on the Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (forthcoming)

Leading civil society umbrella organisations organised a major gathering in December 2022. It brought together over 100 representatives of civil society, EU and international institutions, and donors to discuss how to enable, protect and expand Europe’s civic space. Those gathered developed recommendations for the European Commission.[21] European Civic Forum (n.d.), ‘European Convening on Civic Space’.

At the gathering, the organisations called for “an EU mechanism to protect civil society and human rights defenders that should be built on the example of the existing external EU human rights defenders’ mechanism protectdefenders.eu, the mechanism developed by DG IntPA [the Directorate-General for International Partnerships] to support civil society in the External Action, as well as the Council of Europe Platform for safety of journalist[s] and the UN Special Procedures”.[22] European Civic Forum and Civil Society Europe (2023), ‘How can we enable, protect and expand Europe’s civic space, to strengthen democracy, social and environmental justice? Recommendations for the European Commission’.

The CERV programme, introduced in 2021, continued to provide funding for civil society actors in the EU in 2022.[23] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme’.

The programme also gives umbrella CSOs the opportunity to receive core funding and to regrant it to their member organisations. While CSOs praise these developments overall, they continue to criticise the administrative burden and lack of flexibility associated with this programme.[24] European Commission (2023), Summary Report, A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU: looking forward - Follow up seminars to the 2022 Report on the Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (forthcoming)

Article 11 of the TEU defines civil dialogue as an essential component of participatory democracy and requires EU institutions to “give citizens and representative associations the opportunity to make known and publicly exchange their views in all areas of Union action” and to “maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”. The European Commission considers the participation of civil society as key to ensuring good-quality legislation and the development of sustainable policies that reflect people’s needs.[25] European Commission (2013), Guidelines for EU support to civil society in enlargement countries, 2014–2020, 22 October 2018.

Several EU strategies and action plans in the field of fundamental rights envisage the setting up of various forms of civil society forums/platforms, working groups, etc., to facilitate dialogue and structured cooperation between authorities and civil society and the implementation of the strategies and plans. Such strategies and action plans often call for the adoption of national action plans, which can also benefit from civil society participation.

For instance, under the EU Roma Strategic Framework for Equality, Inclusion and Participation for 2020–2030, the European Commission set out to facilitate the participation of Roma non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as full members of national monitoring committees for all programmes addressing needs of Roma communities. It has thereby capacitated and engaged at least 90 NGOs in EU-coordinated Roma civil society monitoring, encouraging the participation of Roma in political life at local, regional and EU levels.[26] European Commission (2020), EU Roma strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation for 2020–2030, COM(2020) 620 final, Brussels, 7 October 2020.

Similarly, the Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027 concerning migrant integration refers to the European Commission’s launch of an expert group on the view of migrants. The group is composed of migrants and organisations representing their interests, to be consulted on the design and implementation of future EU policies in the field of migration, asylum and integration.

Building on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and related treaties, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders of 1998 explicitly lists the rights and responsibilities of human rights defenders.[27] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (1998), Declaration on the right and responsibility of individuals, groups and organs of society to promote and protect universally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms, A/RES/53/144, 9 December 1998.

In line with the overall UN General Assembly mandate to promote and protect human rights,[28] OHCHR (n.d.), ‘High Commissioner’.

the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights seeks to expand civic space and to strengthen the protection of human rights defenders around the globe. His office monitors and advocates around numerous cases of defenders under threat.

It also acts as the custodian of Sustainable Development Goal indicator 16.10.1 on verified cases of killing, kidnapping, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention and torture of journalists and associated media personnel, trade unionists and human rights advocates.

UN human rights treaty bodies have raised issues concerning civic space and the need for an enabling environment for the activities of CSOs and human rights defenders. The work of most, if not all, UN Human Rights Council appointed Special Procedures mandate holders touches on issues related to human rights defenders and civic space.[29]

See for example, OHCHR (2018), General Comment No. 36 on Article 6: Right to Life, 30 October 2018, paras. 23 and 53; OHCHR (2020), General Comment No. 37 on Article 21: Right of peaceful assembly, 23 July 2020, para. 30; OHCHR (2022), General recommendation No. 39 on the rights of Indigenous Women and Girls, 31 October 2022, especially paras. 45-46.

Online and offline civic space was among the thematic spotlights of the UDHR75 campaign that began in 2023. [30]

OHCHR (2023), Human Rights 75 Initiative: Monthly thematic spotlights.

The mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders to promote the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders’ effective implementation was established in 2000.[31] OHCHR (n.d.), ‘Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders’.

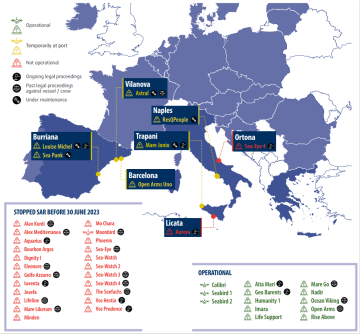

In 2022, the Special Rapporteur published a report on defenders of the rights of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers,[32] OHCHR (2022), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders – Refusing to turn away: Human rights defenders working on the rights of refugees, migrants and asylum-seekers, 18 July 2022.

and made numerous statements in recognition of issues specific to human rights defenders.[33] OHCHR (n.d.), ‘Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders’.

The work of most, if not all, of the UN Human Rights Council-appointed special procedures mandate holders[34] OHCHR (n.d.), ‘Special procedures of the Human Rights Council’.

touches on issues related to human rights defenders and civic space.

Moreover, following the establishment of the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention in October 2021, the Meeting of the Parties to the Aarhus Convention elected Michel Forst as the first special rapporteur in this area in June 2022.[35] United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) (n.d.), ‘Special Rapporteur on environmental defenders under the Aarhus Convention’.

The special rapporteur’s primary role is to provide a rapid response to protect environmental defenders from persecution, penalisation and harassment.

Similarly, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights continued to support human rights defenders and civil society and to promote an enabling environment in accordance with her mandate. This included meeting them regularly, intervening in cases where they had faced risks to their personal safety, liberty and integrity, participating in the proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights, and co-operating with other international mandates and stakeholders throughout 2022.[36] Council of Europe (n.d.) Commissioner for Human Rights: Human rights defenders.

The Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly also continued to work on civic space issues. It adopted a report and a recommendation on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on civic space.[37] Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly (2022), The impact of the Covid-19 restrictions on civil society space and activities.

The assembly also produced a report and a resolution on transnational repression, which was subsequently adopted in 2023.[38] Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly (2023), Transnational repression as a growing threat to the rule of law and human rights, 23 June 2023.

In 2022, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) published a resilience tool for national human rights institutions. Its findings are also relevant for human rights defenders more broadly.[39] Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (2022), Strengthening the resilience of NHRIs and responding to threats – Guidance tool, Warsaw, OSCE/ODIHR.

ODIHR also offered a range of training programmes for civil society on human rights monitoring and related security issues.

In December 2022, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a landmark report entitled The protection and promotion of civic space: Strengthening alignment with international standards and guidance, which covers the EU.[40] OECD (2022), The protection and promotion of civic space: Strengthening alignment with international standards and guidance, Paris, OECD Publishing, Section 5.6.

The OECD will also publish a practical guide for policymakers on the protection and promotion of civic space in 2024. In addition, the OECD is conducting country assessments on civic space, which are qualitative reviews of the laws, policies, institutions and practices that support civic space in OECD member and partner countries.[41] OECD (2022), ‘Civic space scan’.

In 2022–2023, two EU countries were covered: Portugal[42] OECD (forthcoming), Civic space review of Portugal: Towards people-centred, rights-based public services.

and Romania.[43] OECD (2023), Civic space review of Romania, Paris, OECD Publishing; OECD (2023),Empowering citizens, strengthening democracy: Insights on open government and civic space in Romania.

FRA has granted three EU candidate countries – Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia – observer status. Hence, it covers these three countries in its work. Franet research on civic space also covers these, and FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation collected responses from 30 CSOs across these countries. Developments in civic space in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia show similar patterns to those in the EU.

The main difficulties that CSOs encountered in 2022 in these three countries concerned access to information, legislation on civil dialogue and consultations, transparency and lobbying laws, and anti-money laundering measures.[44] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation (in Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia).

Fewer CSOs said their organisation’s conditions had worsened compared with the previous year in 2022. Still, around 20 % of respondents saw their situation as having deteriorated, whereas roughly 6 % believed it had greatly deteriorated.[45] Ibid.

In comparison, 16 % in EU Member States said their situation had deteriorated, and around 2 % said it had greatly deteriorated.[46] Ibid.

One quarter of responding CSOs experienced difficulties in terms of enjoying their right to freedom of peaceful assembly.[47] Ibid.

In Albania and Serbia, CSOs referred to obstacles to exercising this right. In these countries, human rights organisations carried out activities aimed at monitoring the compliance of police procedures with national and international standards on peaceful assembly. In Serbia, in September 2022, public authorities attempted to ban the peaceful LGBTIQ+ EuroPride march and restrict protests for environmental rights.

North Macedonian and Serbian CSOs complained of a lack of an enabling environment. Problems arose particularly in their cooperation with public authorities. CSOs reported that SLAPPs are used to silence civil society.

In Serbia, environmental defenders and activists denouncing bad health practices during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic faced lawsuits. In North Macedonia, a working group composed of state institutions’ representatives and CSOs drafted a legislative proposal aimed at providing a process for legal gender recognition. It was withdrawn after reaching the parliament, following fake news and transphobic propaganda.[48] Ibid.

These events are reflected in the overall trend evident from FRA’s civic space consultation, where almost half of respondents reported that their organisation was a victim of negative media reports and/or campaigns in 2022. Moreover, almost half of respondents experienced online and/or offline threats or harassment due to their work.[49] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation (in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia).

A recurring negative pattern in all three countries, particularly Albania and Serbia, concerns environmental defenders, who reportedly often face lawsuits and harassment. However, promising practices indicate that CSOs are willing to proactively and collectively protect civic space and to promote citizens’ participation in decision-making processes. This was, in some cases, achieved through civil society-led umbrella initiatives. For instance, in North Macedonia the Skopje-based European Policy Institute and the Deliberative Democracy Lab at Stanford University organised a third deliberative poll on the topic of elections and electoral reforms, which involved about 150 citizens. A deliberative poll takes a random, representative sample of citizens and engages them in deliberation on current issues or proposed policy changes through small group discussions and conversations with experts to obtain a more informed and reflective public opinion.

In other cases, cooperation between CSOs and public authorities led to significant results. In Albania, the non-profit sector, the state and financial authorities jointly developed a methodology aimed at assessing the risk of terrorist financing in the non-profit sector. Finally, a training initiative in North Macedonia aimed to raise awareness of corruption, build capacity to tackle it and enhance transparency. It brought together the CSO Center for Civil Communication and employees in local government and local public enterprises.[50] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation (in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia).

Another relevant development concerns the Albanian NHRI that gained additional competences to serve as a focal point for monitoring challenges facing human rights defenders in 2022. [51]ENNHRI (2022), State of the Rule of Law in Europe in 2022: Reports from National Human Rights Institutions: Albania.