Current migration situation in the EU: separated children

Although official figures on the phenomenon are lacking, it is clear that children arriving in the European Union (EU) are often accompanied by persons other than their parents or guardians. Such children are usually referred to as ‘separated’ children. Their identification and registration bring additional challenges, and their protection needs are often neglected. On arrival, these children are often ‘accompanied’, but the accompanying adult(s) may not necessarily be able, or suitable, to assume responsibility for their care. These children are also at risk of exploitation and abuse, or may already be victims. Their realities and special needs require additional attention. The lack of data and guidance on separated children poses a serious challenge.

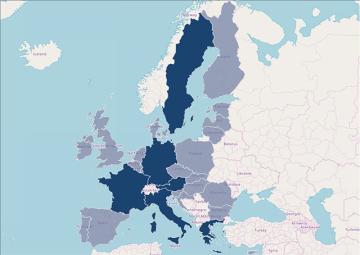

FRA evidence – as of December 2016 – indicates that Member States do not collect data on separated children, and relevant information is very scarce. Separated children are legally considered unaccompanied children, though in practice their treatment may differ. This reality – and the general lack of guidance – makes it challenging to establish how Member States respond to these cases. Practice may also vary depending on the region or city, and from case to case.

Separated children are children who have been separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary care-giver, but not necessarily from other relatives. These may, therefore, include children accompanied by other adult family members. The accompanying adult(s), who could also be unrelated, may not necessarily be able to, or suitable for, assuming responsibility for their care.

In contrast, EU law defines unaccompanied children as children who arrive unaccompanied by an adult responsible for them, whether by law or practice of the Member State concerned, and for as long as they are not effectively taken into the care of such a person; it includes children who are left unaccompanied after they enter the territory of a Member State. The legal status of separated children does not differ, but they form a special sub-group of children among the unaccompanied ones that requires specialised protection.

The treatment of children in both categories – separated and unaccompanied – should be similar, despite often involving different circumstances. Separated children are especially vulnerable as they may be accompanied by an adult who is abusive, a smuggler or a trafficker, or unable to effectively take care of them.

Separated children are entitled to protection under a broad range of international and regional instruments. These include the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), guided by CRC Committee General Comments No. 6 and 14, and the Hague Convention for the Protection of Children. According to Article 24 (2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (the Charter), the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration in all actions affecting children, including separated children in the asylum and migration context. All EU Directives relevant to unaccompanied children are also applicable to separated children, such as the Directive on Reception Conditions, the Dublin Regulation and the Asylum Procedures Directive.

This thematic focus concentrates on separated children, as well as on safeguards concerning family reunification and monitoring arrangements that are applicable to unaccompanied children in general.

Main findings

- Member States do not collect data on separated children, since they are – when registered – generally registered as unaccompanied children. Anecdotal evidence suggests that most separated children are boys between the ages of 13 and 17 years from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, and accompanied by a sibling, uncle, aunt or grandparents. They travel without their parents, who stay in the country of origin to protect their house or land, or because the family could only afford the traveling costs for one of its members.

- In all Member States’ legal frameworks, separated children are subsumed under unaccompanied children, except for some implementation differences concerning accommodation, the specific situation of married children, and guardianship/legal representation.

- There is a general lack of guidance and protocols regarding separated children; thus, responses vary by region, municipality, specific actor or even reception facility. Evidence suggests that child protection authorities are not always involved and play a weak role in most procedures related to separated children.

- Separated children are reportedly not informed in an appropriate and child-friendly way about asylum procedures, the possibility of applying independently for asylum and the consequences of different choices.

- Although officially considered unaccompanied children, separated children are often accommodated together with the accompanying adult until their relationship is assessed, without any protective measures in place. This entails serious risks for the child, given that the accompanying adult could be a smuggler, a trafficker or an abusive relative.

- Establishing the relationship and family ties between a child and the accompanying adult is difficult given the lack of official documentation. DNA testing is not often used due to its high cost. Few Member States have procedures to assess the quality of the relationship and the adult’s ability to care for the child. There are even cases where the accompanying adult is assigned as guardian/legal representative or carer of the child without a proper assessment of the child’s best interest.

- Responses to migrant children married abroad are not standardised. A majority of Member States recognise, under certain conditions, the marriage of a child that took place in a third country. Practices concerning the accommodation of children’s spouses differ. Referral to child protection authorities is not a general rule.

- Migration authorities mainly determine whether transferring a child for family reunification purposes is in the child’s best interests; child protection authorities and guardians sometimes also play a role.

- Different actors carry out the monitoring of reception facilities; there is often a lack of coordination and a lack of clarity as to who holds ultimate responsibility.