Victims of ill-treatment at borders are in a vulnerable situation. Victims rarely report such incidents to law enforcement authorities. In France, for example, a civil-society organisation has said that only 1 in 10 cases reported to them in Calais leads to the filing of a complaint [19] Written contribution by a French civil-society organisation, October 2023. .

Reasons for not reporting appear manyfold. The lawyers and civil-society organisations consulted for this report give the following examples of reasons: a fear of reprisals, distrust in the authorities, victims’ lack of willingness (as the priority is to regularise their stay in Europe), a fear of potential negative impacts on the asylum procedure, smugglers’ advice not to report incidents and disbelief that reporting would bring any tangible benefit.

As an illustration, a Romanian civil-society organisation reported that victims believe that investigative procedures would not lead to any result for various reasons. These include difficulties in presenting solid evidence of the violation or in identifying the location of the incidents and the authority involved.

In France, a civil-society organisation active in Calais that was contacted for this research noted that the French police inspection service discouraged them from reporting incidents. This is because their volunteers are not present during the incident and cannot testify and the migrants are either not available or not willing to testify [20] Written contribution by a French civil-society organisation, October 2023. .

In Greece, the Ombudsman stressed victims’ and witnesses’ fear of coming forward and being involved in official proceedings against law enforcement authorities, as they are in a vulnerable position [21] Greek Ombudsman, ‘Third party intervention by the Greek Ombudsman to the European Court of Human Rights in relation to applications Nos 15067/21 (G. R. J. v Greece) and 15783/21 (A. E. v Greece)’ (‘Δελτίο Τύπου | Παρέμβαση τρίτου του Συνηγόρου του Πολίτη κατόπιν πρόσκλησης του ΕΔΔΑ για το ζήτημα των επαναπροωθήσεων’), 26 March 2024, p. 7. .

In some cases, non-EU nationals may report violations anonymously, but this makes it difficult to investigate them, as victims or witnesses cannot be heard. In Romania, for example, in 2020 and 2021, asylum applicants reported some incidents. This led to an internal investigation by the General Inspectorate of Border Police, which concluded that it was impossible to identify alleged perpetrators. None of the asylum applicants was willing to submit a criminal complaint [22] Information provided by a Romanian civil-society organisation in October 2023. Investigations can be carried out under the mechanism for reporting incidents at the borders established under the memorandum of understanding between General Inspectorate for Border Police and UNHCR. For public information about the memorandum see AIDA (Asylum Information Database), Country Report: Romania – 2022 update, 2023, p. 26. .

Some legal measures discourage reporting further. In Cyprus, according to a legal amendment adopted in May 2024, knowingly making false statements to the Independent Authority for the Investigation of Allegations and Complaints Against the Police in relation to ‘imaginary offences’ is a criminal offence. This offence is punishable by imprisonment of up to 1 year and/or a fine of up to EUR 2 000 [23] Cyprus, Official Gazette of the Republic of Cyprus, ‘L. 73 (I)/2024 on Police (Independent Authority for the Investigation of Allegations and Complaints Against the Police) (amendment)’ (‘Ν. 73(I)/2024 – Ο περί Αστυνομίας (Ανεξάρτητη Αρχή Διερεύνησης Ισχυρισμών και Παραπόνων) (Τροποποιητικός) Νόμος του 2024’), 2024. .

To file complaints, before either the judicial authorities or other bodies, victims need clear information and support from professionals. A common reason not to report is a lack of awareness of how to submit complaints and access justice [24] See ENNHRI (European Network of National Human Rights Institutions), Strengthening Human Rights Accountability at Borders, Saint-Gilles, Belgium, 2022, p. 13. .

Under-reporting is a broader phenomenon not limited to incidents at borders, as FRA’s fundamental rights survey shows. With respect to the most recent incident they had experienced in the past 5 years, victims reported to the police only 30 % of incidents involving physical violence and 11 % of those involving harassment [25] FRA, Crime, Safety and Victims’ Rights – Fundamental rights survey, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2021, Chapter 4. .

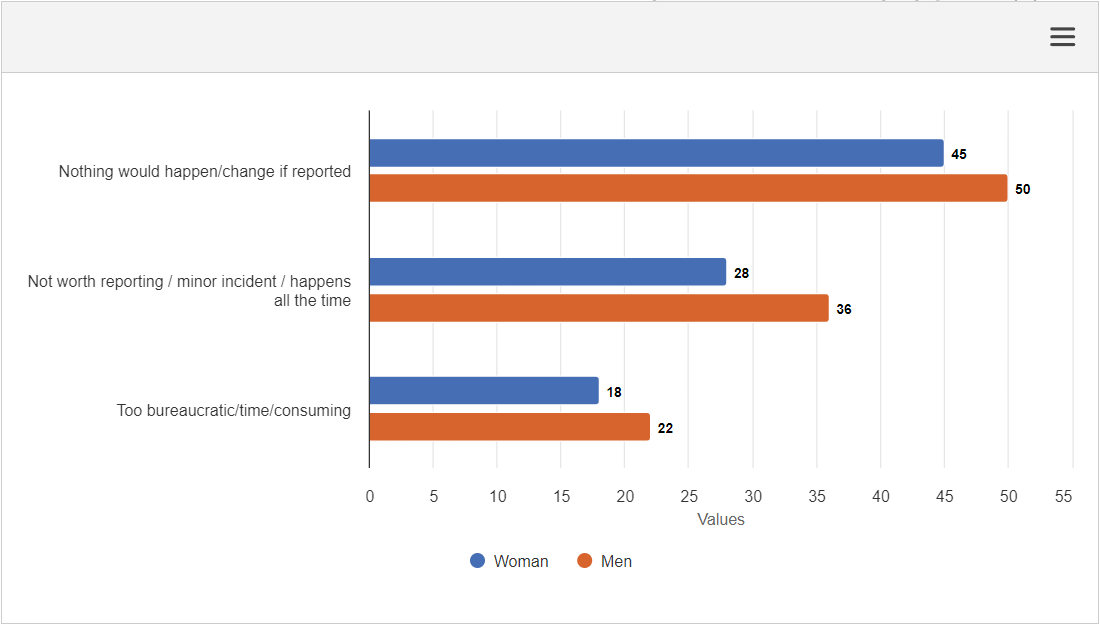

The phenomenon of under-reporting also concerns hate crimes and bias-motivated harassment [26] FRA, Encouraging Hate Crime Reporting – The role of law enforcement and other authorities, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2021. . As an illustration, people of African descent who FRA interviewed in 13 Member States said that they did not report racist incidents to the authorities as nothing would change. Other top reasons relate to their view that such incidents happen all the time and are minor or not worth reporting and that they consider reporting to be time-consuming or bureaucratic (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Experiences of people of African descent – top three reasons for not reporting the most recent incident of racist harassment to authorities or services in the 5 years before the survey, by gender (%)

Notes: Out of all respondents of African descent who experienced racist harassment in the 5 years before the survey and did not report it anywhere (women, n = 882; men, n = 953); weighted results, sorted by the category ‘women’. Question: ‘Why did you not report the incident (i.e. racist harassment experienced in the 5 years before the survey (or since you have been in [country])) or make a complaint to the police or any other organisation?’

Alternative text: Bar chart showing that the main reasons why people of African descent do not report incidents of racist harassment are that nothing would change (45 % of men and 50 % of women); it is not worth reporting, as it happens all the time (28 % of men and 36 % of women); and that it is too bureaucratic and time-consuming (18 % of men and 22 % of women).

Source: FRA’s EU survey on immigrants and descendants of immigrants, 2022, as reproduced in FRA, Being Black in the EU – Experiences of people of African descent, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, Figure 27.

Whistle-blowers can significantly contribute to a well-functioning accountability system, if afforded adequate protection. Some Member States have established in their laws the possibility for whistle-blowers to report breaches of criminal law and other ethical misconduct committed by public officials [27] FRA, Addressing Racism in Policing, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2024, p. 7. .