Access to adequate healthcare is essential for physical and mental health (see ‘Legal corner’). Untreated chronic conditions can increase the long-term healthcare costs for individuals and host countries.

Healthcare is primarily in the remit of Member State central authorities. Local authorities support access to services, and share in the responsibility for managing healthcare facilities to some extent. This section describes three measures that have facilitated access to healthcare at local level, illustrating them with examples.

Local authorities facilitated registration for healthcare in conjunction with registration for temporary protection.

In Austria, displaced people are entitled to benefits of the regular healthcare system as soon as they register for temporary protection [165] Austria, information provided by the Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023.

. Staff of the provincial police are present at the arrival centre in Vienna and generate national insurance numbers directly as part of the initial police registration [166] Austria, information provided by the Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023.

.

In Belgium, displaced people can register for free public health insurance upon applying for temporary protection.

In France, all displaced people from Ukraine with temporary protection status in France may benefit from universal health protection and complementary health insurance. That immediately covers health costs, besides family benefits and free childcare. The insurance coverage is issued automatically upon obtaining temporary protection status, and is valid for 12 months.

In Ireland, temporary protection beneficiaries are entitled to a medical card, which allows them to visit a doctor for free. They can also obtain medication and other medical services at a reduced price.

Local healthcare facilities benefited from facilitated integration of healthcare staff from Ukraine. That included eased requirements, upgrading courses and supervision programmes.

In Czechia, for example, the health system had relied on medical professionals from Ukraine for many years. A total of 693 doctors who had acquired their diplomas in Ukraine were already working in the country by 3 March 2022, just after the beginning of the war.

The arrival of displaced people, especially mothers with children, increased the demand for doctors providing primary care for children and adults, as well as speech therapists, psychologists and special educators. For this reason, Czechia eased qualification requirements for certain professions were eased in the fields of education, psychology and speech therapy. A special recognition process applies to temporary protection beneficiaries who are medical professionals with diplomas acquired outside the EU. Doctors must spend at least three months under the supervision of a doctor with a recognised diploma before they can start practising on their own.

In Estonia, the Ministry of Social Affairs created guidelines for integrating temporary protection beneficiaries into the Estonian healthcare system. To work as a healthcare worker in Estonia, healthcare professionals with education from third countries must be registered with the Health Board. It checks that their education complies with Estonian requirements.

Since temporary protection beneficiaries may not have original documents regarding their education or work experience, the Ministry of Social Affairs cooperates with Ukrainian institutions to accept documents from Ukrainian registers in electronic form. The person is then directed to take a compliance exam. It consists of work practice and a theory exam in Estonian.

Nurses and midwives can work in Estonia as caregivers or in other support functions, since their education in Ukraine is shorter than it would be in the European Union. In cooperation with healthcare universities, a study programme specially aimed at Ukrainian nurses is being developed.

In Poland, local authorities have helped healthcare professionals to find internships or voluntary service opportunities in local clinics and hospitals during the diploma recognition process [167] Poland, Healthcare Department of Lublin municipal authority, 5 January 2023.

.

Local authorities have provided specific information on healthcare rights, including through information campaigns, counselling and specific websites. Examples include Tallinn, Warsaw, Katowice and Lublin.

In Bruges, Belgium, guides in diversity, social services case workers and care point staff regularly inform temporary protection beneficiaries about the Belgian healthcare system [168] Belgium, guide in diversity, Bruges, 2 February 2023.

. The Brussels regional government created a special health orientation centre that provided personalised information on accessing the health system until its closure in December 2022.

In 2023, the organisation of a Social and Health Orientation Centre was entrusted to the Ukraine Voices Refugee Committee. That is a non-profit organisation that Ukrainian volunteers created under the umbrella of the United Nations Refugee Agency. The centre will be in a community centre, where activities organised by and for the community take place [169] Belgium, information provided by the national authorities when reviewing this report in July 2023.

.

In France, a leaflet available in French and Ukrainian informs temporary protection beneficiaries and medical insurance organisations about beneficiaries’ rights regarding covering the costs of consultations, treatments and medicine.

In Ireland, the Health Service Executive (HSE) has a thorough guide to the Irish health systemin English and Ukrainian for refugees and other migrants (see promising practice box). HealthConnect is a multilingual mobile-friendly website. It provides information on accessing health services for migrant communities in Ireland and is available in Ukrainian. Spunout has information specifically for children and young people on healthcare access across Ireland. The HSE website also provides information on how to access free, safe, and confidential sexual assault treatment units and about services for people with disabilities.

Local health authorities in Lublin and Warsaw, Poland, recognised the difficulty of providing information on healthcare [170] Poland, interview with the Healthcare Department of Lublin municipal authority, 5 January 2023; reply from Healthcare Department of Warsaw City Council, 21 February 2023.

. Warsaw therefore developed leaflets and posters on the functioning of the healthcare system, in Polish and Ukrainian, and opened a special hotline providing information on health services [171] Poland, Healthcare Department of Warsaw City Council, 21 February 2023.

. Medical care coordinators were appointed in all healthcare entities created by the city. Their job was to cooperate with the Social Welfare Coordinator in identifying and securing the health needs of displaced people and to organise adequate medical care on the premises of the medical facility [172] Poland, Healthcare Department of Warsaw City Council, 21 February 2023.

. Information campaigns focused on specific issues, for example the campaign on vaccinations for children carried out in cooperation with UNICEF.

In Slovakia, the Ministry of Health told healthcare providers how much healthcare to provide to temporary protection status holders and applicants, and anyone fleeing the war in Ukraine [173] Slovakia, information provided by the Ministry of Health, 31 January 2023.

. The General Health Insurance Company also prepared a manual on how to report each medical procedure for reimbursement. However, healthcare providers tended to refuse patients from Ukraine, as they did not have enough information about how they would be reimbursed [174] Slovakia, interview with a representative of the COMIN centre, Nitra, 14 July 2022.

.

Pre-existing bottlenecks in Member States’ healthcare systems made it difficult for local authorities to ensure healthcare for all arriving temporary protection beneficiaries.

Specific obstacles relate to additional administrative requirements for healthcare professionals, gaps in healthcare rights or insurance coverage, the need for psychological care, language barriers, and identifying and considering people with special needs.

In many locations, healthcare workers faced more administrative tasks when treating temporary protection beneficiaries than when treating other patients. In some, this resulted in delays/long waiting lists, overuse of emergency care, limited specialist attention or delayed medical procedures.

As solutions, local authorities contracted private practices (Tallinn)[175] Estonia, Tallinn City Government (Tallinna linnavalitsus), Interview with the head of the Department for Supporting the Integration of New Immigrants, 17 January 2023.

, provided lists of doctors who accept new patients (Bruges) [176] Belgium, interview with the coordinator of the PCSW, Bruges, 23 January 2023.

, identified family doctors for refugee-inclusive clinics (Bucharest), operated low-threshold drop-in clinics (Bratislava) and facilitated the integration of healthcare professionals from Ukraine (Czechia, Estonia, Poland,[177] Poland, Healthcare department of Lublin, 5 January 2023; Healthcare department of Warsaw, 21 February 2023.

Slovakia).

Czechia, for example, lacks family doctors and specialised doctors. Two in five temporary protection beneficiaries considered the capacities of the healthcare system to be insufficient, according to a survey conducted in September 2022. Some explicitly stated that doctors did not accept them as patients.

In Tallinn, Estonia, family doctors may refuse to accept new patients, which has affected temporary protection beneficiaries. A contract with the private practice Confido has proven helpful. It allows displaced people to immediately receive high-quality service and, if necessary, referral to other specialists [178] Estonia, interview with the head of the Department for Supporting the Integration of New Immigrants, Tallinn City Government, 17 January 2023.

.

The town of Portmagee in Kerry, Ireland, has only four GPs in the area and is far away from acute hospital services. Local councillors have expressed concern that meeting the needs of those living there is proving to be a challenge. Rural access to family doctors became even more difficult for temporary protection beneficiaries because they were accommodated in large groups and transport was challenging [179] Ireland, interview with representatives from Kerry HSE, 1 March 2023.

. A major challenge arose when temporary protection beneficiaries applied for medical cards and the authorities subsequently moved them to other accommodation without organising a forwarding service [180] Ireland, interview with a representative from Cairde, 12 January 2023.

.

A general lack of family doctors makes it challenging in certain parts of the country for temporary protection beneficiaries to get a named family doctor on their medical cards. To address this issue, sessional family doctor clinics are being arranged at accommodation centres [181] Ireland, information provided by the national authorities when reviewing this report in July 2023.

.

In Bucharest and Constanța, Romania, temporary protection beneficiaries had only a minor impact on the medical system despite unlimited access under the same conditions as for Romanian citizens. However, technical difficulties in registering with a family doctor were a common barrier.

Only the few family doctors that the authorities listed for each county accepted patients from Ukraine, for bureaucratic reasons. A consultation takes longer than with Romanian patients because of administrative requirements. Doctors receive less financial compensation. In some cases, doctors refused patients from Ukraine, as their temporary protection ID cards did not show a registered address because they moved frequently or were in collective accommodation.

For this reason, temporary protection beneficiaries in Bucharest resorted to emergency services even for non-emergency conditions.

In Bratislava, Slovakia, doctors often refuse temporary protection beneficiaries because they are unable to accept new patients or fear that the General Health Insurance Company will not reimburse the medical procedure. Specialists can only report medical procedures under three codes that the Ministry of Health has specifically designated for healthcare provided to temporary protection beneficiaries. The lump sums corresponding to these codes do not fully cover the real costs of the medical procedures [182] Slovakia, interview with the head of the outpatient clinic for temporary protection holders from Ukraine, Bratislava, 23 January 2023.

.

Furthermore, the General Health Insurance Company does not always reimburse the costs of medical procedures provided to temporary protection beneficiaries. In such cases it tends to inquire specifically if the procedure was necessary and why, before paying [183] Slovakia, interview with the outpatient clinic for temporary protection holders from Ukraine, 1 March 2023.

. This requires additional administrative effort.

In Bratislava and Nitra, support organisations such as Tenenet help temporary protection beneficiaries trying to set up appointments with specialist doctors [184] Slovakia, interview with a representative of Tenenet, Bratislava, 27 January 2023.

. However, this is a time-consuming additional task. It may take some 30 phone calls to get through to the specialist needed [185] Slovakia, interview with the head of the outpatient clinic for temporary protection holders from Ukraine, Bratislava, 23 January 2023.

. For this reason, the outpatient clinic for temporary protection holders from Ukraine has also treated patients with chronic diseases unless specialist attention was absolutely necessary.

In most Member States, people gain more healthcare rights when they registration or receive temporary protection permits. That entitles them to statutory healthcare provided within the public health insurance system as well as emergency care.

An exception is Slovakia, where temporary protection beneficiaries may only get medically indicated necessary care. They have full benefits as available to nationals only if they are employed for more than the minimum wage (€ 646 a month).

In Sweden, beneficiaries can still have only the same care asylum applicants. That includes emergency medical care, emergency dental care and medical care ‘that cannot wait’ subject to the health service’s assessment.

Gaps may also arise if healthcare access depends on permits that are not yet issued. For example, in Belgium, it is difficult to register for health insurance without a residence permit and to have disabilities recognised [186] Belgium, interview with the team of the Helpdesk Ukraine at Caritas International, Brussels, 2 February 2023.

. In exceptional cases, social services can provide access to urgent medical help before a person is registered for temporary protection, according to instructions from the Federal Department for Social Integration.

In Germany, one needs a residence permit or a fiction certificate to be entitled to general healthcare benefits. Until then, beneficiaries have the same access to healthcare as asylum applicants.

In Ireland, temporary protection beneficiaries are entitled to the same medical care and social welfare benefits as Irish citizens. To access services, some of which are free of charge, they must apply for a medical card.

In Italy, temporary protection beneficiaries similarly need to get a health card after registering with the local health authorities and getting a fiscal code. The card allows them free prescriptions and visits by GPs and/or paediatricians. Lazio region provided a guide listing the bodies authorised to issue the card.

In Poland, access to healthcare generally requires a PESEL. Temporary protection beneficiaries may apply for one within 30 days. However, one may also prove one’s right to healthcare benefits by submitting a declaration instead of a PESEL. The Ministry of Health developed a template for such a declaration in Polish, Ukrainian and Russian.

Many people have trauma resulting from war-related experiences. That makes access to mental healthcare crucial. In most Member States, temporary protection beneficiaries may access psychological and psychiatric care as provided in the national healthcare system. They usually require a referral by a GP.

In practice, psychological care is primarily provided by NGOs, for example in Bratislava, Nitra, Styria and Vienna. Services are more easily and quickly accessible than those through the public healthcare system. They are free of charge, with a low threshold and/or with interpreters or Ukrainian- or Russian-speaking professionals. Common challenges include long waiting lists, the lack of sufficient specialists and interpretation arrangements.

In Vienna, Austria, access to psychological care is provided in cooperation with NGOs. Sometimes there are long waiting times and fees [187] Austria, interview with the Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023.

.

In Belgium, public health insurance only partly covers psychological care. In Bruges, free of charge offers, for example provided by a psychologist from social services or NGOs such as Solentra, may entail long waiting times [188] Belgium, interview with the coordinator of the PCSW, Bruges, 23 January 2023.

.

In Saaremaa, Estonia, children receive support from school psychologists. Adults face long waiting times, as the number of psychologists is limited, although Ukrainian psychologists have been employed for help [189] Estonia, response to information request, Saaremaa Municipality Government, 12 January 2023.

. The Tallinn refugee centre employs two Ukrainian psychologists offering free consultations and would benefit from a third psychologist [190] Italy, interview with the head of the Department for Supporting the Integration of New Immigrants, Tallinn City Government, 17 January 2023.

.

In Naples, Italy, NGOs help temporary protection beneficiaries to access psychological services. Many of them report post-traumatic stress disorder [191] Italy, interview with two representatives of Cidis Onlus, Naples, 9 March 2023.

. The NGO ActionAid noted language and cultural barriers. They sometimes result in a lack of cooperation from the authorities [192] Italy, interview with the Global Inequality and Migration Unit of ActionAid, Naples, 12 January 2023.

.

In Bratislava, Slovakia, it is mainly NGOs such as Tenenet that provide psychological help at local level [193] Slovakia, interview with a representative of the COMIN centre, Nitra, 14 July 2022.

. Psychiatric outpatient clinics were overburdened in mid-2022 [194] Slovakia, interview with a representative of Tenenet, 14 July 2022.

.

Local authorities in many Member States considered the language barrier the main challenge in providing healthcare.

Health insurance usually does not cover the costs of interpreters necessary for medical treatment (see consultation findings box). However, reimbursement may be possible upon application in special individual cases where necessary (Germany, Estonia) [195] Estonia, interview with the head of the Department for Supporting the Integration of New Immigrants, Tallinn City Government, 17 January 2023.

. An exception is Ireland. The HSE has a duty under legislation to ensure that information and services are accessible to all (see promising practice box). In practice, that requires hospitals to request the services of an interpreter if needed, at no cost to the patient [196] Ireland, consultation with a representative from Cairde, 12 January 2023.

.

Local-level solutions have included video interpretation (Vienna) [197] Austria, Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023.

, relying on volunteers from the Ukrainian community (Stuttgart) and employing Ukrainian- or Russian-speaking healthcare staff (Saaremaa, Lublin, Warsaw) [198] Estonia, response to information request, Saaremaa Municipality Government, 12 January 2023; Poland, interview with the Healthcare Department of Lublin municipal authority, 5 January 2023; Health Department of Warsaw City Council, 21 February 2023.

. Local authorities consulted considered it useful to establish short-term agreements with interpreters and a structured procedure for involving them temporarily in case of future need.

In Brussels, Belgium, various services partly resolved language barriers. Examples were the NGOs Caritas, SeSo and Convivial; the mobile team organised by Ukrainian Voices Refugee Committee [199] Belgium, interview with the team of the Helpdesk Ukraine, Caritas International, Brussels, 2 February 2023.

; and Brussels Onthaal and SeTIS [200] Belgium, information provided by the national authorities when reviewing this report, July 2023.

. In Bruges, health professionals and social service case workers can use the interpretation service of social services. It has approximately 15 interpreters for Ukrainian and Russian.

In Tallinn, Estonia, local authorities may reimburse translation costs during the first two years after protection is granted. They receive funding for this based on contracts with the Social Insurance Board. It will pay translation costs for administrative situations in local governments, state institutions, educational institutions and “other places that require translation”. However, the procedure for applying for the compensation is unclear.

Saaremaa municipality used this option often: some 200 times by the end of December 2022. Its Kuressaare hospital employed one Ukrainian- and Russian-speaking temporary protection beneficiary as an interpreter while also using online translation services such as Google Translate [201] Estonia, response to information request, Saaremaa Municipality Government, 12 January 2023.

.

In France, temporary protection beneficiaries were uncomfortable relying on Russian-speaking interpreters, NGOs pointed out [202] France, interview with a representative of Mon coeur ukrainien, Île-de-France, 17 January 2023.

.

Local authorities in Germany set up agreements with hospital associations to offer scheduled time slots with interpreters. In Stuttgart, the relevant city department quickly set up a pool of interpreters with the help of the local Ukrainian community [203] Germany, consultation with the Department of Social Affairs and Integration, Stuttgart, January 2023.

. In Berlin, the programme SprInt offers language mediation in the health sector. It has increased and supplemented its services by adding Ukrainian and Russian language mediation [204] Germany, consultation with the Berlin Senate Department for Integration, Labour and Social Affairs, January 2023.

.

The city of Lublin, Poland, cooperated with the Voluntary Service Centre. This organisation offers various forms of support to migrants, including assistance with visits to doctors. However, there is no legal requirement to provide interpretation during visits to doctors or hospitals.

In Romania, doctors often used online translation tools. In Constanța, an integrated community centre was set up that also hosts interpreters.

The TPD requires Member States to provide medical or other assistance to people who have special needs (see consultation findings box), such as unaccompanied children or people who have undergone torture, rape or other serious forms of violence. The high prevalence of vulnerability among arrivals made it difficult for local authorities to provide adequate support. In addition, many displaced people had further or multiple vulnerabilities besides the examples listed in the TPD. This required flexibility and a broad interpretation of assistance required for people, for example, single parents with children, traumatised people, possible victims of trafficking or people susceptible to labour exploitation.

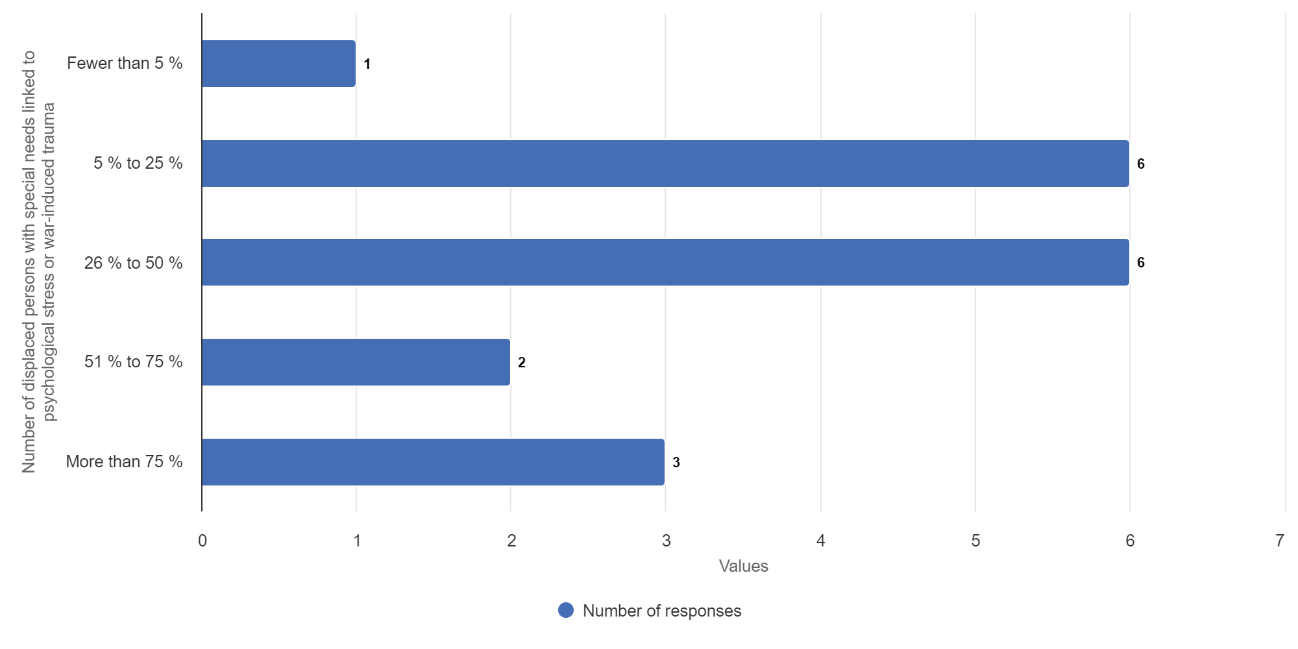

Figure 4 – Displaced people with special needs linked to psychological stress or war-induced trauma

Alternative text: A bar chart showing how many organisations gave each answer. One organisation responded ‘fewer than 5 %’, six responded ‘5 % to 25 %’, six responded ’26 % to 50 %’, two responded ’51 % to 75 %’ and three responded ‘more than 75 %’.

Question: “Based on your experience supporting displaced persons, how many have special needs linked to psychological stress or war-induced trauma?” 12 respondents indicating ‘don’t know’ are not reflected in the numbers.

Source: online consultation with 30 support organisations in 17 locations

Local authorities provided support to people with special needs, primarily those with disabilities and people who had experienced violence or torture.

Styria, Austria, saw an especially high number of victims of torture in late summer and autumn 2022, including from occupied territories in Ukraine [205] Austria, interview with a member of the Integration Centre Styria, 24 January 2023. . Victims were frequently identified during German language courses and in seminars dealing with issues of victim support in Austria. Almost all displaced Ukrainians attend these language courses, so they are very likely to access information and contact details about these services. Thus, organisations that provide language courses are good sources of information about this [206] Austria, interview with a member of the Integration Centre Styria, 24 January 2023. . The Integration Centre Styria refers clients to an NGO called Zebra, which offers psychological support and trauma therapy, or to the women’s shelter. In Vienna, referrals are made to the association Hemayat – Care Centre for Torture and War Survivors [207] Austria, Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023. .

In Poland, when people are suspected of having suffered psychological, physical and sexual violence, the procedure includes several stages. Initial verification is through an interview and examination. Detailed information about the available support is provided. Then come medical examination and treatment. Information is forwarded to the police, unless the violence was in Ukraine, and/or the local centre for family assistance.

Community healthcare organisations (CHOs) in Dublin and Kerry, Ireland, have created mobile, or in-reach, teams. They go into accommodation settings to conduct health assessments, through which they hope to catch any particular special needs. Setting up health assessments immediately upon arrival proved not conducive to disclosure of violence or mental health needs.

Dublin’s CHO9 has made referrals to the National Centre for Survivors of Torture in Ireland for specific mental health support when it has identified victims of torture [208] Ireland, consultation with a representative from Cairde, 12 January 2023. . South Dublin County Council’s website also provides information on services for those experiencing violence.

When CHO4 in Kerry goes into group accommodation settings and meets unaccompanied children, the members look for documentary evidence that a family member is present with them. If not, they refer the child to Tusla [209] Ireland, consultation with representatives from Kerry HSE, 1 March 2023. .

There is huge stigma around mental health in the Ukrainian population. Members are reluctant to contact the police, and do not trust state institutions to report abuse taking place in accommodation [210] Ireland, consultation with a representative from Cairde, 12 January 2023. . Differences in disability schemes are an obstacle to accessing adequate care [211] Ireland, information gained from a Ukraine Civil Society Forum, 6 December 2022. .

Concerning assistance to people with disabilities, the Integration Centre in Styria reported challenges in dealing with deaf-mute temporary protection beneficiaries, since communication had to be paid for privately or through donations [212] Austria, interview with the Integration Centre Styria, 24 January 2023. . In Vienna, qualified case managers assess the needs of temporary protection beneficiaries with disabilities [213] Austria, information provided by the Vienna Social Fund, 24 January 2023. . Benefits from the disability assistance or care system are also granted, subject to the same prerequisites as for anybody else.

Tableexample, they book appointments and refer them to specialised services such as Huis van het Kind (‘House of the Child’) or the FOD Personen met een handicap (Federal Agency for People with a Disability). In Brussels, the administrative recognition of disabilities can present barriers. Some people had difficulties understanding what their health insurance covered and the additional costs involved [214] Belgium, interview with the team of the Helpdesk Ukraine, Caritas International, Brussels, 2 February 2023. .

In Bucharest and Constanța, Romania, local authorities had limited resources to ensure access to rehabilitation centres for children or adults with disabilities. The centres offered services such as speech therapy, behavioural therapy for children diagnosed with autism, and physiotherapy for people recovering from injuries or other chronic illnesses. Several NGOs provided some of these services in both Bucharest and Constanța [215] Romania, interview with the head of the General Directorate for Social Assistance and Child Protection, Bucharest, 7 February 2023. .

In Slovakia, victims of sexual violence from Ukraine do not systematically receive assistance. The COMIN centre had several victims of sexual violence in its care, and cooperated with the Slniečko Centre, helping abused and sexually abused children and victims of violence [216] Slovakia, interview with a representative of the COMIN centre, Nitra, January 2023. .

The Tenenet Association assesses the kinds of disability and related restrictions of children from Ukraine so that they can receive financial benefits. It cooperates with UNHCR, UNICEF and the NGO Platform of Families of Children with Disabilities. The municipality in Nitra opened a grant programme that would make it possible to apply for reimbursement for medical devices and medicines for children from Ukraine under two years of age.