The evolving digital landscape offers a multitude of new opportunities. It can improve communication with, and access to, public services, including health and social care services. [8]Abdi, J., Al-Hindawi, A., Ng, T. and Vizcaychipi, M. P. (2018), ‘Scoping review on the use of socially assistive robot technology in elderly care’, BMJ Open, Vol. 8, e018815; Buyl, R., Beogo, I., Fobelets, M., Deletroz, C., Van Landuyt, P., Dequanter, S., Gorus, E., Bourbonnais, A., Giguère, A., Lechasseur, K. and Gagnon, M. P. (2020), ‘e-Health interventions for healthy aging: A systematic review’, Systematic Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 1, 128.

The European Pillar of Social Rights and the Declaration state that no one should be left behind as society advances (see Chapter 2 Legal and policy instruments at EU and international levels). However, there are risks that the digitalisation of public services may not be accompanied by measures and safeguards that adequately ensure the equal enjoyment of fundamental rights for older persons and other vulnerable groups. [9] Köttl, H. and Mannheim, I. (2021), Ageism & digital technology: Policy measures to address ageism as a barrier to adoption and use of digital rechnology, EuroAgeism Policy Brief, EuroAgeism.

This chapter provides an overview of the demographic and digital situations in the 27 EU Member States (EU-27), North Macedonia and Serbia, and of equal access to public services for older persons.

Based on demographic projections, the 2021 Ageing Report of the European Commission noted that the EU is “turning increasingly grey”. [14]European Commission (2021), The 2021 ageing report: Economic & budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070), Institutional Paper 118, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union (Publications Office), p. 3.

These projections predict a decline in the total population of the EU in the long term and a continuing significant ageing of its population.

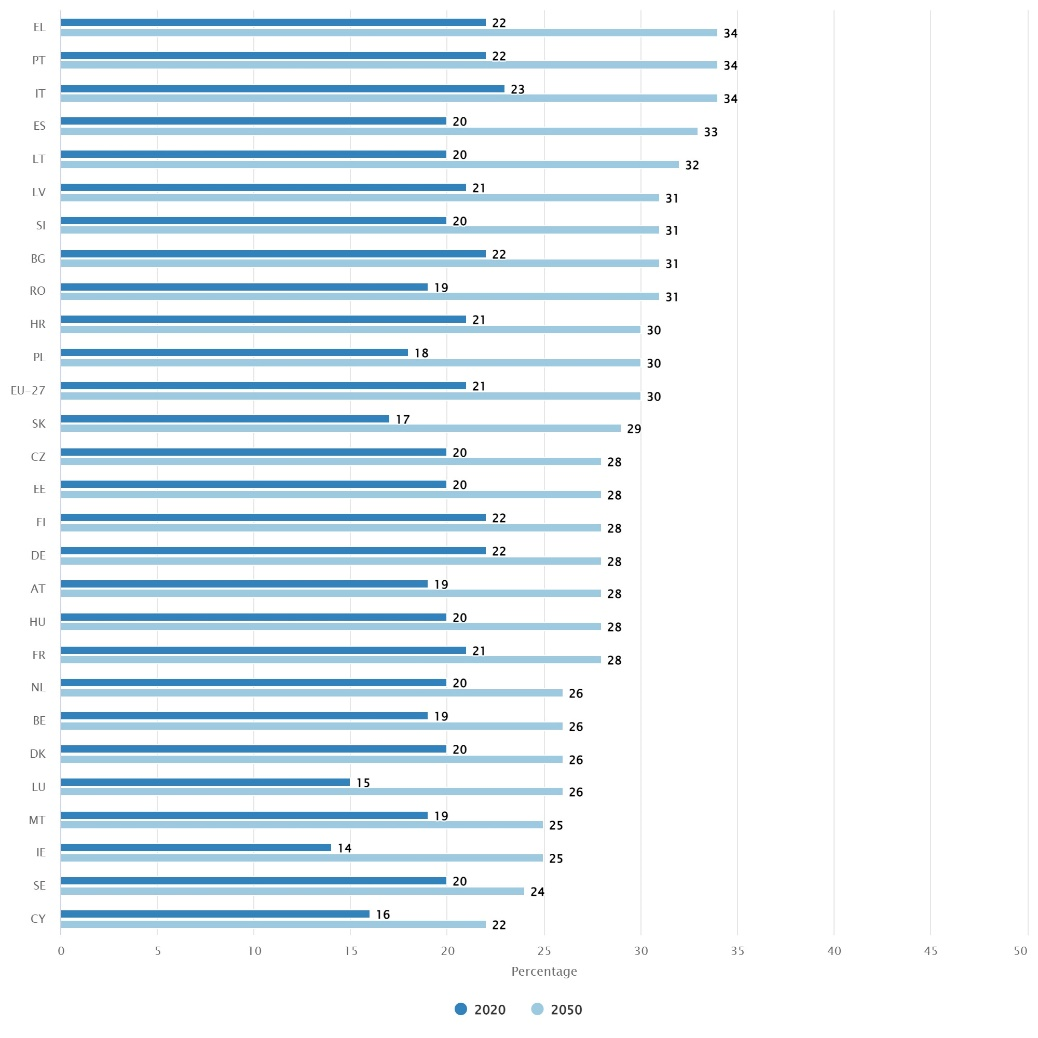

Since the 1950s, EU Member States, like other developed countries, have experienced a continuous ageing of their populations. [15] Długosz, Z. (2011), ‘Population ageing in Europe’, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 19, pp. 47–55. In 2001, 16 % of persons in the EU-27 were 65 or older. [16]Eurostat (2023), ‘Population structure indicators at national level’, online data code: DEMO_PJANIND, accessed 11 January 2023. In 2020, this share rose to 21 %, and it is projected to reach almost 30 % in 2050 (see Figure 1).

The extent and speed of this development vary by Member State. In 2020, the share of persons aged 65 years and more ranged from 25 % in Italy to just below 15 % in Luxembourg and Ireland. [17]Ibid. These differences will increase over time, and in 2050 more than a third of people in Greece, Portugal and Italy are expected to be aged 65 and older, compared with fewer than a quarter in Sweden and Cyprus (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – People aged 65 and older in the EU-27 in 2020 and projected for 2050 (% of total population)

Source: FRA (2023), based on Eurostat (2020), ‘Data browser – Demographic balances and indicators by type of projection’, online data code: PROJ_19NDBI, accessed 23 January 2023

Population ageing is driven by low birth and mortality rates, across EU Member States, as over the last 50 years women have had fewer children and given birth later in life. Migration patterns also affect age structures, for instance if younger or retired persons have moved to other Member States or emigrated outside the EU or if young refugees and immigrants have settled in some Member States more often than others. [18]European Commission (2021), The 2021 ageing report: Economic & budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070), Institutional Paper 118, Luxembourg, Publications Office; Eurostat (2020), Ageing Europe – Looking at the lives of older people in the EU, Luxembourg, Publications Office; European Commission (2023), The impact of demographic change in a changing environment, Luxembourg, Publications Office.

Europeans live longer and experience more years in good health, because of better healthcare, among other reasons. In 2021, a 65-year-old in the EU could expect to live for another 19.3 years on average. That number is less for men (17.3 years) than for women (20.9 years). [19]Eurostat (2023), ‘Life expectancy at age 65, by sex’, online data code: TPS00026, accessed 11 January 2023.

Furthermore, the number of healthy life years that one could expect at the age of 65 in 2020 is 9.8 years: 9.5 for men and 10.1 for women. [20] Eurostat (2023), ‘Healthy life years at age 65 by sex’, online data code: TEPSR_SP320, accessed 11 January 2023.

In 2050, projections foresee that 65-year-old men will have a life expectancy of 18.8 more years in Bulgaria, and up to 22.6 more years in France. Women of the same age can expect to live for 22.3 more years in Bulgaria, and 26.5 more years in France. [21] Eurostat (2023), ‘Projected life expectancy by age (in completed years), sex and type of projection’, online data code: PROJ_19NALEXP, accessed 11 January 2023.

Because of this demographic shift, the old-age dependency ratio is projected to increase significantly. This ratio calculates how many persons of working age (20 to 64 years) are available to work to cover the care and pension costs of an older person aged 65 and more. In the EU, the old-age dependency ratio rose within the past 20 years from just over one older person to four working-age adults in 2001 to just over one to three in 2019. By 2050, less than two working-age adults per older person will be available to finance care and pension costs. [22] Eurostat (2020), Ageing Europe – Looking at the lives of older people in the EU, Luxembourg, Publications Office.

This will significantly increase costs, especially in the long run, mainly of healthcare and pensions. The main policy debates therefore revolve around the financial impact of population ageing. One policy option is to increase the retirement age. This provokes resistance but is already implemented or planned in most Member States. Other options include measures to develop active and healthy ageing. [23]European Commission (2021), The 2021 ageing report: Economic & budgetary projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070), Institutional Paper 118, Luxembourg, Publications Office.

In the 21st century, digital technologies and services have become core elements of everyday life, including for public administrations and services. The European Digital Decade (2020 to 2030) provides a vision for a digital Europe and sets targets monitored by the DESI to ensure that fundamental and social rights are respected online in the same ways as offline. [24] European Commission (2021), 2030 digital compass: The European way for the Digital Decade, COM (2021) 118 final, Brussels, 9 March 2021.

While many have benefited from using information and communication technology (ICT), not everyone has the same motivation, opportunities and skills to access and use it. [25] van Dijk, J. A. (2006), ‘Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings’, Poetics, Vol. 34, Nos. 4–5, pp. 221–235.

Digital inequalities reflect and can even exacerbate social inequalities for those lacking access to the internet or digital skills.

For instance, people with low incomes can be digitally excluded, for example from using digital public or private services, as they may not have the means to pay for the necessary devices, internet access or support. It is often assumed that support comes from the social environment, such as family members or friends, which is not always the case. Consequently, some people or groups profit more from digital opportunities because they have earlier and better access to ICT or support. In the COVID-19 crisis, digital inequality was of particular concern for older persons and people with lower education levels or health problems. [26] van Dijk, J. (2020), The digital divide, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Polity; Eurofound (2023), Economic and social inequalities in Europe in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, Luxembourg, Publications Office; Holmes, H. and Burgess, G. (2022), ‘Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online’, Digital Geography and Society, Vol. 3, 100041; Imran, A. (2022), ‘Why addressing digital inequality should be a priority’, Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, Vol. 89, No. 3, e12255; van Deursen, A. J. (2020), ‘Digital inequality during a pandemic: Quantitative study of differences in COVID-19-related internet uses and outcomes among the general population’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 22, No. 8, e20073; Scheerder, A. J., van Deursen, A. J. and van Dijk, J. A. (2019), ‘Internet use in the home: Digital inequality from a domestication perspective’, New Media & Society, Vol. 21, No. 10, pp. 2099–2118.

The digital divide is understood as the division between people with access to and use of ICT, and the necessary skills, and those without. It is framed primarily in terms of (in)equalities. Clearly, the availability and advancement of ICT has brought enormous advantages and reduced social inequalities for many people who become motivated to use new technologies, have physical access and master the necessary basic skills. With the propagation of the use of ICT, the related costs will decrease, and access to low-cost or free and easy-access information will be affordable for previously excluded groups too. [27] van Dijk, J. (2020), The digital divide, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Polity.

The most often used categorisation of the digital divide uses three levels.

The first-level digital divide concerns physical access to ICT. In 2022, 92 % of all households in the EU-27 had internet access at home, a rapid increase from 75 % in 2012. [28]Eurostat (2023), ‘Level of internet access – Households’, online data code TIN00134, accessed 28 March 2023.

The second-level digital divide relates to ICT use and the skills needed. In 2022, 91 % of people aged 16 to 74 years had used the internet in the previous 12 months, and 7 % had never used the internet. [29] Eurostat (2023), ‘Internet use by individuals’, online data code TIN00028, accessed 28 March 2023.

In 2021, 54 % of 16- to 74-year-olds had basic or above basic overall digital skills. [30]Eurostat (2023), ‘Individuals with basic or above basic overall digital skills’, online data code: ISOC_SK_DSKL_I21, accessed 28 March 2023.

The third-level digital divide concentrates on outcomes and usage. Interaction with public services, for instance related to tax declarations or pension rights, through the internet can be used as an indicator. In 2021, 59 % of 16- to 74-year-olds had used the internet for interaction with public authorities in the previous 12 months. [31]Eurostat (2023), ‘Internet use by individuals for interaction with public authorities’, online data code: TIN00012, accessed 28 March 2023.

These EU-level statistics, with significant variations between Member States, show that the first-level digital divide is closing. However, the rapid development of new generations of technical devices might still leave a substantial gap. While there is progress on the second-level divide, with an increase in internet use, the gap related to digital skills remains large, as does the gap on the third level. Behind these divides are social and digital inequalities, often linked to specific groups or socio-demographic backgrounds. [32] Imran, A. (2022), ‘Why addressing digital inequality should be a priority’, Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, Vol. 89, No. 3, e12255.

The concept of the ‘grey digital divide’ focuses on the digital disadvantages of older persons. [33] van Dijk, J. (2020), The digital divide, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Polity; Hargittai, E. and Dobransky, K. (2017), ‘Old dogs, new clicks: Digital inequality in skills and uses among older adults’, Canadian Journal of Communication, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 195–212.

Research shows that the major challenges for older persons in the digital world are participation and communication through networks, or in the healthcare environment. [34] Mubarak, F. and Suomi, R. (2022), ‘Elderly forgotten? Digital exclusion in the information age and the rising grey digital divide’, INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, Vol. 59; Lopez de Coca, T., Moreno, L., Alacreu, M. and Sebastian-Morello, M. (2022), ‘Bridging the generational digital divide in the healthcare environment’, Journal of Personalized Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 8, 1214.

In addition, any progress made by people aged 75 and older in mastering essential digital skills and using the internet in different environments or subject areas is not monitored through the DESI, as the official data collection ends at the age of 74.

The ‘grey digital divide’ refers to the obstacles that older persons encounter in terms of access, skills and opportunities. [35] Alexopoulou, S., Åström, J. and Karlsson, M. (2022), ‘The grey digital divide and welfare state regimes: A comparative study of European countries’, Information Technology & People, Vol. 35, No. 8, pp. 273–291.

As all persons are entitled to access public services whatever their age, access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation is used as an example of the fundamental rights challenges of older persons in digital societies.

The following analysis uses Eurostat data that provide information about the age groups 55 to 64 and 65 to 74. For a more detailed analysis, the two groups can be combined. Eurostat’s statistics on the digital economy and society do not cover people aged 75 years and older.

There are further divides within the grey digital divide, [36] Friemel, T. N. (2016), ‘The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors’, New Media & Society, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 313–331.

apparent in the two age groups used by Eurostat, as members of older generations have been exposed to digitalisation in different ways and at different times, for example in the workplace or at younger ages. For persons aged 75 years and older, it can only be assumed that the barriers in the digital world are even higher, as some results from FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey show. [37] FRA (2020), ‘Selected findings on age and digitalisation from FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey’, background paper for the online conference Strengthening older people’s rights in times of digitalisation – Lessons learned from COVID-19, 28–29 September 2020.

Education is a supportive factor for digital skills, but also interlinked with other socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, income, background of parents, area of domicile, migration background and race. It often can be used as proxy for socio-economic status, if more detailed data or information is missing.

At all ages, education is a strong asset in a digitalising world. People with higher educational outcomes are more at ease in the digital world than those with lower levels of education, all the results in this report show. In the last few decades, the share of older persons, aged 55 to 74, who had attained at most a low education level (International Standard Classification of Education levels 0–2) decreased by more than 20 percentage points in the EU-27, from 55 % in 2004 to 32 % in 2021. At the same time, the share of older persons with high education levels (International Standard Classification of Education levels 5–8) increased to 22 %, 10 percentage points more than in 2004. However, the results varied widely across Member States in 2021, from fewer than 10 % of older persons having low education levels in Lithuania, Latvia and Czechia to more than 50 % in Spain, Italy, Malta and Portugal. [38] Eurostat (2023), ‘Population by educational attainment level, sex and age’, online data code: EDAT_LFS_9903, accessed 28 March 2023.

The most impressive change concerns the closing of the gender gap in education for 55-to-74-year-old women. In 2021, only slightly more older women than older men (34 % to 29 %) finished their education at a low level, while the gender gap for medium and high education levels closed further by two to three percentage points. Going forward, women will on average be better educated than men. [39]Ibid.

However, even with all this progress, nearly one out of three older persons in the EU-27 may still face difficulties in the digital sphere due to low educational achievements.

In 2019, the reasons provided most frequently for not having internet access at home were the high cost of access (23 %), equipment (25 %) or both (32 %), together with lack of skills (45 %) and lack of interest (45 %). [40] Eurostat (2023), ‘Households – Reasons for not having internet access at home’, online data code: ISOC_PIBI_RNI, accessed 28 March 2023.

These answers were provided at household level, by persons aged 16 to 74 years, but it can be assumed to also reflect the situation of the 28 % of older persons aged 65 to 74 years who in 2021 had never used the internet. [41] Eurostat (2023), ‘Individuals – Internet use’, online code ISOC_CI_IFP_IU, accessed 26 June 2023.

Therefore, as the first digital divide relating to internet coverage and physical access in the EU-27 is closing, the motivation for using the internet and the necessary skills have become more relevant for the digital inclusion of older persons.

In terms of equipment, older persons increasingly use mobile devices for the internet – 81 % of 55- to 64-year-olds and 60 % of 65- to 74-year-olds in 2021 - even though 33 % and 24 %, respectively, also still use a desktop computer or other devices. [42] Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals – Devices used to access the internet’, online data code: ISOC_CI_DEV_I, accessed 6 January 2023.

These findings underline the importance of device-agnostic software or data that have been designed to work across a range of devices rather than just one, especially for applications that public services use.

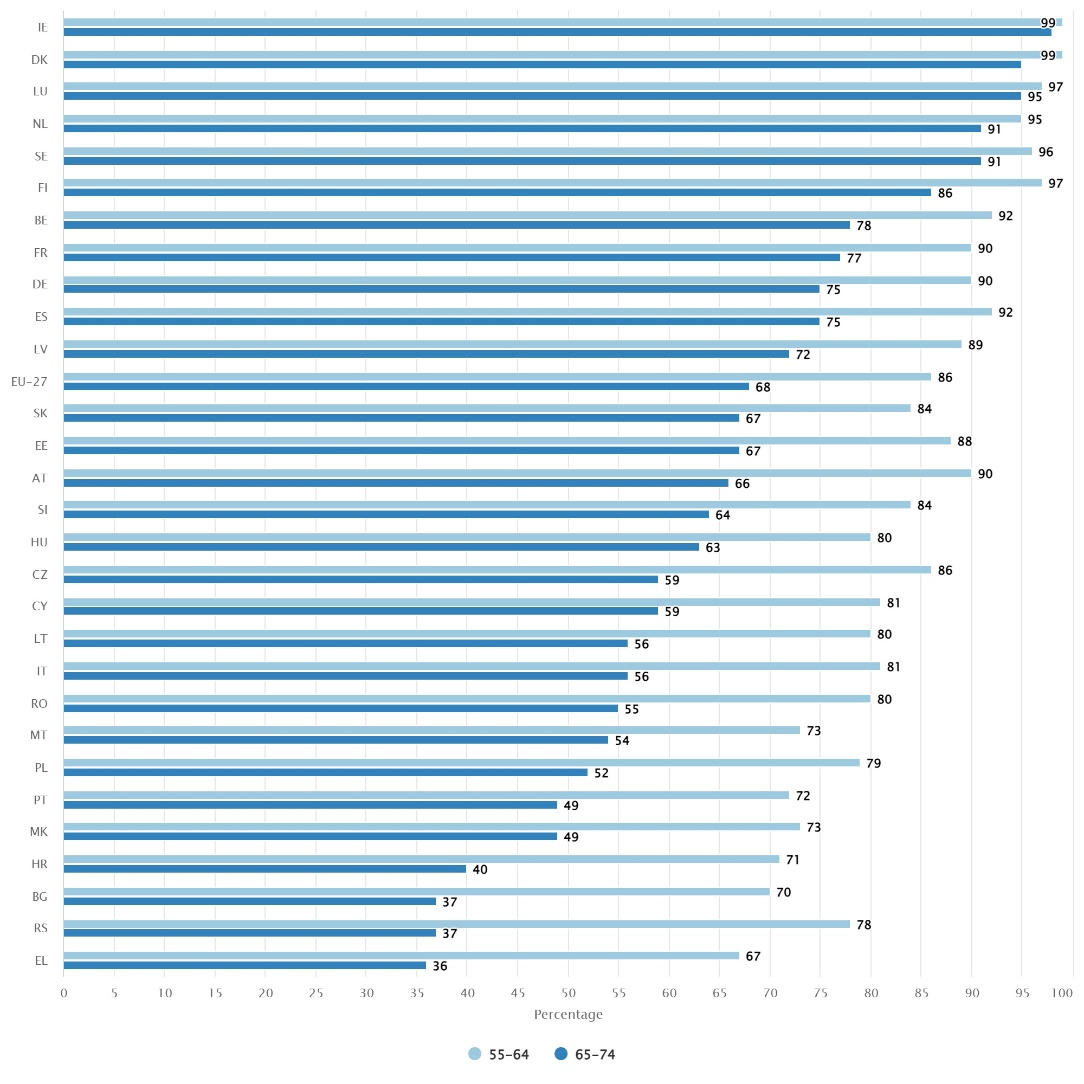

Between 2011 and 2021, the share of 55- to 74-year-old people in the EU-27 who had used the internet in the previous 12 months increased from 42 % to 78 %. Progress was visible in all Member States, North Macedonia and Serbia, with country-specific variations. The grey digital divide is very visible in internet use in 2021 (Figure 2): 86 % of people aged 55 to 64 years used the internet in 2021, compared with 68 % of those aged 65 to 74 years. [43] Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals – Internet use (last internet use in the last 12 months)’, online data code: ISOC_CI_IFP_IU, accessed 6 January 2023.

In some Member States with very high general user rates, this gap is nearly closed. For instance, in Ireland, Denmark and Luxembourg, between 99 % and 95 % of people aged 16 to 74 years, 55 to 64 years or 65 to 74 years had used the internet in the previous 12 months. However, in other countries with high general user rates (90 to 95 %) the difference in internet use between people aged 55 to 64 years and 65 to 74 varies between 13 percentage points in Belgium and France and 23 percentage points in Austria. [44]Ibid.

Figure 2 – Older persons having used the internet in the last 12 months, 2021 by age group (%)

Source: FRA (2023), based on Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals – internet use’, online data code: ISOC_CI_IFP_IU, accessed 6 January 2023

Across all EU Member States, North Macedonia and Serbia, the share of persons aged 55 to 64 who have used the internet in the last 12 months ranges from 67 % in Greece to 99 % in Ireland, and that of those aged 65 to 74 ranges from 36 % in Greece to 99 % in Ireland. The biggest differences between the two age groups are in Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and Croatia, at 30 to 40 percentage points. [45]Ibid.

In 2021, 96 % of persons aged 55 to 74 with high education levels had used the internet in the previous 12 months, compared with 61 % with low education levels. In all Member States and candidate countries, at least 85 % of highly educated older persons were internet users, and at least 19 % of older persons with low levels of education. However, in the last 10 years the share of older persons with low educational attainment using the internet in the EU-27 has tripled. And in about half of the Member States and candidate countries, at least 50 % of people aged 65 to 74 with low education levels have used the internet in the last 12 months. [46]Ibid.

The findings reflect the differences in the advancement of the digitalisation of societies, the generational differences in the motivation to embrace new technologies and splits in the grey digital divide. It can be assumed that, for people aged 75 years and more, the situation is even worse than for 65- to 74-year-olds.

As outlined in the DESI report of 2022, “Insufficient levels of digital skills hamper the prospects of future growth, deepen the digital divide and increase risks of digital exclusion as more and more services, including essential ones, are shifted online.” [47] European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022: Thematic chapters, Brussels, pp. 7–8, available at ‘Download European Analysis 2022 (.pdf)’. For 2030, the Digital Decade has a target of 80 % of adults (aged 16 to 74 years) having at least basic digital skills. The related indicator covers five areas (information and data literacy; communication and collaboration; digital content creation; safety; problem solving), each with a list of various activities. [48] European Commission, EU Science Hub (n.d.), ‘DigComp framework’. To have at least basic digital skills, at least one activity in each area has to be mastered.

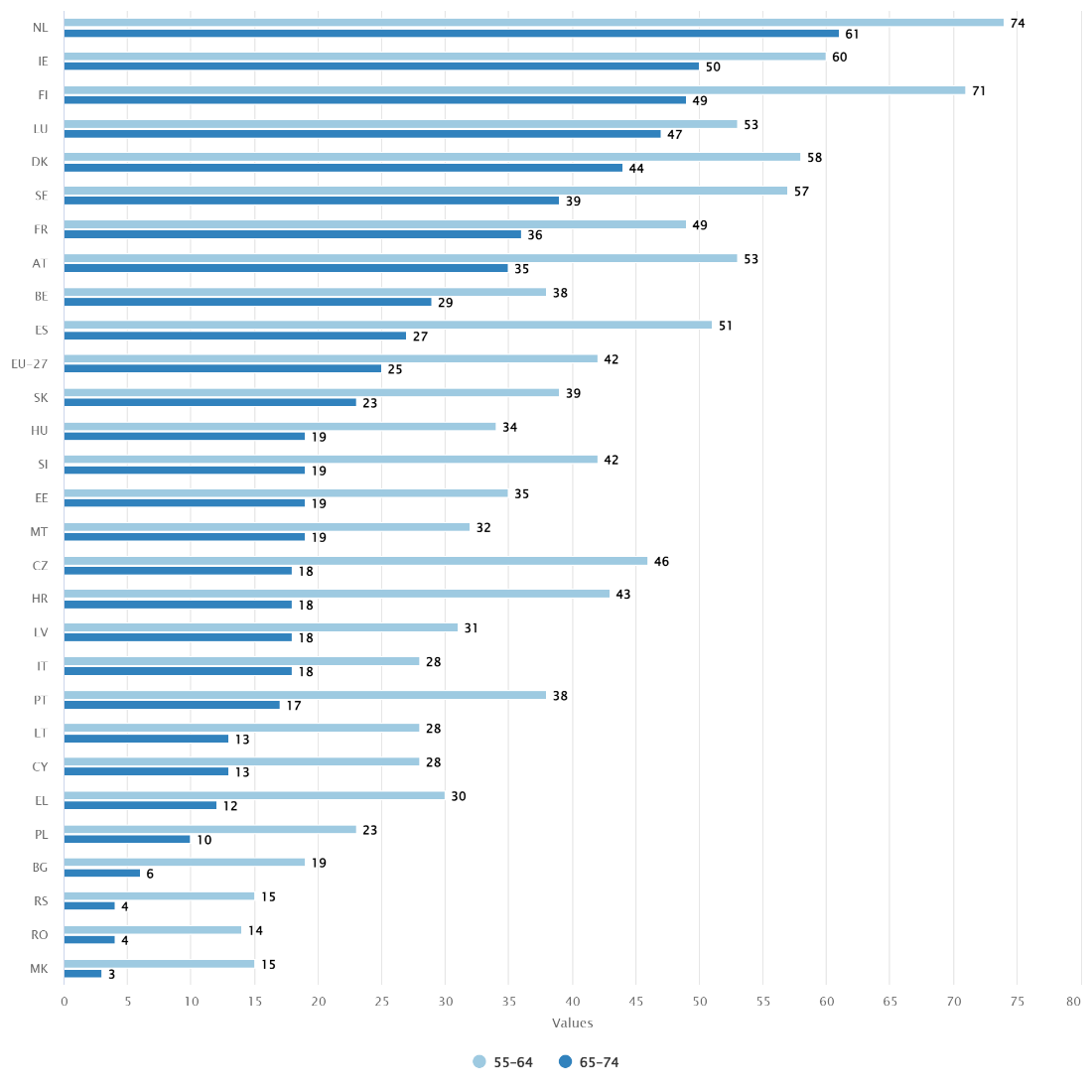

Figure 3 – Older persons with at least basic digital skills, by Member State and age group, 2021 (%)

Source: FRA (2023), based on Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals’ level of digital skills (at least basic or above basic skills)’, online data code: ISOC_SK_DSKL_I21, accessed 6 January 2023

In 2021, 42 % of 55- to 64-year-olds and 25 % of those aged 65 to 74 had at least basic digital skills, with major differences at Member State level (Figure 3). In the Netherlands and Finland, more than 70 % of people aged 55 to 64 years had at least basic digital skills; in North Macedonia, Serbia and Romania, 15 % or fewer did. In comparison, 65- to 74-year-olds had basic skills considerably less often, between 50 % in Ireland and fewer than 5 % in Serbia, Romania and North Macedonia, not considering the outstanding 61 % in the Netherlands. Reflecting the results for internet use, a strong gap exists, with only one out of four people aged 65 to 74 having the necessary skills to participate in digitalising societies (Figure 3).

Slightly more men (39 %) than women (31 %) aged 55 to 74 have at least basic digital skills. The higher the education level, the more older persons have the necessary digital knowledge – only 15 % of people with a low level of education compared with 66 % of highly educated people. [49] Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals’ level of digital skills (at least basic or above basic skills)’, online data code ISOC_SK_DSKL_I21, accessed 6 January 2023.

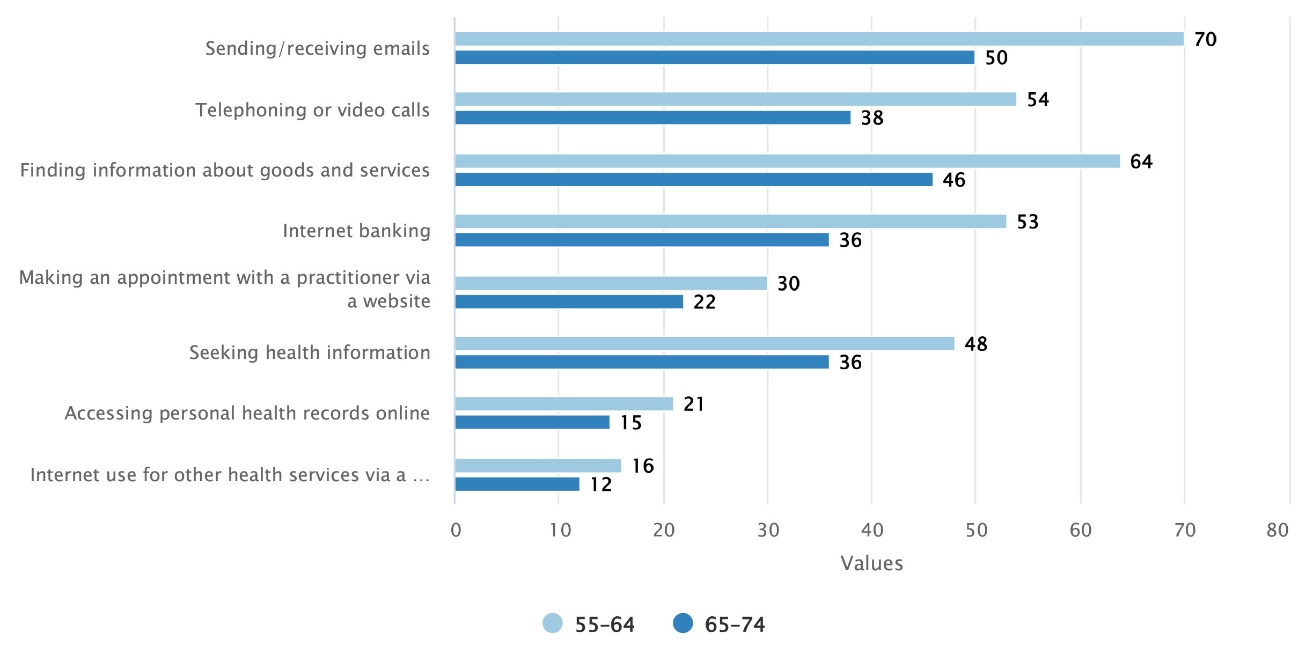

Older persons use the internet in different ways. Sending emails and looking for information are frequent digital activities among both age groups under consideration, followed by telephone and video calls and internet banking. A large share of 55- to 64-year-olds (53 % to 70 %) use the internet for these activities, while only 36 % to 50 % of 65- to 74-year-olds do (Figure 4).

Access to health information and records is important for older persons, but only a few use the internet for this. However, this also depends on the digital offers from health providers. Some 48 % of 55- to 64-year-olds use the internet to seek health information, compared with 36 % of the older age group. Only 15 % of 65- to 74-year-olds access health records online, and 22 % organise appointments with practitioners using the internet, while 55- to 64-year-olds use the internet for these activities slightly more often (21 % and 30 %) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Online activities by older persons in 2022 in the EU-27, by age groups (%)

Source: FRA (2023), based on Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals – internet activities’, online data code: ISOC_CI_AC_I, accessed 22 January 2023

Overall, older persons are increasingly using the internet and learning digital skills. Older women aged 55 to 74 use the internet slightly more for social networking and for health information than men, but less for online banking. [50] Eurostat (2022), ‘Individuals – internet activities’, online data code ISOC_CI_AC_I, accessed 25 July 2023. Given the great differences between older persons, not all are at risk of digital exclusion, as a significant share of older persons actively use digital technologies.

The possibility of using digital public services instead of physical access can be a good alternative for some groups of older persons. However, if the service is only offered online, people without internet access, the necessary skills or people who can support them will find it challenging to use these services.

In 2021, 53 % of people aged 55 to 64 and 38 % of those aged 65 to 74 had been in contact with public services using the internet in the previous 12 months. The higher the education level, the more often people aged 55 to 74 interacted digitally with public services. For example, 76 % of older persons with a high level of formal education interacted through the internet with public services, compared with 26 % with low educational attainment. Men (50 %) use this type of interaction slightly more often than women (43 %). [51] Eurostat (2022), ‘E-government activities of individuals via websites (Internet use: interaction with public authorities (last 12 months))’, online data code ISOC_CIEGI_AC, accessed 25 July 2023.

Among internet users, 39 % of 55- to 64-year-olds and 27 % of 65- to 74-year-olds used the internet in 2021 to submit a completed form to public services in the last 12 months. Persons aged 55 to 74 with a high educational level (61 %) more often than with low levels (30 %), and slightly more men (47 %) than women (40 %). [52] Eurostat (2022), ‘E-government activities of individuals via websites (Internet use: submitting completed forms (last 12 months)’, online code: ISOC_CIEGI_AC, accessed 25 July 2023.

People aged 55 to 74 constitute a large and growing part of the population and contribute to achieving the 2030 targets of the Digital Decade. One of these targets is that 80 % of 16- to 74-year-olds should at least have basic digital skills. But with three out of four older persons not having the skills considered necessary for basic online activities, the target might not be achieved, and a substantial group will be at risk of digital exclusion. These persons will be at risk of having their right to equal access to public services violated.

The following chapters will analyse the extent to which legal and policy frameworks, measures and programmes protect the rights of older persons and other groups at risk of digital exclusion, to support them to participate fully in societies that are digitalising.