3. Main findings from the monitoring activities

Overall, escort officers have demonstrated professionalism, effective use of de-escalation techniques and made less use of coercive measures. For example, in the Netherlands, the national monitoring body found that the use of handcuffs during return transfers was significantly reduced in 2022.

Positive developments also concerned improved waiting premises in airports (for example as observed at the Berlin, Dusseldorf, Frankfurt, Leipzig and Munich airports in Germany) with separate areas, adapted to the needs of families and children.

National monitoring bodies also continue to highlight in their reports several deficiencies, as observed during on-site monitoring activities in 2022.

A recurrent issue is the lack of capacity of national monitors in terms of human resources and funding. This is also showcased by the low number of monitored operations in 2022, particularly during the in-flight and hand-over phase.

Shortages in interpretation services are also repeatedly pinpointed. In this context, for Frontex-supported operations, the Frontex Fundamental Rights Officer stressed the need to introduce a requirement to have at least one interpreter on each return operation. A persisting issue in Czechia concerns the obstacles monitors encounter in entering police escort vehicles during the transfer of returnees.

Despite positive developments, issues concerning the identification of vulnerabilities continued to be reported. Monitoring bodies have recorded instances where escort officers were not informed on the specific needs of persons with health problems, disabilities, or pregnancy. The Greek Ombudsman noted inefficient “fit-to-fly” medical pre-screenings, in the form of a last-minute interview or an assessment conducted without interpreters.

Concerning the return of families with children, several monitoring entities, including the National Preventive Mechanism in Germany, raised concerns about the negative effects on children’s well-being resulting from family separation, unannounced nighttime pickups, witnessing of stressful or violent scenes and the use of children as de facto interpreters.

As regards the use of coercive measures against returnees, these can be used only as a measure of last resort, in line with the principles of necessity and proportionality. However, handcuffing is applied preventively to all returnees in France, while the use of wrist restraints is general practice in Italy. In Munich (Germany), the complete documentation of coercive measures used provides for increased transparency, as the German National Preventive Mechanism noted.

Concerns regarding the provision of adequate and necessary information to returnees is also mentioned in national monitoring reports. In Lithuania, for example, returnees were not informed in a timely manner about the flight details, and thus could not prepare accordingly. In addition, the Belgian General Inspectorate of the Federal Police and the Local Police raised concerns about the lack of information provided to returnees on their right to complain. Language barriers significantly impeding the right to information were also reported by the Czech Ombudsperson.

Following the Council of Europe’s Twenty guidelines on forced returns, EU Member States should involve more same-sex employees, including interpreters, to provide a gender-sensitive handling of returns. However, the policy of using same-sex officers and medical staff has not been followed in many EU Member States yet.

Lastly, as regards material support, several monitoring bodies mentioned that returnees in need were not provided with petty cash for necessary purchases during the forced return operation. The Lithuanian monitoring entity has suggested giving returnees pocket money and a travel allowance to enable the safe return from the airport of destination to their place of residence.

In 2022, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) published two reports on the monitoring of preparations and conduct of a joint return operation by air organised by the Belgian and Cypriot authorities and coordinated by Frontex. In its report on the visit to Belgium, the CPT mentions that it did not receive allegations of ill-treatment but that there is a need to strengthen the procedural safeguards against non-refoulement, including by implementing a “last call procedure” before handover. As regards Cyprus, the CPT noted that returnees were treated respectfully but that it received allegations of ill-treatment occurring after past aborted removal attempts. Therefore, the CPT recommended that the authorities take the necessary steps to ensure that medical evidence of ill-treatment is collected by carrying out a medical examination before departure and on return to the detention centre after aborted removals. It also made specific recommendations on the need for timely notification of removal, access to legal aid and medical examination including the issuance of a “fit-to-fly” certificate.

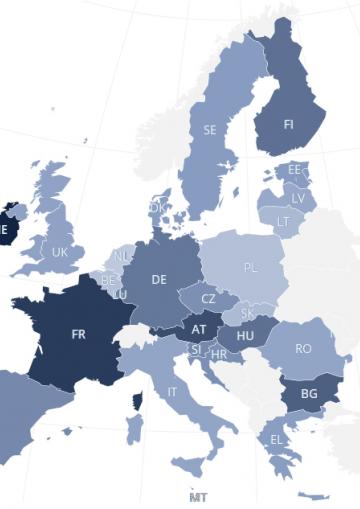

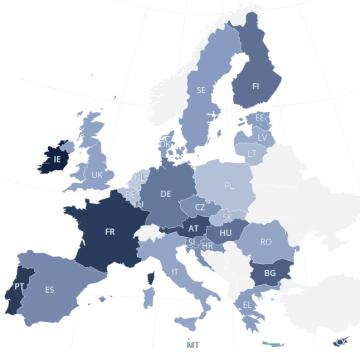

Annex: Operation of forced return monitoring in 2022 in 27 EU Member States