The chapter also sets out some of the key legal drivers of ensuring that older persons have equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation, although the timeline for the process of digitalisation varies between Member States.

The chapter is divided in two sections. The first section analyses the legal framework addressing equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. The second addresses national policy frameworks – digital strategies, action plans or comparable policies related to digitalisation for addressing equal access for everyone to public services that are undergoing digitalisation – and then focuses particularly on older persons.

All EU Member States guarantee the general principle of non-discrimination in their constitutions or basic laws. While all EU Member States have legal frameworks in place regulating the digitalising of public services, the national legal frameworks address to varying degrees and in different ways the issue of equal access and the principle of non-discrimination in the context of digitalisation.

Two main approaches were identified. Member States either guarantee equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation in ‘e-government laws’, which generally regulate the digitalisation of public administration, or have adopted specific/sectoral legislation (in laws regulating access to health, to social security, to information, etc.).

There are therefore two basic ways that Member States address equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. Some guarantee it for everyone as a general principle, which should be applied horizontally and complements the principles of good administration as also guaranteed in Article 41 of the Charter. Others explicitly guarantee the right of equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation (for instance the right to equal access to public services). Both ways are then addressed either in the generic e-government law or in the sectoral laws in the country in question (see Table 1).

The first approach, guaranteeing the right to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation in generic e-government laws, is found in 13 countries (12 EU Member States and Serbia). 11 EU Member States have approach 1 only.

The second approach, guaranteeing the right to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation in particular/sectoral laws, is found in 18 countries (17 EU Member States and North Macedonia). 16 EU Member States have approach 2 only.

Only two EU Member States, France and Latvia, have more developed frameworks, which guarantee the right to equal access to digitalising services both in e-government laws and in specific laws.

Table 1 – National laws regulating equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation, by approach and country

|

Country

|

Approach 1: E-government law guarantees equal access to digital public services |

Approach 2: Particular laws guarantee equal access to particular digital public services |

||

|

Explicit access guaranteed (Approach 1.a) |

Access guaranteed as a general principle (Approach 1.b) |

Explicit access guaranteed (Approach 2.a) |

Access guaranteed as a general principle (Approach 2.b) |

|

|

Austria |

|

|

x |

|

|

Belgium |

|

|

x |

|

|

Bulgaria |

x |

|

|

|

|

Croatia |

|

|

x |

|

|

Cyprus |

|

|

x |

|

|

Czechia |

x |

|

|

|

|

Denmark |

|

|

x |

|

|

Estonia |

x |

|

|

|

|

Finland |

x |

|

|

|

|

France |

|

x |

|

x |

|

Germany |

x |

|

|

|

|

Greece |

|

x |

|

|

|

Hungary |

|

|

x |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

x |

|

|

Italy |

|

x |

|

|

|

Latvia |

|

x |

x |

|

|

Lithuania |

|

|

x |

|

|

Luxembourg |

|

x |

|

|

|

Malta |

|

|

|

x |

|

Netherlands |

|

|

x |

|

|

Poland |

|

|

|

x |

|

Portugal |

|

|

|

x |

|

Romania |

|

|

x |

|

|

Slovakia |

|

|

x |

|

|

Slovenia |

|

|

x |

|

|

Spain |

|

x |

|

|

|

Sweden |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

North Macedonia |

|

|

x |

|

|

Serbia |

x |

|

|

|

|

Total per category |

7 |

6 |

14 |

4 |

Sources: FRA, 2022 (data collection refers to valid and effective legislation in EU Member States, North Macedonia and Serbia as of 31 May 2022).

In 12 Member States and Serbia, the national general e-government law guarantees, in some degree, equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation, either explicitly or as a principle, FRA findings indicate. Seven countries explicitly guarantee equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation (Bulgaria, [100] Bulgaria, Electronic Government Act (Закон за електронното управление), 12 June 2007, last amended 22 February 2022.

Czechia, [101] Czechia, Act No. 12/2020 Coll. on the right to digital services (Zákon č. 12/2020 Sb. o právu na digitální služby), 17 January 2020.

Estonia, [102] Estonia, Public Information Act (Avaliku teabe seadus), 15 November 2000, § 32 (1) 6.

Germany, [103] Germany, Act to improve online access to administrative services (Gesetz zur Verbesserung des Onlinezugangs zu Verwaltungsleistungen (Onlinezugangsgesetz – OZG)), 14 August 2017.

Finland, [104] Finland, Administrative Procedures Act (hallintolaki/förvaltningslag), Act No. 434/2003, 6 June 2003.

Serbia [105] Serbia, Electronic Government Act (Zakonoelektronskojupravi), 6 April 2018.

and Sweden [106] Sweden, Administrative Procedure Act (2017:900) (Förvaltningslag (2017:900)), 28 September 2017; Sweden, Instrument of Government (Kungörelse (1974:152) om beslutad ny regeringsform), 28 February 1974.

). National regulations in these seven countries contain similar provisions on electronic governance, laying down freedom of choice as a general principle in ensuring that all users have free and equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation without any discrimination (see Table 1, Approach 1.a).

Member States’ e-government laws address grounds for discrimination to varying degrees. Some refer to only some grounds, but in Sweden, for example, the Instrument of Government contains provisions to ensure the “equality of all before the law” [107] Sweden, Instrument of Government (Kungörelse (1974:152) om beslutad ny regeringsform), 28 February 1974, Chapter 1, Section 9.

and to “combat discrimination of persons on grounds of gender, colour, national or ethnic origin, linguistic or religious affiliation, functional disability, sexual orientation, age or other circumstance affecting the individual”, naming age explicitly. [108]Ibid., Chapter 1, Section 2.

In Serbia, the Electronic Government Act addresses the right to equal access explicitly by stipulating that “everyone has the right to use the e-government service”. [109] Serbia, Electronic Government Act (Zakon o elektronskoj upravi), 6 April 2018.

In Czechia, the Act on the right to digital services ensures the right of “natural and legal persons to the provision of digital services by public authorities in the exercise of their competences” and “the obligation of public authorities to provide digital services.” [110] Czechia, Act No. 12/2020 Coll. on the right to digital services (Zákon č. 12/2020 Sb. o právu na digitální služby), 17 January 2020.

In the explanatory memorandum, the authors of the act emphasise that “anchoring the right to provide a digital service in no way excludes or limits the use of existing methods of service provision by public authorities at the choice of the service user”.

On the other hand, some Member States grant equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation in the form of a more general principle of non-discrimination and access to what is called digital governance (see Table 1, Approach 1.b). This group is composed of six Member States: France, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg and Spain.

For example, France has adopted a Law for a Digital Republic [111] France, Law No. 2016-1321 for a digital republic (Loi n° 2016-1321 pour une République numérique), 7 October 2016.

to ensure digital access for all. The Spanish eGovernment Act [112] Spain, Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with Parliament and Democratic Memory (Ministerio de la Presidencia, las Relaciones con las Cortes y la Memoria Histórica), Royal Decree 203/2021 of 30 March 2021 approving the regulation on the performance and functioning of the public sector by electronic means (Real Decreto 203/2021, de 30 de marzo, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de actuación y funcionamiento del sector público por medios electrónicos), 30 March 2021.

sets out an accessibility principle, defined as “the set of principles and techniques to be respected in the design, construction, maintenance and updating of electronic services to ensure equality and non-discrimination in access for users”.

A number of countries use particular/sectoral laws to address equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. For instance, they may be related to e-health, electronic signature, access to information or social security services. Again, as with the previous grouping, provisions are either explicit (see Table 1, Approach 2.a) or as a general principle (see Table 1, Approach 2.b).

For example, Slovakia has two main laws covering the digitalisation of public administration: the Act on Information Technologies in Public Administration [113] Slovakia, Act 95/2019 Coll. on information technologies in public administration and on amendments to certain acts (Zákon č. 95/2019 Z.z. o informačných technológiách vo verejnej správe a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov ), 18 April 2019.

and the Act on eGovernment. [114] Slovakia, Act 305/2013 Coll.Act on the Electronic Form of the Exercise of the Powers of Public Authorities and on Amendments to Certain Acts (e-Government Act) (Zákon č. 305/2013 Z.z. o elektronickej podobe výkonu pôsobnosti orgánov verejnej moci – Zákon o eGovernmente), 8 October 2013.

Neither of these laws contains a section guaranteeing equal access to digital public services. However, they both provide a framework for public services to be digitally accessible in areas such as health records, public statutory pensions and social benefits.

Austria’s eGovernment Act [115] Austria, eGovernment Act (E-Government-Gesetz), Federal Law Gazette (Bundesgesetzblatt) No. 10/2004, 27 February 2004.

lays down that users are free to choose how to contact public authorities, as a measure to ensure that people’s rights are respected. It does not explicitly recognise equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation as a guiding principle or set out a principle related to digital public administration. In Lithuania, the law on public administration [116] Lithuania, Law on public administration (Lietuvos Respublikos viešojo administravimo įstatymas), 17 June 1999, as amended November 2022.

refers to the principles of public administration, which should apply to all digital services. In the Netherlands, the Digital Government Act [117] Netherlands, State Secretary for the Interior and Kingdom Relations (2018), Bill for the Digital Government Act (Algemene regels inzake het elektronisch verkeer in het publieke domein en inzake de generieke digitale infrastructuur (Wet digitale overheid): Voorstel van wet), parliamentary document 34,972, No. 2, The Hague, House of Representatives.

ensures that Dutch citizens and businesses have access to government-related entities by digitalised means.

Specific laws address e-health services, including patients’ rights, in Belgium, Cyprus and Denmark. In Belgium, the Patients’ Rights Law [118] Belgium, Patients’ Rights Law (Loi relative aux droits du patient), 22 August 2002.

and the Law relating to the institution and organisation of the eHealth platform [119] Belgium, Law relating to the institution and organisation of the eHealth platform (Loi relative à l’institution et à l’organisation de la place-forme eHealth), 21 August 2008.

recognise the rights of patients to information. Similarly, in Cyprus, particular laws grant equal access to e-health, information, electronic signatures and electronic judicial services. [120] Cyprus, The eHealth Law of 2019 (O περί Ηλεκτρονικής Υγείας Νόμος του 2019), 19 April 2019.

Denmark grants digital access to the e-health system, eID and the citizen’s portal, including digital post services. [121] For information on the official health portal, sundhed.dk, see Denmark (n.d.), ‘History of sundhed.dk’ (‘Historien om sundhed.dk’); Denmark, Ministry of Finance, Act No. 801 of 13 June 2016 on public digital post from public senders (LBK nr 801 af 13/06/2016 om digital post fra offentlige afsendere), 13 June 2016.

Legislation in Belgium, [122] Belgium, Law on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies (Loi relative à l’accessibilité des sites internet et des applications mobiles des organismes du secteur public), 19 July 2018.

Bulgaria, Croatia, [123] Croatia, Act on the right to access information (Zakon o pravu na pristup informacijama), Official Gazette (Narodne novine) No. 25/2013, 28 February 2013.

Hungary and Latvia explicitly addresses access to digital public services via a single electronic portal. According to the Bulgarian Electronic Government Act, for example, electronic administrative services are to be accessed through a single electronic portal and must be provided in an accessible manner, including for persons with disabilities.

Croatia takes the same approach of a central electronic portal. [124] Croatia, Law on the state information infrastructure (Zakon o državnoj informacijskoj infrastrukturi), Official Gazette (Narodne novine) No. 92/2014, 28 July 2014.

The legal framework establishes a central government portal system as a single point of contact in the virtual world. In contrast, Hungary [125]Hungary, Act CCXXII of 2015 on the general rules on electronic administration and trust services (2015. évi CCXXII. törvény az elektronikus ügyintézés és a bizalmi szolgáltatások általános szabályairól), 15 December 2015.

granted access to public services by digital means only, so certain public services are accessible only online or through a legal representative who has electronic access.

Latvia’s regulation for the Public Administration Services Portal [126] Latvia, Cabinet of Ministers, Rules of the public administration services portal (Valsts pārvaldes pakalpojumu portāla noteikumi), Regulation No. 400, 4 July 2017.

provides for equal treatment and non-discrimination. It also has concrete laws to grant access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation, such as social protection, social security, healthcare and customer rights. The Law on social security, for example, sets out that social services are provided without discrimination on the basis of a person’s race, colour, gender, age, disability, health condition, religious, political or other conviction, national or social origin, property or family status or other circumstances. [127] Latvia, Cabinet of Ministers, Regulations regarding the types of the unified customer service centres of the state administration, the scope of services provided and the procedures for the provision of services (Noteikumi par valsts pārvaldes vienoto klientu apkalpošanas centru veidiem, sniegto pakalpojumu apjomu un pakalpojumu sniegšanas kārtību), Regulation No. 401, 4 July 2017.

North Macedonia, Romania and Slovenia grant equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation in particular areas by addressing it in specific laws in combination with non-discrimination legislation. For example, North Macedonia established a legal framework for digital governance by adopting three interconnected laws: the Law on electronic documents, electronic identification and trusted services, [128]North Macedonia, Law on electronic documents, electronic identification and trusted services (Закон за електронски документи, електронска идентификација и доверливи услуги), Official Gazette of the Republic of North Macedonia (Службен весник на Република Северна Македонија) No. 98/2019, 21 May 2019.

the Law on electronic management and electronic services [129]North Macedonia, Law on electronic management and electronic services (Закон за електронско управување и електронски услуги), Official Gazette of the Republic of North Macedonia (Службен весник на Република Северна Македонија) No. 101/2019, 22 May 2019.

and the Law on the central population register. [130]North Macedonia, Law on the central population register (Закон за централен регистар на население), Official Gazette of the Republic of North Macedonia (Службен весник на Република Северна Македонија), No. 98/2019, 21 May 2019.

In Romania, three separate regulations address digitalising public services, however, none of them provides any specific measures or provisions to ensure equal access.

The Slovenian legislation is divided into three laws. They guarantee access to measures promoting digital inclusion for all targeted groups under equal conditions. The purpose of the laws is to increase digital inclusion among the population of Slovenia. Digital inclusion is defined as the ability of individuals to access the available information and communication infrastructure and digital technologies, solutions and services, use them competently and securely, trust them and thus actively participate in the information society.

The Protection against Discrimination Act [131]Slovenia, Protection against Discrimination Act (Zakon o varstvu pred diskriminacijo), 21 April 2016, and subsequent modifications.

is a cross-cutting act providing for protection against discrimination. The Promotion of Digital Inclusion Act [132]Slovenia, Promotion of Digital Inclusion Act (Zakon o spodbujanju digitalne vključenosti), 28 February 2022.

guarantees access to measures promoting digital inclusion for all targeted groups under equal conditions. The Accessibility of Websites and Mobile Applications Act [133]Slovenia, Accessibility of Websites and Mobile Applications Act (Zakon o dostopnosti spletišč in mobilnih aplikacij), 17 April 2018, and subsequent modifications.

regulates the measures and standards ensuring the accessibility of websites and mobile applications for all users.

Sixteen EU Member States have only particular laws and no generic regulations about equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. Two countries have both (France and Latvia). Four countries (France, Malta, Poland, Portugal) do not explicitly grant equal access, despite having concrete public services regulations. They refer instead to the principle of public administration and indirectly promote equal access by establishing mechanisms that enable access to digital public services for the general population. In Poland, for example, the Act on electronic delivery stipulates the right to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. [134] Poland, Act on electronic delivery (Ustawa o doręczeniach elektronicznych), 18 October 2020.

Although in Portugal the legislation available does not directly address the right to equal access, it may indirectly promote it by establishing mechanisms that enable access to digital public services for the general population. For instance, Decree-Law 74/2014 [135] Portugal, Decree-Law 74/2014, which establishes the rule of digital provision of public services, enshrines assisted digital attendance as its indispensable complement and defines the mode of concentration of public services in Citizens’ Bureaux (Decreto-Lei 74/2014, que estabelece a regra da prestação digital de serviços públicos, consagra o atendimento digital assistido como seu complemento indispensável e define o modo de concentração de serviços públicos em Lojas do Cidadão), 13 May 2014.

establishes the rule of digital provision of public services, according to which public services must be provided digitally as well as face to face. Furthermore, those who cannot, will not, or do not know how to use digital tools can receive support and direction from a public officer/digital mediator in ‘citizens’ shops’ (Lojas do Cidadão). The decree-law also sets out that the public officer/digital mediator plays a pedagogical role in promoting digital literacy regarding the use of digitalised public services.

The legal safeguard in all Member States is that there is at least a particular law focusing on a specific topic, incorporating the right to equal access to digitalised public services, even though in 16 Member States there is no general law granting equal access to digitalised public services.

In addition to the rights and principles related generally to the equal access to digital public services contained in e-government laws and/or particular/sectoral laws, certain national legal instruments also contain specific provisions recognising the risk of digital exclusion for particular population groups. [136]Fang, M. L., Canham, S. L., Battersby, L., Sixsmith, J., Wada, M. and Sixsmith, A. (2019), ‘Exploring privilege in the digital divide: Implications for theory, policy, and practice’, The Gerontologist, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. e1–e15.

The laws of four EU Member States related to public services that are undergoing digitalisation make specific provision for older persons as a group that is potentially vulnerable to digital exclusion and therefore at risk of being disenfranchised from equal access to digital public services. Those countries are Denmark, Greece, Slovenia and Spain. The remainder do not specifically regulate older persons’ equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation.

The Danish parliament adopted an extensive legal framework on mandatory digital self-service in 2012–2015. [137] Denmark, Ministry of Finance (Finansministeriet), Act. No. 558 of 18 June 2012 amending the Act on the Central Person Register, the Act on day, leisure, and club offers to children and adolescents, the Public Schools Act and the Health Act (Lov nr. 558 af 18. juni 2012 om ændring af lov om Det Centrale Personregister, lov om dag-, fritids- og klubtilbud m.v. til børn og unge, lov om folkeskolen og sundhedsloven), 18 June 2012; Denmark, Ministry of Finance (Finansministeriet), Act No. 622 of 12 June 2013 amending various legal provisions on applications, notifications, requests, notices and declarations to public authorities (Lov nr. 622 af 12. juni 2013 om ændring af forskellige lovbestemmelser om ansøgninger, anmeldelser, anmodninger, meddelelser og erklæringer til offentlige myndigheder), 12 June 2013; Denmark, Ministry of Finance (Finansministeriet), Act No. 552 of 2 June 2014 on amending various legal provisions on applications, notifications, notices, requests and declarations to public authorities (Lov nr. 552 af 2. juni 2014 om ændring af forskellige lovbestemmelser om ansøgninger, anmeldelser, meddelelser, anmodninger og erklæringer til offentlige myndigheder), 2 June 2014; Denmark, Ministry of Finance (Finansministeriet), Act No. 742 of 1 June 2015 amending various legal provisions on applications, requests, notices and complaints to public authorities (Lov nr. 742 af 1. juni 2015 om ændring af forskellige lovbestemmelser om ansøgninger, anmodninger, meddelser og klager til offentlige myndigheder), 1 June 2015.

Digital self-service means that public services are available without the help of human beings, and individuals gain access to digital services entirely online. The framework emphasises that consideration must be shown to citizens who are unable to acquire digital competencies, and to citizens with special needs such as older citizens, citizens with disabilities or dementia, socially vulnerable citizens, foreign citizens in Denmark and Danes residing abroad. [138] Danish Agency for Digital Government (Digitaliseringsstyrelsen), ‘Legislation on mandatory digital self-service’ (‘Lovgivning om obligatorisk digital selvbetjening’).

In Greece, the Digital Governance Law [139] Greece, Law No. 4727/2020: Digital governance (integration in Greek legislation of Directive (EU) 2016/2102 and Directive (EU) 2019/1024) – Electronic communications (integration in Greek law of Directive (EU) 2018/1972) and other provisions (Nomoσ Υπ’ Αριθμ. 4727: Ψηφιακή Διακυβέρνηση (Ενσωμάτωση στην Ελληνική Νομοθεσία της Οδηγίας (ΕΕ) 2016/2102 και της Οδηγίας (ΕΕ) 2019/1024) – Ηλεκτρονικές Επικοινωνίες (Ενσωμάτωση στο Ελληνικό Δίκαιο της Οδηγίας (ΕΕ) 2018/1972) και άλλες διατάξεις), Government Gazette (Φύλλα Εφημερίδας της Κυβέρνησης) A’184/2020, 23 September 2020, Art. 111.

refers specifically to older persons in the section regarding the general objectives. It stipulates that “The state must promote the interests of the citizens by ensuring connectivity and the widespread availability and take-up of very high capacity networks, [...] by ensuring a high and common level of protection […] and by addressing the needs, […], of specific social groups, in particular end-users with disabilities, older persons end-users and end-users with special social needs”.

Spain ensures equality and non-discrimination in access for users, in particular persons with disabilities and older persons, in Article 2 of the Regulation on the Performance and Functioning of the Public Sector by Electronic Means. [140] Spain, Ministry of the Presidency, Relations with Parliament and Democratic Memory (Ministerio de la Presidencia, las Relaciones con las Cortes y la Memoria Histórica), Royal Decree 203/2021 of 30 March 2021 approving the regulation on the performance and functioning of the public sector by electronic means (Real Decreto 203/2021, de 30 de marzo, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de actuación y funcionamiento del sector público por medios electrónicos), 30 March 2021.

The general principles of the regulation include the principle of accessibility, understood as the set of principles and techniques to be respected in the design, construction, maintenance and updating of electronic services.

The Slovenian Promotion of Digital Inclusion Act [141] Slovenia, Promotion of Digital Inclusion Act (Zakon o spodbujanju digitalne vključenosti), 28 February 2022.

guarantees access to measures promoting digital inclusion for all target groups under equal conditions. The target groups include children, pupils and students, but also job seekers (that is, economically active or inactive people or students seeking employment), pensioners and persons with disabilities.

Some countries’ legislation makes explicit provision for safeguarding measures to ensure equal access to digital public services. In Sweden, for example, a dedicated reporting system offers the option to notify authorities if accessibility needs have not been met, and to issue complaints. Moreover, public authorities must publish accessibility reports. [142] Sweden, Act (2018:1937) on accessibility of digital public services (Lag (2018:1937) om tillgänglighet till digital offentlig service), 22 November 2018, Sections 13–15; Sweden, Ordinance (2018:1938) on accessibility of digital public services (Förordning [2018:1938] om tillgänglighet till digital offentlig service), 22 November 2018, Section 5.

The design of the new Danish secure login to access digital public services placed particular emphasis on safeguarding equal access for persons with disabilities. For example, blind people or people with visual impairments have the option to use an audio code reader to enter the one-time password required to access the digital public service. [143] Denmark, Ministry of Finance (Finansministeriet), Act No. 692 of 8 June 2018 on accessibility to public organs’ websites and mobile applications (Lov nr. 692 af 8. juni 2018 om tilgængelighed af offentlige organers websteder og mobilapplikationer), 8 June 2018.

Furthermore, the Irish Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 [144] Ireland, Assisted Decision-making (Capacity) Act 2015, Act No. 64 of 2015, 30 December 2015.

promotes a Decision Support Service to assist people with limited decision-making capacity. This may become an important tool to facilitate consent and safeguarding aspects of digital public services.

These laws are primarily concerned with the protection of persons with disabilities. They address older persons only indirectly as a potential subgroup. Specific legal protection for both older persons and persons with disabilities, as groups particularly at risk of digital exclusion, could contribute to more effective safeguarding of both groups’ access to public services.

The ongoing process of digitalisation requires Member States to establish equal access to public services, without discrimination. Non-discrimination in general is the subject of national monitoring mechanisms, but age-based discrimination in access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation is not specifically monitored and remains largely undetected.

Most Member States have not designated or established a specific institution or authority to monitor complaints raised in connection with equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. Instead they rely on existing authorities and general approaches, with mechanisms that can hear complaints of discrimination based on various grounds, without specifically targeting discrimination based on age. Information on monitoring discrimination based on age, while very scarce, was found in the work of some EU Member States’ ombuds institutions or national equality bodies, or of some advisory bodies with a different main mandate. The variety of existing systems for monitoring either non-discrimination or maladministration contributes to there being no coherent mechanism for systematic evaluation and conclusions.

Complaints regarding older persons’ access to public services due to digitalisation have been captured through other means, such as older persons’ helplines or mediators for pensions.

In Portugal, Linha do Idoso is a telephone helpline for older persons, provided by the Ombudsperson's office, to report complaints or discrimination. In 2021, 136 calls regarding public services were registered, with almost half (66) referring to difficulties in accessing the digital platforms of some public services. [145] Portugal, Ombudsperson’s Office, written response, 18 May 2022.

Similarly, almost half of the Member States’ authorities – 13 out of 27 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden) – plus North Macedonia and Serbia have received complaints related to discrimination in access to digital public services, [146] Franet information.

although the majority do not specifically address age as a protected characteristic or older persons as a group at heightened risk.

In most countries, reports make general reference to difficulties in accessing public services that are undergoing digitalisation. In Belgium, for example, the 2021 annual report of the mediator/ombudsperson for the public pensions service addressed developments related to ‘digital by default’, reporting a series of problems linked to the digitalisation of tax forms and subsequent complaints. [147] Belgium, Pension Ombudsman (Médiation Pensions) (2021), Annual report 2021 (Rapport annuel 2021), Brussels, Collège des Médiateurs pour les Pensions.

In 2020, the mediation service for patient rights also highlighted problems with the confidentiality and privacy of health data, notably complaints regarding unauthorised access to e-health records, undisclosed e-access records and sharing of sensitive psychiatric data, with a particular focus on care homes and older patients. [148] Belgium, Verhaegen, M.-N., Ombelet, S., Van Hirtum, T., Deseyn, B., Martin, A. and Van Gompel, E. (2021), Annual report 2020 (Rapport Annuel 2020), Brussels, Federal Ombudsman Service for Patients’ Rights (Service de médiation fédéral ‘Droits du patient’).

The French ombudsperson, the Defender of Rights, addressed difficulties in access to public services induced by the digitalisation of public services, but in a general way by referring to the complaints received, without providing any figures. [149] France, Defender of Rights (Défenseur des droits) (2022), Annual activity report 2021 (Rapport annuel d’activité 2021), Paris Cedex.

Some countries reported significant increases in complaints over the past three years. That may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated the digitalisation of everyday life. Important steps towards better reporting systems on age discrimination in access to public services involve measures that increase people’s awareness of their rights, and help and encourage them to report complaints.

All EU Member States, North Macedonia and Serbia have national policies, strategies, action plans or comparable policies related to digitalisation in place, FRA’s mapping shows. As Table 2 outlines, countries use different approaches to implement non-discrimination in their policy framework documents. These mirror the approaches applied in national legislative frameworks. Some of the countries explicitly mention non-discrimination but without concrete enforcement measures (see Section 3.2.1 Addressing age-based digital exclusion in law), and a very limited number of countries explicitly recognise non-discrimination (see Section 3.2.2 Addressing disability-based digital exclusion in law).

Twelve countries do not mention or recognise non-discrimination in their policy documents related to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation (see Table 2, comparison of approaches 1 and 2). Although they do not mention it explicitly, these 12 countries also have to observe non-discrimination as a fundamental principle of EU law and may address it in general anti-discrimination legislation.

Table 2 – The role of policy frameworks in ensuring equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation

|

Country |

National policy framework(s): digital strategy, action plan or comparable policy/ies in place |

Approach 1: Explicit mention of equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation

|

Approach 2: Explicit recognition of non-discrimination

|

Approach 3: Retaining offline public service options in policy documents

|

|

Austria |

|

|

|

|

|

Belgium |

x |

|

|

|

|

Bulgaria |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Croatia |

|

|

|

|

|

Cyprus |

|

|

x |

|

|

Czechia |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Denmark |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Estonia |

x |

|

|

|

|

Finland |

x |

|

|

|

|

France |

|

|

x |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

|

|

|

Greece |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Hungary |

|

|

|

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

x |

|

|

Italy |

x |

|

|

|

|

Latvia |

|

|

|

|

|

Lithuania |

x |

|

|

|

|

Luxembourg |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Malta |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

Poland |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Portugal |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Romania |

|

|

|

|

|

Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

Slovakia |

x |

|

|

|

|

Slovenia |

|

|

|

|

|

Sweden |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

North Macedonia |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Serbia |

x |

x |

|

Sources: Franet (2022), based on information provided in Franet country documents ‘Ageing in digital societies: Enablers and barriers to older persons exercising their social rights’ and on the national policy documents and plans adopted and in effect as of 31 May 2022.

Seventeen of the 29 countries covered in the research have national policy frameworks that explicitly mention equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. In the rest, the national policy frameworks do not address equal access explicitly. Some mention it vaguely or refer indirectly to non-discrimination as an underlying principle when it comes to digitalised public services.

Equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation is evident in the national programme ‘Digital Bulgaria 2025’. It defines as one of its goals (goal 11) the creation of conditions for equal access to digital public services for all social groups by effectively implementing general accessibility requirements and ensuring that certain principles and measures are respected when creating, maintaining and updating the websites and mobile applications of public sector organisations. [150] Bulgaria, Ministry of Transport, Information Technology and Communications (Министерство на транспорта, информационните технологии и съобщенията) (2019), National programme ‘Digital Bulgaria 2025’ (Национална програма ‘Цифрова България 2025’), Sofia, p. 36.

The Portuguese Strategy for the Reorganisation of Government Services [151] Portugal, Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 55-A/2014, that approves the strategy for the reorganisation of public customer care services (Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.º 55-A/2014, que aprova a Estratégia para a Reorganização dos Serviços de Atendimento da Administração Pública), 15 September 2014.

promotes geographical, economic and social cohesion. In part, that involves providing the population with equal conditions and access to services, regardless of their geographical location or “social vulnerabilities”. Older persons and persons with disabilities were recognised as most at risk of digital exclusion because of insufficient digital skills or difficulties in dealing with new technologies. Therefore, some measures were set out to protect the right to equal access to government services.

The Belgian Digital Ownership Plan makes general reference to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation. That is the action plan of the Brussels Region for 2021–2024 to reduce inequalities in access to, use of and knowledge of digital tools. [152] Belgium, Brussels Region (Région de Bruxelles-Capitale), Digital ownership plan for the Brussels-Capital Region: 2021–2024 (Plan d’appropriation numérique pour la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale: 2021–2024), Brussels.

In ‘Digital Czechia’, the only reference to the right to equal access to public services is its emphasis on the process of standardising the services provided and thus making the range of services more transparent and more easily available for quality assessment. [153] Czechia, Dzurilla, V. and the Digital Czechia Team (2018), Digital Czechia (Digitální Česko), Prague, p. 13.

In Denmark, the national policy framework mentions generally that efforts towards digitalisation should respect citizens’ rights under national law and take care of citizens who are digitally excluded and citizens with disabilities. [154] Denmark, Agreement on digitalisation-ready legislation (Aftale om digitaliseringsklar lovgivning), 16 January 2018, p. 2.

One of the core principles of the Italian strategy Digital Republic [155] Italy, Repubblica Digitale (2020), National strategy for digital competence: Operational plan (Strategia nazionale per le competenze digitali: Piano operativo).

is “ensuring inclusive and accessible services”. That means that public administrations must design digital public services that are inclusive and meet the diverse needs of people and territories. Luxembourg’s Electronic Governance Strategy 2021–2025 [156] Luxembourg, Ministry for Digitalisation (Ministère de la Digitalisation) (2021), Electronic governance strategy 2021–2025 (Stratégie Gouvernance électronique 2021–2025), Luxembourg.

recognises the right to equal access to public services that are undergoing digitalisation, regardless of individuals’ competencies and devices.

All 27 Member States, as well as North Macedonia and Serbia, address vulnerable groups generally in their national strategies related to digitalising public services. Seventeen national digitalisation policies address equal access to digital public services, and in five countries (Bulgaria, [157] Bulgaria, Ministry of Transport, Information Technology and Communications (Министерство на транспорта, информационните технологии и съобщенията) (2019), National programme ‘Digital Bulgaria 2025’ (Национална програма ‘Цифрова България 2025’), Sofia.

North Macedonia, [158] North Macedonia, Ministry of Information Society and Administration (Министерство за информатичко општество и администрација) (2018), Strategy and action plan for public administration reform 2018–2022 (Стратегија за реформа на јавната администрација 2018–2022 година); North Macedonia, Ministry of Information Society and Administration (Министерство за информатичко општество и администрација) (2021), North Macedonia national ICT strategy 2021–2025 (Северна Македонија Национална стратегија за ИКТ 2021–2025), Skopje.

Poland, [159] Poland, Act on electronic delivery(Ustawa o doręczeniach elektronicznych), 18 October 2020.

Serbia [160] Serbia, EGovernment Development Programme in the Republic of Serbia for the period from 2020 to 2022 with the Action Plan for its implementation: 85/2020-40 (Програм развоја електронска управа во Република Србији за период од 2020. до 2022 година са Акционим планом за његово спровођење), 16 June 2020.

and Sweden [161] Sweden, Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (Näringsdepartementet) (2017), National digitalisation strategy (Digitaliseringsstrategin), N2017/03643/D, Stockholm.

) the national policy instruments explicitly recognise the principle of non-discrimination in accessing public services. Only Poland, Serbia and Sweden specifically address older persons.

For example, the national programme ‘Digital Bulgaria 2025’ [162] Bulgaria, Council of Ministers (2019), National Programme Digital Bulgaria 2025, (Национална програма „ЦифроваБългария 2025).

recognises equal access to digital public services in two of its guiding principles, namely the principle of inclusion and accessibility and the principle of social participation and digital inclusion. It defines the principle of inclusion and accessibility as the obligation of public authorities to design their electronic services to be socially inclusive and to respond to diverse needs, including the needs of older persons and persons with disabilities. The principle of social participation and digital inclusion requires that all European citizens, including disadvantaged groups and citizens with disabilities, and civil society organisations can participate and benefit fully from digital opportunities, unconditionally and without discrimination. [163] Bulgaria, Council of Ministers (Министерски съвет) (2021), Updated strategy on the development of e-government in the Republic of Bulgaria for the period 2019–2025 (Актуализирана стратегия за развитие на електронното управление в Република България 2019 – 2025 г.), Sofia.

In Poland, [164] Poland, Council of Ministers (2022), European funds for digital development 2021–2027: Draft programme adopted by the Council of Ministers on 5 January 2022 (Fundusze Europejskie na Rozwój Cyfrowy 2021–2027: Projekt Programu przyjęty przez RM 5 stycznia 2022 r.), Warsaw.

the draft programme adopted by the Council of Ministers mentions people vulnerable to digital exclusion owing to their age, health conditions and disabilities. Moreover, to achieve sustainable social and economic development, it is necessary to ensure that women and men enjoy equal participation in all spheres of social life, regardless of their ethnic origin, age, health condition, residence, economic status, parental status, religion or worldview, sexual orientation, etc. The Swedish National Digitalisation Strategy clearly sets out that “all people, women and men, girls and boys, regardless of social background, functional ability and age, must be offered the opportunity to take part in digital information and services from the public sector and participate in an equal way in society.” [165] Sweden, Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (Näringsdepartementet) (2017), National digitalisation strategy (Digitaliseringsstrategin), N2017/03643/D, Stockholm.

Policy frameworks in nine countries (Cyprus, [166] Cyprus, Ministry of Communications and Works Department of Electronic Communications (2012), Digital strategy for Cyprus, Nicosia.

Czechia, [167] Czechia, Dzurilla, V. and the Digital Czechia Team (2018), Digital Czechia, (Digitální Česko), Prague.

Denmark, [168] Denmark, Digitisation Partnership (Digitaliseringspartnerskab) (2021), Report on visions and recommendations to Denmark as a digital pioneer country (Visioner og anbefalinger til Danmark som et digitalt foregangsland).

Greece, [169] Greece, Ministry of Digital Governance (Υπουργείο Ψηφιακής Διακυβέρνησης) (2021), Digital transformation bible 2020–2025(Βίβλος Ψηφιακού Μετασχηματισμού 2020–2025), Kallithea.

France, [170] France, Société Numérique (n.d.), ‘Writing tomorrow’s digital society together’ (‘Ecrire ensemble la société numérique de demain’).

Ireland, [171] Ireland, Department of the Taoiseach (2022), Harnessing digital – The Digital Ireland Framework.

Luxembourg, [172] Luxembourg, Ministry for Digitalisation (Ministère de la Digitalisation) (2021), Electronic governance strategy 2021–2025(Stratégie Gouvernance électronique 2021–2025), Luxembourg; Luxembourg, Ministry for Digitalisation (2021), National action plan for digital inclusion – For a digitally inclusive society, Luxembourg.

Malta [173] Malta, Office of the Principal Permanent Secretary (2021), Achieving a service of excellence: A 5-year strategy for the public service, Valletta.

and Portugal [174] Portugal, Minister for the Economy and the Digital Transition (Ministro da Economia e da Transição Digital) (2020), Portugal digital: Portugal’s action plan for digital transition.

) emphasise the importance of retaining offline public service options for those who cannot or do not want to engage with public services digitally.

The Czech policy on client-oriented public administration 2030 [175] Czechia, Ministry of Interior (Ministerstvo vnitra) (2019), Client-oriented public administration 2030 (Klientsky orientovaná veřejná správa 2030).

underlines that “the possibility of offline access will be maintained for those groups of people who do not want or cannot communicate electronically”. In Luxembourg, [176] Luxembourg, Ministry for Digitalisation (Ministère de la Digitalisation) (2021), National action plan for digital inclusion – For a digitally inclusive society, Luxembourg, p. 11.

the National Action Plan for Digital Inclusion outlines various initiatives to ensure equal treatment of all, including of older persons. Among other things, it highlights that analogue alternatives to digital solutions must remain guaranteed.

The Portuguese Programme for Accessibility to Public Services and on Public Roads [177] Portugal, Ordinance 200/2020, which creates and regulates the programme of accessibility to public services and on public roads (Portaria 200 /2020, que cria e regulamenta o Programa de Acessibilidades aos Serviços Públicos e na Via Pública), 19 August 2019.

encourages, among other aspects, offline access to public services, specifically recognising groups that would benefit from such measures, such as persons with disabilities and all those who cannot, will not, or do not know how to use digital devices. Similarly, the French National Strategy for the Guidance of Public Policy [178] France, Société Numérique (n.d.), ‘Writing tomorrow’s digital society together’ (‘Ecrire ensemble la société numérique de demain’).

obliges administrations to implement efficient telephone reception service for users by 2022.

The Digital Ireland Framework commits to ensuring that no group within society is left behind. Service delivery is to be user-focused, and assisted digital support will be available where appropriate. [179] Ireland, Department of the Taoiseach (2022), Harnessing digital – The Digital Ireland Framework.

As part of its public sector digitalisation strategy 2011–2015, [180] Denmark, Digitisation Partnership (Digitaliseringspartnerskab) (2021), Report on visions and recommendations to Denmark as a digital pioneer country (Visioner og anbefalinger til Danmark som et digitalt foregangsland).

Denmark adopted a legal framework on mandatory digital self-service. Apart from various other measures, citizens encountering problems using the digital service should receive support through informative videos and telephone services, ITC courses for older citizens and one-on-one guidance. The Cypriot Digital Strategy for 2025 sets out the creation of an “open, democratic and inclusive digital society” as one of its four strategic objectives. [181] Cyprus, Deputy Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digital Policy (2020), Digital Cyprus 2025.

The policy documents of 12 Member States address specific population groups at risk of being digitally excluded. The same number address these specific population groups in national laws. However, as Table 3 indicates, one or more policy documents on digitalising public policies in all the countries explicitly refer to persons with disabilities and older persons. In comparison, only seven Member States explicitly refer to older persons in national legal instruments.

National policy documents also mention a range of other groups with members who might have a higher risk of digital exclusion than others. Examples include children and young people, women, people living in rural areas, foreign nationals and migrants, ethnic minority groups, people with low educational attainment, low-income populations, prisoners, unskilled workers and people living in care homes. For example, in Belgium, the Brussels Region’s Digital ownership plan for 2021–2024 identifies six groups needing special support: job seekers, young people, older persons, persons with disabilities, the needy and disadvantaged, and women. [182] Belgium, Brussels Region (Région de Bruxelles-Capitale), Digital ownership plan for the Brussels-Capital Region: 2021–2024 (Plan d’appropriation numérique pour la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale: 2021–2024), Brussels.

The Greek Digital Transformation Bible outlines the implementation of the national strategy. It explains how the need to support vulnerable population groups in acquiring digital skills and becoming familiar with new technologies is at the heart of the government’s strategy. The policy framework explicitly refers to persons with disabilities and older persons as well as women and unemployed people. [183]

Greece, Ministry of Digital Governance (Υπουργείο Ψηφιακής Διακυβέρνησης) (2021), Digital Transformation Bible 2020–2025 (Βίβλος Ψηφιακού Μετασχηματισμού 2020–2025), Kallithea.

Only Austria, Germany and Sweden do not explicitly detail population groups at risk of digital exclusion in current policy documents, although the Swedish National Digitalisation Strategy explicitly recommends introducing a ‘zero vision’, meaning that no one should be excluded from the digital society.

In Austria, [184] Austria, Digital Austria (n.d.), ‘Austria’s digital action plan: Shaping digitisation together’ (‘Digitalen Aktionsplan Austria: Digitalisierung gemeinsam gestalten’).

the Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs has published the Digital Action Plan for Austria. It does not provide operational information on any of the visions outlined and also does not explicitly mention groups at risk of digital exclusion.

The plan for a digital Germany promotes the further implementation of the Online Access Act. [185] Germany, Federal Government Commissioner for Information Technology (2020), ‘The nine-point plan for a digital Germany’, (9-Punkte-Plan für ein digitales Deutschland), 15 July 2020.

However, the strategy only mentions that digital access to the administration must be designed in a barrier-free way. It gives further information. [186] Germany, Federal Government (Bundesregierung) (2021), ‘Shaping digitalisation: implementation strategy of the Federal Government’, Digitalisierung gestalten – Umsetzungsstrategie der Bundesregierung, June 2021, Berlin.

Although Sweden [187] Sweden, Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (Näringsdepartementet) (2017), National digitalisation strategy (Digitaliseringsstrategin), N2017/03643/D, Stockholm.

does not explicitly mention older persons to be under threat of digital exclusion, the government understands digital exclusion factors and underlines the need to continue research so that the implementation of the policy can be based on evidence.

Table 3 – Population groups vulnerable to digital exclusion as indicated in national policies

|

Country |

Population groups vulnerable to digital exclusion as indicated in national policies |

|||

|

Vulnerable population groups in general |

Persons with disabilities |

Older persons |

Other population groups * |

|

|

Austria |

x |

|

|

|

|

Belgium |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Bulgaria |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

Croatia |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

Cyprus |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

Czechia |

|

x |

x |

x |

|

Denmark |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

Estonia |

x |

|

|

x |

|

Finland |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

France |

x |

|

|

x |

|

Germany |

x |

|

|

|

|

Greece |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Hungary |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Ireland |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Italy |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Latvia |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Lithuania |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Luxembourg |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Malta |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Netherland |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Poland |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Portugal |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Romania |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Slovakia |

|

x |

x |

x |

|

Slovenia |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Spain |

x |

|

|

x |

|

Sweden |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

North Macedonia |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Serbia |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Total |

27 (25 + 2) |

21 |

20 |

22 |

Sources: Based on explicit mentions in national policy document (national plan or strategy related to digitalisation) of population groups potentially at risk of digital exclusion, as outlined in Franet country documents ‘Ageing in digital societies: Enablers and barriers to older persons exercising their social rights’.

Notes:

- Countries included are EU-27 plus North Macedonia and Serbia

- Data collected by 31 May 2022.

* Other population groups include, for example, job seekers, young people, and women, as addressed explicitly in the respective national policy documents.

According to the Council conclusions on human rights, participation and well-being of older persons in the era of digitalisation in 2020, [188] Council of the European Union (2020), Conclusions on human rights, participation and well-being of older persons in the era of digitalisation in 2020, Brussels, 9 October 2020

national policies on digitalising public services are supposed to address digital exclusion of older persons or other vulnerable groups in an inclusive way. However, some laws, for instance in Denmark, [189] Denmark, Digitisation Partnership (Digitaliseringspartnerskab) (2021), Report on visions and recommendations to Denmark as a digital pioneer country (Visioner og anbefalinger til Danmark som et digitalt foregangsland).

require people to apply for an official exemption from using digital public services, for example because of a disability or lack of digital literacy.

The Recovery and Resiliency Facility entered into force on 19 February 2021. [190] European Commission (n.d.), ‘The Recovery and Resilience Facility’. The European Commission adopted it as part of a wide-ranging response to mitigate the economic and social impact of the coronavirus pandemic. It should also contribute to making European economies and societies more sustainable, resilient and better prepared for the challenges and opportunities of the green and digital transitions, as the European Digital Decade policy programme also underlines. The facility finances reforms and investments in Member States from the start of the pandemic in February 2020 until 31 December 2026.

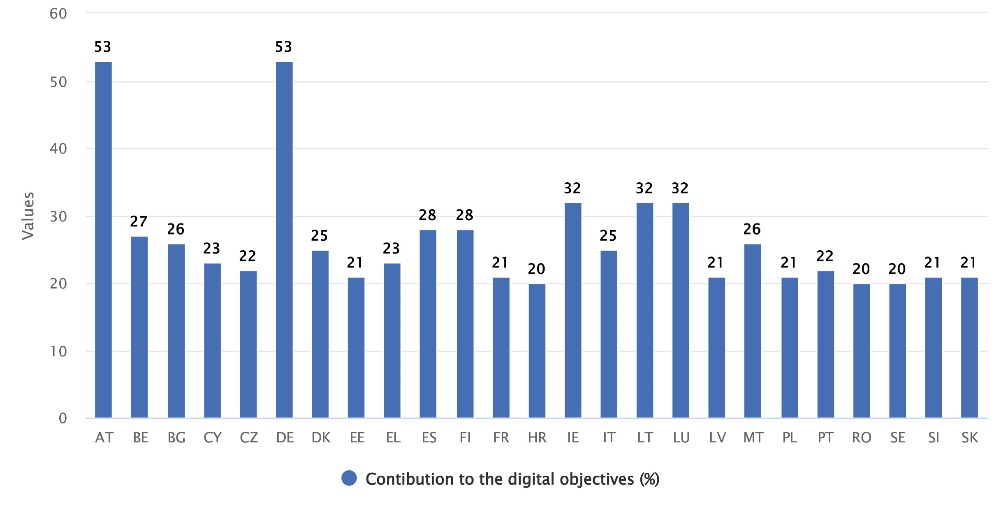

The Council of the European Union has approved 25 EU Member States’ national recovery and resilience plans (NRRPs). All of them fulfil the minimum requirement of dedicating 20 % of the total allocation to measures contributing to the digital transition or to addressing the challenges resulting from it (see Figure 5). Of this amount of EUR 127 billion, 37 % is dedicated to the digitalisation of public services and government processes and 17 % to the development of basic and advanced digital skills. [191] European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022: Thematic chapters, Brussels, available at ‘Download European Analysis 2022 (.pdf)’. The NRRPs for Hungary and the Netherlands were not approved within the same timeline and were not evaluated in the first year of implementation.

Figure 5 – Share of estimated expenditure on digital objective in the 25 RRP approved by the Council

Source: European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022: Thematic chapters, Brussels, available at ‘Download European Analysis 2022 (.pdf)’

Digitalisation of public services is a priority in 24 of the 25 Council-approved NRRPs. Only Estonia [192] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Estonia’s national recovery and resilience plan’. does not focus on the digitalisation of public services, as it is already a leader in e-government.

The effort on promoting digitalisation varies across Member States. Two countries, Austria [193] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Austria’s national recovery and resilience plan’. and Germany, [194] Germany, Federal Ministry of Finance (Bundesministerium der Finanzen) (2021), German Recovery and Resilience Plan (Deutscher Aufbau- und Resilienzplan), p. 10. have more than doubled the required allocation to 53 %. However, no funds out of the allocated amount appear to be specifically allocated to the digital inclusion of older persons in the Austrian and German NRRPs.

A positive example of preparation work and involvement of stakeholders to address digitalisation is Slovenia. Its NRRP contains the provision that electronic services must be developed in cooperation with various stakeholders, including older persons, young people and persons with disabilities. [195] European Commission (n.d.), ‘Slovenia’s national recovery and resilience plan’.

Out of 25 Member States’ NRRPs, 10 explicitly refer to vulnerable population groups, although many refer to their vulnerability in the context of COVID-19. Nine Member States specifically mention older persons as a population group that may be at risk of digital exclusion (Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania and Slovakia). [196] European Commission (2022), Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022: Thematic chapters, Brussels, available at ‘Download European Analysis 2022 (.pdf)’. These countries also allocate funding for the social inclusion of older persons. The Slovakian NRRP contains a subcomponent aiming to improve older persons’ digital skills and access to digital services and aims to increase social inclusion. [197] Slovakia, Government of the Slovak Republic (Vláda SR) (2021), ´Draft recovery and Resilience Plan for the Slovak Republic´, (Návrh Plánu obnovy a odolnosti Slovenskej republiky), 26 April 2021; Slovakia, Government of the Slovak Republic (Vláda SR) (2021), ‘Draft recovery and resilience plan for the Slovak Republic Component 17: Digital Slovakia’ (Komponent 17 Digitalne Slovensko), 26 April 2021, p.55.

The NRRPs allocate 17 % to develop basic and advanced digital skills. However, none of them includes a multi-country project related to skills education, according to the European Commission’s annual assessment in its DESI 2022. To reach the Digital Decade policy programme [198] European Commission (2023), ‘Digital Decade policy programme 2030’. target of at least 80 % of people aged 16 to 74 with at least basic digital skills by 2030, different national programmes have been drafted and implemented.

Still, there are some relevant national practices. In Belgium, [199] Belgium, Office of the Secretary of State for Recovery and Strategic Investments, in charge of Scientific Policy (Cabinet du Secrétaire d’Etat à la Relance et aux Investissements Stratégiques, en charge de la Politique Scientifique) (2021), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Plan national pour la reprise et la résilience), Brussels. for example, the NRRP allocates EUR 585 million for training and education. EUR 450 million of that focuses on digital inclusion, and vulnerable groups are prioritised as target groups for training.

Some countries delegate the task of education and training to other stakeholders. The Bulgarian NRRP allocates EUR 1.18 billion for enhancing digital skills. The largest portion, EUR 319 million, goes to NGOs that design and implement digital literacy projects. [200]Bulgaria, Council of Ministers (Министерски Съвет На Република Българ) (n.d.), ‘National Recovery and Resilience Plan’ (‘Национален план за възстановяване и устойчивост’).

Overall, the 25 NRRPs approved by the Council broadly recognise the risk of digital exclusion for vulnerable groups, but only nine of them explicitly address older persons.