6

Juli

2023

Preventing and responding to deaths at sea: what the European Union can do

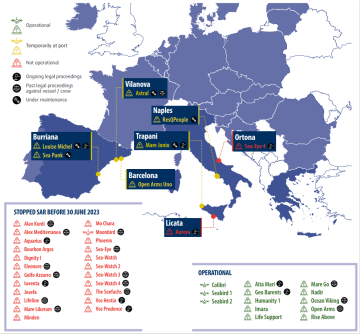

Following yet another recent tragic shipwreck and loss of life in the Mediterranean, this short report sets out examples of actions the EU could take to meet its obligations to protect the right to life and prevent more deaths at sea. As part of the work that the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) does on upholding fundamental rights in asylum and return procedures, this report calls for better protection for shipwreck survivors, and prompt and independent investigations. It sets out measures that EU Member States should take to improve search and rescue efforts and provide legal pathways to safety to prevent deaths at sea.

Related