2. Main challenges for effective forced return monitoring

2.1 Independence

To be effective, monitoring should be carried out by an entity that is sufficiently independent from the authority in charge of returns. The monitors from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees in Germany and those from the Swedish Migration Agency are part of the same entity that is responsible for parts of the return procedure. There is a lack of institutional separation.

Independence issues may also arise in those EU Member States where the monitoring is carried out by national oversight bodies other than human rights institutions, if sufficient safeguards are not in place. Similar risks may emerge where monitoring tasks are set out in contracts with civil society organisations, should these regulate monitoring tasks in a too prescriptive manner or have non-sustainable funding. In these situations, the specific safeguards for independence need to be carefully examined.

Those EU Member States which appointed National Preventive Mechanisms as the body in charge of forced return monitoring offer the strongest guarantees of independence.

2.2 Transparency

An important aspect of effective monitoring is the publication of key findings from the monitoring activities. Most monitoring bodies publish at least a summary of their observations and of their recommendations in regular (usually annual) reports. The Czech Public Defender of Rights and the Portuguese General Inspectorate of Home Affairs also publish an individual monitoring report after each operation.

In some Member States (Austria, Cyprus, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta and Romania), there are no recent public reports on the findings of forced return monitoring activities. In Germany, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees does not publish the findings of its monitoring activities. In Sweden and Slovenia, forced return monitoring bodies informed FRA that reports can be requested.

As a promising practice, the Greek Ombudsman and the National Guarantor for the Rights of Persons Deprived of Liberty in Italy as well as the Diversity Development Group in Lithuania publish regular thematic reports on the return monitoring activities. Where relevant, they also include information on the follow up measures of past recommendations.

2.3 Phases of removal monitored

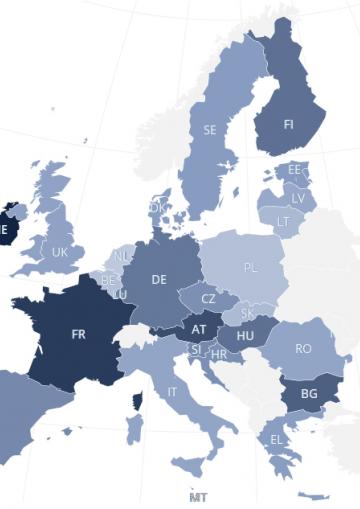

In six EU Member States – Bulgaria, Spain, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia and Poland – the forced return monitoring entity did not monitor any national return operation in 2022, according to the information they provided to FRA. In some other EU Member States, only very few return operations were monitored in 2022, compared to the overall number of forced return operations carried out.

In several EU Member States, based on risk analysis, priority has been given to monitoring the pre-return phase (i.e. the pick-up of returnees, their transfer to the airport, and procedures before and during embarkation). In Cyprus, Czechia and France, the monitoring covered only the pre-return phase, and not the in-flight phase itself, nor the handover of the returnees to their home country authorities. The prioritisation of monitoring the pre-return phase is linked to human and financial resources issues as well as the fact that the pre-departure phase is typically considered one where multiple fundamental rights issues can arise.

Whereas FRA supports a risk analysis-based prioritisation of the monitoring activities, it also considers that at regular intervals all phases of the removal process should be monitored. Otherwise, this may impact on the effectiveness of the forced return monitoring system.

2.4 Types of return operations monitored

Most forced return operations are carried out by air, either through commercial flights or by charter flights. Flights may be organised and funded fully by the national authorities, or they may be coordinated, organised or co-funded by Frontex. National forced return monitoring entities may not always be aware whether a flight which carries returnees only from their own Member State is co-funded by Frontex or not.

For the monitoring of return operations supported by Frontex, a dedicated pool of forced return monitors has been set up within Frontex pursuant to Article 51 of Regulation (EU) 2019/1896. An overview of their work is available in section 1.4 of the Frontex Fundamental Rights Officer’s annual report for 2022. In addition to the Frontex pool of forced return monitors, national monitoring bodies are entitled to monitor their national contingent of returnees on a Frontex flight.

In the first years of their operation, national monitoring bodies focused primarily on monitoring charter flights, where the risk of fundamental rights violations was assessed to be higher, compared to commercial flights. Meanwhile, returns by domestic flights are also monitored.

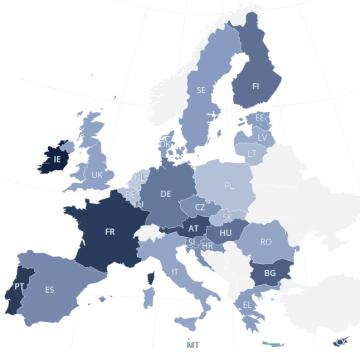

Similarly to 2021, over half of the EU Member States also monitored forced return operations carried out through commercial flights. Although risks during the inflight phase of returns through commercial flights may be lower compared to returns by charter flights, specific issues may emerge in the pre-return phase, particularly when it concerns removals of families or persons with vulnerabilities.

In one out of three EU Member States, return operations by land were monitored in 2022. No return by sea was monitored.

2.5 Funding

Developments over the years show that available funding impacts significantly on the implementation of national monitoring systems. Particularly where it is project-based – as is the case for some EU-funded national monitoring activities – or based on a temporary agreement between the authority and the monitoring entity, an adequate forced return monitoring system may be in place but gaps re-emerge when the funding ends. The duration of contracts with the monitoring body should therefore not be too short and there must be alternative sources for financing forced return monitoring to avoid gaps.