5.1. Provisions on the legal obligation of professionals to report cases of abuse

According to Article 19(2) of the CRC (emphasis added):

‘[s]uch protective measures should, as appropriate, include effective procedures for the establishment of social programmes to provide necessary support for the child and for those who have the care of the child, as well as for other forms of prevention and for identification, reporting, referral, investigation, treatment and follow-up of instances of child maltreatment described heretofore, and, as appropriate, for judicial involvement’.

In integrated child protection systems, the emphasis should be on prevention and the development of generic services such as warning features for children and families. However, identification, reporting and referral procedures regarding children in need of protection are also needed.

Procedures and methods for competent authorities to assess the reporting of cases should reflect the principle of the best interests of the child. They should seek to take children’s views into consideration.

The Barnahus model is a child-friendly and multidisciplinary approach for handling cases of child abuse and exploitation. It provides a safe and coordinated environment for child victims following European standards on child-friendly justice [5] Council of Europe, Committee of Minsters (2010), Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice, Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing. . The model combines medical, legal and support services under one roof to minimise trauma and improve outcomes for the child.

EU Member States should improve identification, reporting and referral mechanisms for children in need of protection. Existing mechanisms should be confidential, well-publicised and accessible to professionals and the general population. They should also be accessible to children and to children’s representatives. The data provide information on professionals’ obligations to report cases falling under the scope of child protection systems.

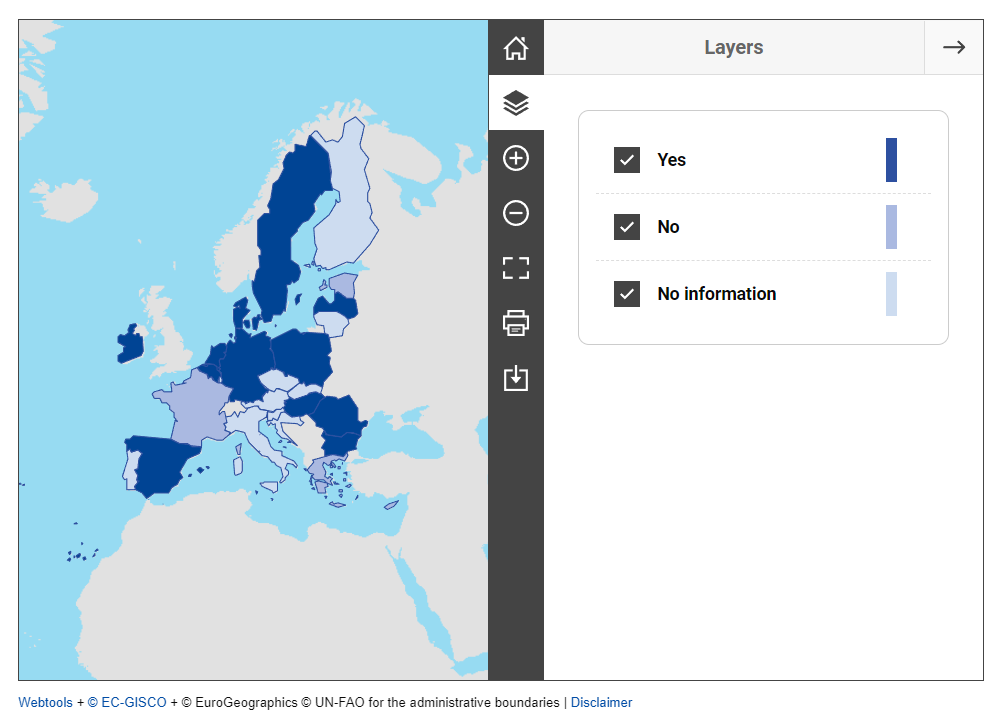

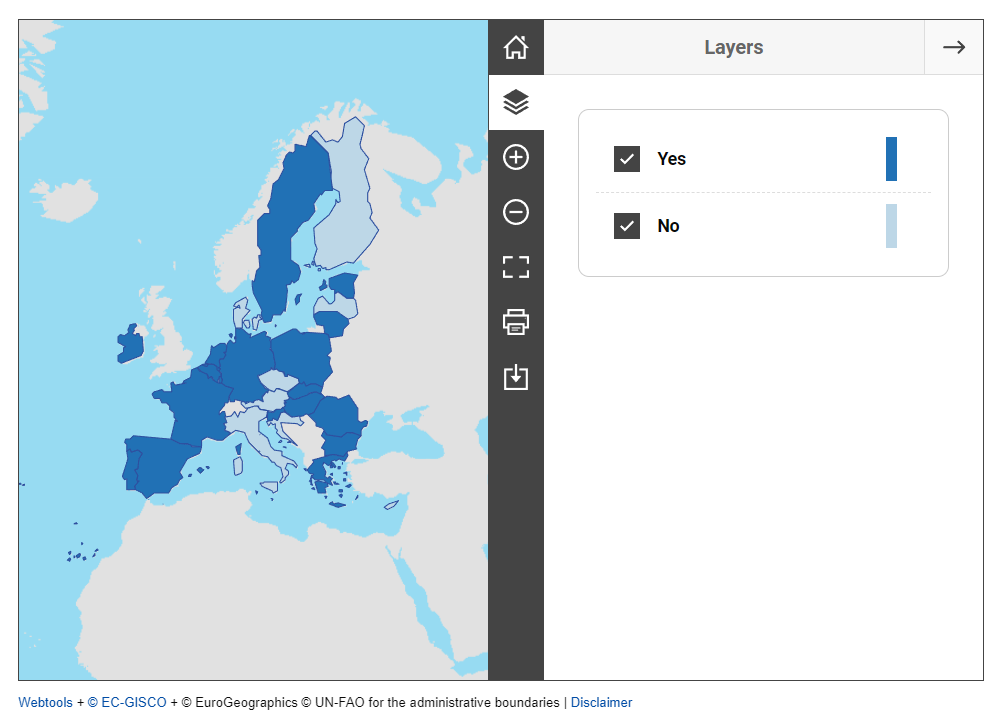

Figure 10 – Provisions on professionals’ legal obligation to report cases of child abuse, neglect and violence

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions on professionals’ legal obligation to report cases of child abuse, neglect and violence. 15 Member States have reporting obligations in place for all professionals. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Most Member States have reporting obligations for some, but not necessarily all, professionals who are in contact with children.

- Some Member States have a comprehensive referral mechanism. However, many lack clear reporting procedures and protocols. This could create delays or lead to under-reporting of cases.

- Lacking a specific, comprehensive procedure for the referral mechanism assigning responsibilities to each actor involved can negatively affect cooperation among professionals.

- An important challenge in tackling under-reporting is professionals’ failure to effectively recognise forms of abuse.

Fifteen Member States have reporting obligations in place for all professionals: Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, France, Croatia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Austria, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden.

In nine Member States (Belgium, Czechia, Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Portugal, Slovakia and Finland), the existing obligations only address certain professional groups, such as social workers or teachers.

Germany, Hungary and the Netherlands had no reporting obligations in place in early 2023.

The anonymity of professionals who report incidents is not always guaranteed in many Member States. This is the case in Denmark, Greece and Lithuania, for example. This lack of anonymity may discourage professionals from reporting a suspected case.

The Barnahus model has become a recommended practice in recent years. Several EU Member States have now established the model: Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Malta, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden. Greece, Spain, France, Cyprus, Latvia, Hungary and Romania are developing their Barnahus projects.

In integrated child protection systems, the emphasis should be on primary prevention and the development of generic services for children and families. Many Member States do not have any obligations for professionals to report cases of abuse. This is because, in some Member States, it does not make any difference whether it is a professional or a member of the public who makes a report.

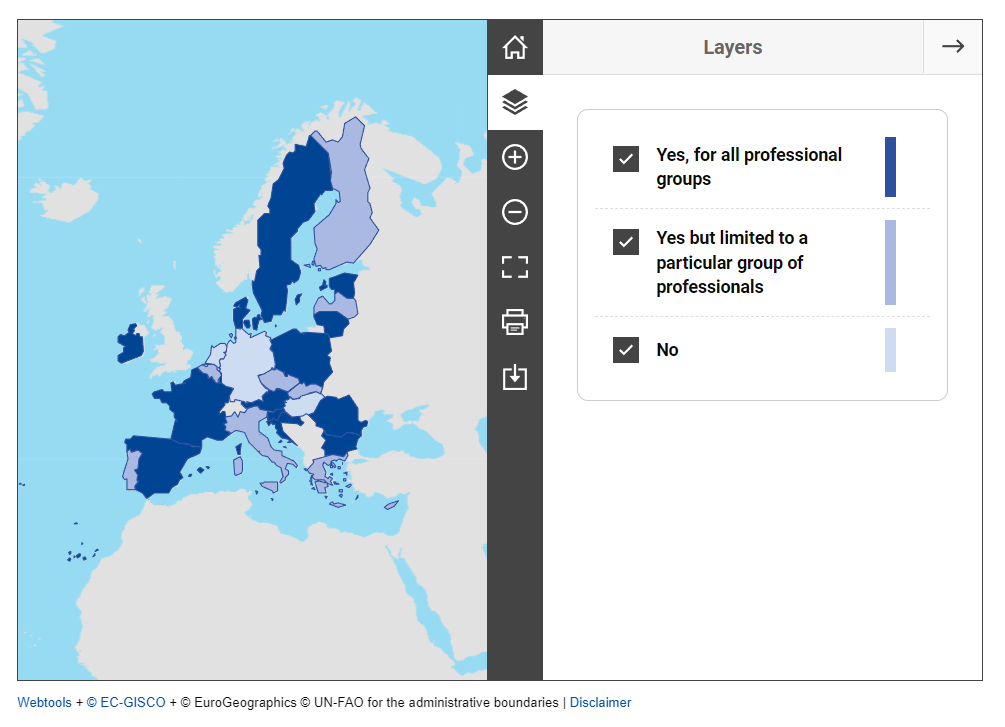

Figure 11 – Specific legal obligations for civilians to report cases of child abuse, neglect and violence

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions on professionals’ legal obligation to report cases of child abuse, neglect and violence. Most Member States have such provisions. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Most EU Member States have provisions setting forth specific obligations for the public to report cases of child abuse, neglect and/or exploitation, that are within the scope of national child protection systems.

- Some Member States do not have specific provisions, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. The public can report cases of abuse in these countries, but it is not a legal obligation.

- In many Member States without specific provisions, general provisions on the obligation for all citizens to report criminal acts under national law apply. However, there is no particular obligation to report a child at risk or presumed cases of abuse.

Article 12 of the CRC guarantees the right to lodge complaints. This is based on the interpretations of general comment No. 5 (2003) on general measures of implementation of the CRC (paragraph 24) and by general comment No. 12 (2009) on the right of the child to be heard (paragraph 46).

Children placed in alternative care are more vulnerable to abuse and neglect. All services and institutions or facilities responsible for the care and protection of children should inform children of their rights, including the right to file complaints against alternative care staff. Member States should therefore have accessible, confidential and child-friendly complaint procedures in place, even in alternative care systems (see Section 5.4).

Some Member States that have ratified Optional Protocol No 3 to the CRC have committed to more precisely formulated safeguarding of children’s right to lodge a complaint with their national institution.

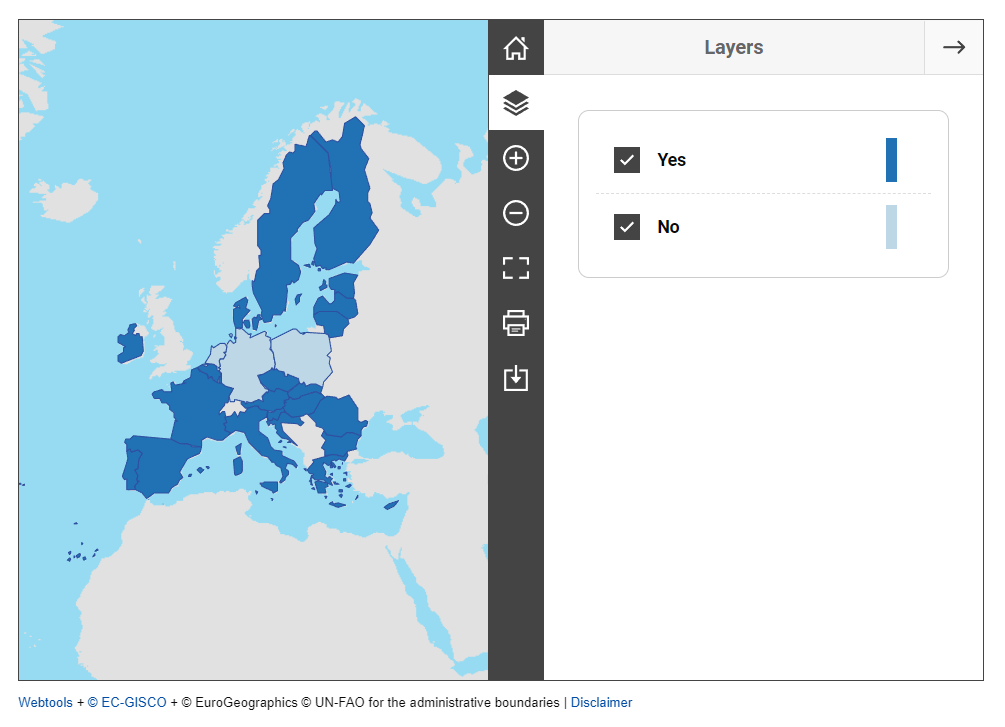

Figure 12 – Provisions on the right of the child placed in alternative care to lodge complaints

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions on the right of the child placed in alternative care to lodge complaints. 25 Member States have such provisions in place. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- All Member States have mechanisms in place aimed at guaranteeing the child’s right to be heard (normally without peremptory age limits) and the right to make maltreatment complaints. The latter right is normally regulated from both a procedural perspective and an age perspective. Typically, officers will try to obtain more information even though they cannot accept complaints from children under 14. If necessary, the officers will report to the prosecutor the need to appoint a special representative to file a complaint on the child’s behalf.

- Even when specific provisions exist, children are not always adequately and systematically informed of their rights. There is often no particular authority or person responsible for informing children of their rights (in a specific, child-friendly way), including their right to report and how to do it.

Almost all EU Member States have provisions addressing the situation and the vulnerability of children in alternative care and their right to lodge complaints, including against alternative care personnel. The exceptions are Italy and Austria.

Italy’s Supervisory Authority for Children and Adolescents receives complaints about violations of the rights protected under the CRC for every child living in the territory. Regional offices receive the complaints. The Italian judicial system has a branch dedicated to handling civil and criminal proceedings involving children.

Children under 14 cannot report crimes or incidents of abuse to law enforcement and judicial authorities. However, they can request representation from an impartial third person. They can ask an adult to report their condition or to call the police.

In Portugal, the Department for Children, the Elderly, and Persons with Disabilities of the Ombuds Institution is responsible for an SOS hotline called Linha Criança. The hotline provides services to children and young people at risk. It can forward cases to the correct institutions. These include the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the National Commission for the Promotion of the Rights and Protection of Children and Youth and the Social Security Institute.

Law No 141/2015 guarantees children’s right for hearings to be private, safe, and peaceful. This means having minimal distracting stimuli and empathetic decorations. These requirements are in compliance with children’s right to access justice and a child-friendly environment.

According to Article 19(2) of the CRC (emphasis added):

‘[s]uch protective measures should, as appropriate, include effective procedures for the establishment of social programmes to provide necessary support for the child and for those who have the care of the child, as well as for other forms of prevention and for identification, reporting, referral, investigation, treatment and follow-up of instances of child maltreatment described heretofore, and, as appropriate, for judicial involvement’.

All services and institutions or facilities responsible for the care and protection of children should establish complaint mechanisms. This is in addition to informing children of their rights, including their right to lodge complaints against alternative care personnel. Alternative care providers should have accessible, confidential and child-friendly reporting procedures in place.

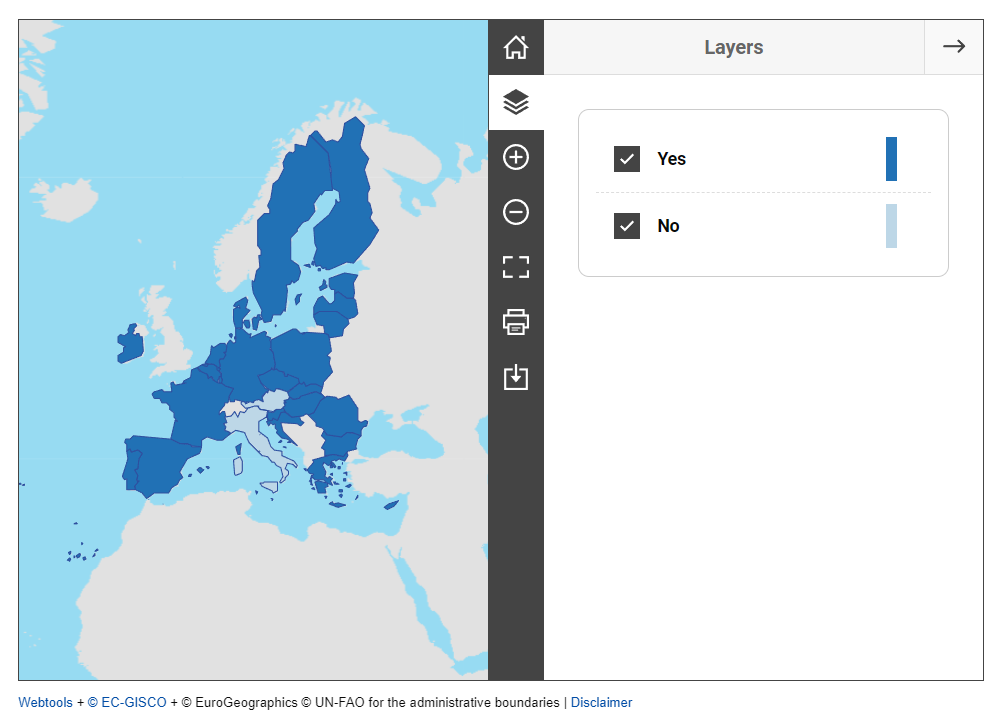

Figure 13 – Specific legal provisions requiring the establishment of complaint mechanisms within alternative care institutions

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions specific legal provisions in place requiring the establishment of complaint mechanisms within alternative care institutions. 19 Member States have such specific provisions. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Nineteen EU Member States have specific provisions on the rights of children in alternative care to lodge complaints. This applies in Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden.

- Eighteen Member States have recently made efforts to establish individual complaint mechanisms within alternative care institutions.

- Reporting mechanisms involve either the national human rights institution (NHRI) (or ombudsperson) or the social welfare system. Government and NGO hotlines or websites provide support.

There are no particular provisions in place in, for example, Italy and Austria. The countries have general provisions establishing the rights of children to report violations of their rights. The provisions also apply to children in alternative care institutions.

In France, children can report abuse or mistreatment in alternative care to the Juvenile Court judge. They can also seek help from a qualified person or complain to the deputy rights defender responsible for children.

Estonia’s Chancellor of Justice Act allows children to contact their caregiver, local government unit child protection assistant and Ombudsman for Children. Institutions must ensure the child’s right to file complaints, provide the opportunity to file complaints independently, record opinions and provide feedback. Institutions must not disclose the child’s identity except in criminal proceedings. Children can also directly contact parents, guardians, child protection officers or the Chancellor of Justice.

Child protection case investigations and family assessments are complex. Therefore, the reference and assessment process of reported cases should involve a participatory, multi-disciplinary assessment of the short-, medium- and long-term needs of the child. This would enhance investigations and responses for children and families.

The views of the child and those of the caregiver and family must be taken into consideration, as Article 12 of the CRC emphasises.

Figure 14 – Provisions requiring a multidisciplinary assessment of child protection cases

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have legal provisions requiring a multidisciplinary assessment of child protection cases. 22 Member States have such provisions. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- All EU Member States have provisions on individual needs assessment requiring the development of a care plan for children. These provisions, however, are not always anchored in law.

- The CRC rights and the principle of the best interests of the child must be enshrined in the national law of all 27 EU Member States. However, most Member States lack criteria and practical guidance on how to assess these.

- Most Member States have provisions on multidisciplinary assessment. These provisions, however, are not regulated by law in some instances. The case manager or the leading social worker on the case must decide whether or not to perform this type of assessment.

- Effective implementation depends on whether provisions of concrete actions and structures exist, and whether they are described in the procedures and protocols.

- Multidisciplinary assessment requirements often apply to second-line assessment.

- In several Member States, existing standards cannot always be applied effectively. This is due to a lack of human resources, the heavy workload of professionals and financial constraints.

In five EU Member States (Greece, Spain, Malta, Slovakia and Sweden) no legal provisions for multidisciplinary assessment of child protection cases were identified. In Germany and Finland, multidisciplinary assessment is possible. However, it is not always applied in practice.

Some Member States, such as the Netherlands, have no mandatory provisions. However, a multidisciplinary team of professionals carries out the assessment de facto. The advice and report centres for child abuse (Advies- en Meldpunten Kindermishandeling) such as Safe at Home, and the Child Care and Protection Board (Raad voor Kinderbescherming) are responsible for assessing cases of potential abuse and deciding on child protection measures. Both have multidisciplinary teams.

Other Member States have developed multidisciplinary teams in the form of panels or other advisory bodies within the system and assigned assessment responsibilities. Member States have subsequently put cooperation protocols in place. In Belgium, for example, the Youth Care Services (Services de l'administration de l'aide à la jeunesse) and the Birth and Childhood Office (Office de la Naissance et de l’Enfance) have signed a protocol of cooperation. This facilitates cooperation between youth care workers and the Birth and Childhood Office medical social workers or doctors.

According to Article 12 of the CRC (emphasis added):

‘States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child. […] For this purpose, the child shall in particular be provided the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, either directly, or through a representative or an appropriate body, in a manner consistent with the procedural rules of national law’.

Map 15 presents data on existing provisions on the right of the child to be heard in placement decisions. These include provisions applying in cases of voluntary placements, where there are administrative procedures, in cases of forced placement (without the parents’ consent) and where competent judicial authorities have taken relevant decisions.

Provisions regarding the right of the child to be heard in judicial or administrative procedures on placement in care differ from those establishing the requirement to consider the child’s views when developing an individual care plan. The latter are frequently optional. That is, they are left to the discretion of the social workers and case workers.

The child’s right to be heard is regulated differently in different procedures. This analysis considers the main types of proceedings: (i) adoption; (ii) custody and (iii) criminal proceedings.

Figure 15 – Provisions introducing age requirements on the right of the child to be heard in placement decisions

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have legal provisions introducing age requirements on the right of the child to be heard in placement decisions. Eight Member States have such provisions. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Almost all Member States apply statutory age limitations and take into account factors such as the child’s maturity and ability to express themselves. In some Member States, support from psychologists and social workers accompanies the child’s statement to ensure that it is fully understood.

- Authorities can decide whether or not to hear the child and take their views into account if the age limit is not enshrined in law.

- The weight to be granted to the child’s views differs by case. It depends on an assessment of the child’s age, maturity and understanding.

- When age limits apply, it is often children aged 12+ or 14+ who have to be heard. Whether it applies to younger children remains at the discretion of the authorities.

- Regarding adoption, some Member States require the child’s consent after a certain age. For instance, in Spain, this applies after the age of 12. The child has the right to express their views during the adoption process.

Eight Member States have provisions requiring authorities to listen to children of a certain age: Bulgaria (10), Czechia (12), Spain (12), Croatia (14), Hungary (14), the Netherlands (4), Finland (12) and Sweden (15). In these Member States, whether children younger than these ages have this right largely depends on the authorities. Where no age requirements are in place, it is up to the authorities, for example the judge, the competent court or the administrative body, to assess the child’s maturity and evolving capacities.

In the Netherlands, during investigations of child abuse reports, the investigating team will speak with those affected if they are older than four, the protocol of the Safe at Home organisation states. Those younger than four are only observed.

In France, the juvenile court judge always hears the child, as long as the child is considered capable of discernment. The magistrate has full discretion to decide if the child should be heard.

In Romania, children aged 10 and older need to consent to adoption, according to Law No 273/2004 concerning adoption.

The levels of child participation differ between Member States. At least four Member States – Belgium, Denmark, Poland and Romania – have legal provisions requiring children’s consent or a statement of non-opposition to placement decisions if they are above a certain age (usually 14 or 15).

In almost all Member States, the law provides that children must be heard in proceedings where their interests are at issue, if it does not prejudice their interests or expose them to possible hardship, such as in criminal abuse proceedings. Thus, many Member States have general clauses that allow children to ask to be heard in proceedings affecting them.

For example, in Ireland, the Child Care Act, 1991, as amended by the Children First Act 2015, gives children the right to be heard and to express their views in all matters affecting their welfare. This includes child protection issues.

In Croatia, Article 360 of the Family Act addresses proceedings in which the rights and personal interests of the child are decided, such as adoption. The court will allow children to express their views if the court deems this necessary given the circumstances of the case. Children express their views in a suitable place and with an expert present. Children can revoke their consent to the adoption until the decision on adoption becomes final.

In Italy, children have the right to be heard by competent authorities in judicial proceedings, with the support of psychologists. This ensures the credibility of their statement, that is, that they understand its implications, and the protection of the child. For more information, see Law No 172/2012 and Article 398 of the Italian Criminal Procedure Code.