CSOs, human rights defenders and other activists continued to face threats and attacks in the EU from both private and public players in 2022.[114] See Franet’s country studies on civic space for the 27 Member States, the Civic Space Watch website and the Civicus Monitor.

Both EU CSOs and human rights defenders in exile in EU Member States are affected., Human rights defenders in exile can also be affected by acts of transnational repression.

International human rights law guarantees people the rights to life[115] Article 6 ICCPR; Article 2 ECHR.

, liberty and security[116]Article 9 ICCPR, Article 5 ECHR.

; to participate in public affairs[117] Article 25 ICCPR.

; and to be free from any undue interference in their enjoyment of the freedoms of expression[118] Article 19 ICCPR, Article 10 ECHR.

, assembly[119] Article 21 ICCPR, Article 11, ECHR.

and association[120] Article 22 ICCPR, Article 11, ECHR.

. In the EU, similar entitlements are reflected in the Charter. The Victim’s Rights Directive requires Member States to pay particular attention to "victims who have suffered a crime committed with a bias or discriminatory motive which could, in particular, be related to their personal characteristics", which may be the case for CSO activists. [121]Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA, Art. 22

The Council of the European Union recently asked Member States to; ‘[p]rotect CSOs and human rights defenders from, inter alia, threats, attacks, persecution of critical voices and smear campaigns targeting organisations, staff and volunteers by active means, such as by taking targeted actions to address these issues, by establishing monitoring mechanisms to prevent such threats, by ensuring the prompt identification, reporting, investigation and follow-up on such incidents, and by putting in place dedicated support services for civil society actors’.[122] Council of the European Union (2023), Council Conclusions on the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights; The role of the civic space in protecting and promoting fundamental rights in the EU, 14 March 2023, para. 14.

This followed the European Commission’s 2022 annual report on the application of the Charter and is in line with the Council of Europe’s Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)11 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States. [123] Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers (2018), Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)11 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the need to strengthen the protection and promotion of civil society space in Europe, 28 November 2018.

CSOs and human rights defenders continue to experience threats and attacks across all EU Member States. Overall, the vast majority of respondents from EU Member States indicated in FRA’s consultation that they had faced some form of threat and attack in 2022.

Of the 168 respondents who provided information about perpetrators of these attacks, around half (48 %) identified a state/public actor as the main perpetrator of attacks against their organisation, whereas nearly half (46 %) suspected or knew that the perpetrators were non-state/private actors. Moreover, regarding the 193 responding CSOs who provided information about specific themes, the majority believe that the attacks were linked to the activities and issues the organisations worked on (87 %). 175 respondents answered questions about whether the attacks were related to their specific funding sources, with 30 % agreeing. [124] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation.

Such threats and attacks include actions both against organisations and their infrastructure and against their staff or volunteers. They include online and offline intimidation and harassment, negative public statements and smear campaigns, verbal threats, and legal and physical attacks.[125] FRA’s 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2018 civic space consultations.

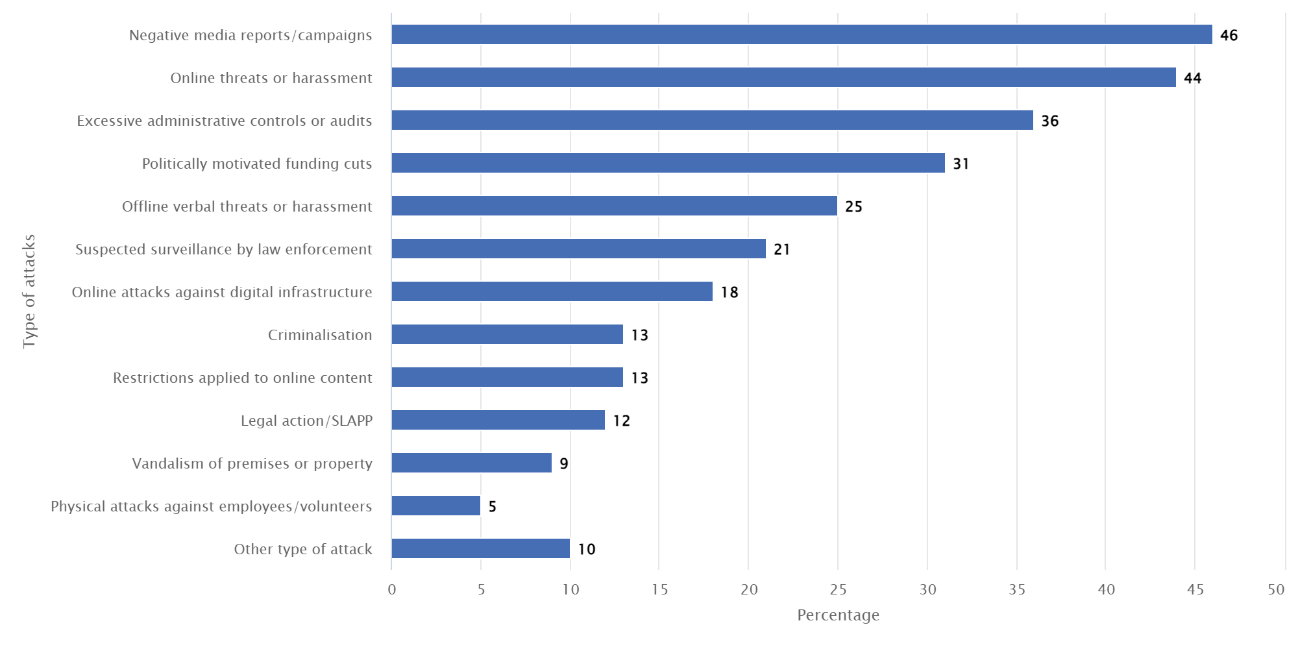

In several Member States, CSOs reported a climate of hostility towards them and human rights defenders: nearly half of CSOs responding to FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation report that media outlets or state actors initiated smear campaigns (see Figure 5).[126] FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation.

Figure 5 – CSOs’ experiences of threats and attacks in the EU in 2022 (%)

The bar chart shows the different types of threats and attacks experienced and their frequency. The type of threat or attack that occurred most often was ‘Negative media reports/campaigns’ which was experienced by 46% of organisations. The second most frequent threat or attach experienced was ‘Online threats or harassment’ which was experienced by 44% of organisations. Other threats or attacks which were experienced by over 30% of organisation were ‘Excessive administrative controls or audits’ which was experienced by 36% of organisations and ‘Politically motivated funding cuts’ which was experienced by 31% of organisations.

Notes: Question: “In the last 12 months, has your organisation, or any of your employees/volunteers, experienced any of the following [types of attacks]?” N = 301.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

These findings are consistent with the findings of international organisations and CSOs who follow the situation of CSOs and human rights defenders. [127] For example, European Commission (2022), A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU 2022 Annual Report on the Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, COM/2022/716 final; OECD (2022), The protection and promotion of civic space: Strengthening alignment with international standards and guidance.

In some Member States, governments, politicians and high-level officials highlight the vital role of human rights defenders and other civil society actors in promoting rights and ensuring accountability.

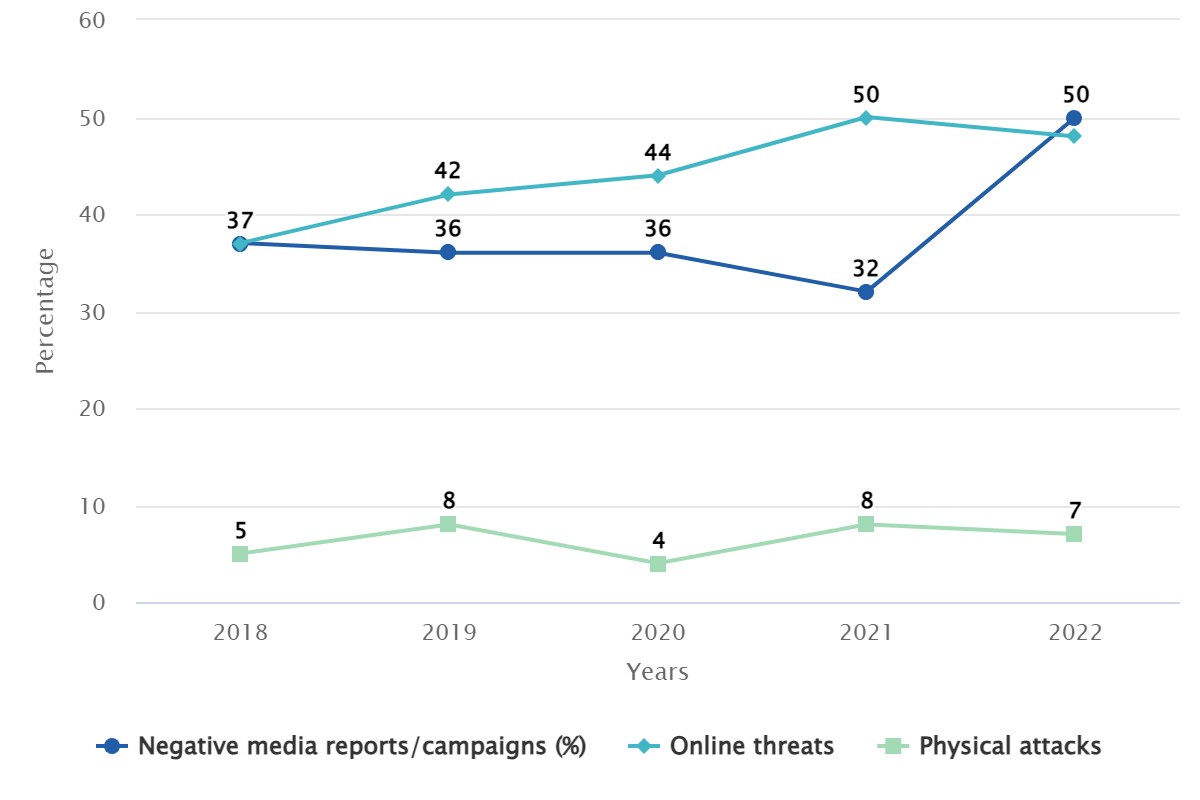

Figure 6 shows developments over time in the percentage of CSOs facing negative media reports/campaigns, online verbal threats and physical attacks.

Figure 6 – Developments in CSOs experiencing threats or attacks in the EU (%)

A line chart showing the evolution between 2018 and 2022 of the percentage of organisations which experienced different types of threats or attacks. The percentage of organisations which experienced online threats increased from just below 30% to just below 50% over the period. The percentage of organisations which experienced negative media reports or campaigns remained stable between 2018 and 2020 at just below 40%, then dropped to just above 30% in 2021 then increased sharply in 2022 to 50%. The percentage of organisations which experienced physical attacks remained stable over the period at 5%.

Notes: Question: “In the past 12 months, has your organisation, or any of your employees/volunteers, experienced any of the following?” The figure includes those responding ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ to the question about negative media reports/campaigns, online verbal threats, and physical attacks.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018–2022

The results of FRA’s 2022 consultation are consistent with findings from previous years. Negative media reports and campaigns were, again, the forms of threat and attacks that responding CSOs experienced most (46 %) in 2022 (see Figure 5). Similarly, the consultation shows that online verbal threats and harassment continue to affect almost half of responding organisations. In addition, more than a third of the responding CSOs claim to have been targets of excessive administrative controls or audits.

Reports of suspected surveillance by law enforcement increased greatly, to 21 % of respondents from 7 % in 2021.[128] FRA’s 2021 and 2022 civic space consultations. At the same time, the criminalisation of and legal actions against civil society activities continue, notably SAR at sea and providing humanitarian assistance to those in need while on the move (see Section 3.2). Legal and administrative harassment, in particular through abusive prosecutions and SLAPPs, are also noted (see Section 2.2).

Threats and attacks particularly affect organisations and human rights defenders working with minority groups, those working with migrants and refugees, those working to combat racism, and those working to promote women’s rights, sexual and reproductive health and rights and LGBTIQ+ rights. The lack of a safe environment for CSOs to fulfil their functions can have an impact on the implementation of the related EU strategies.

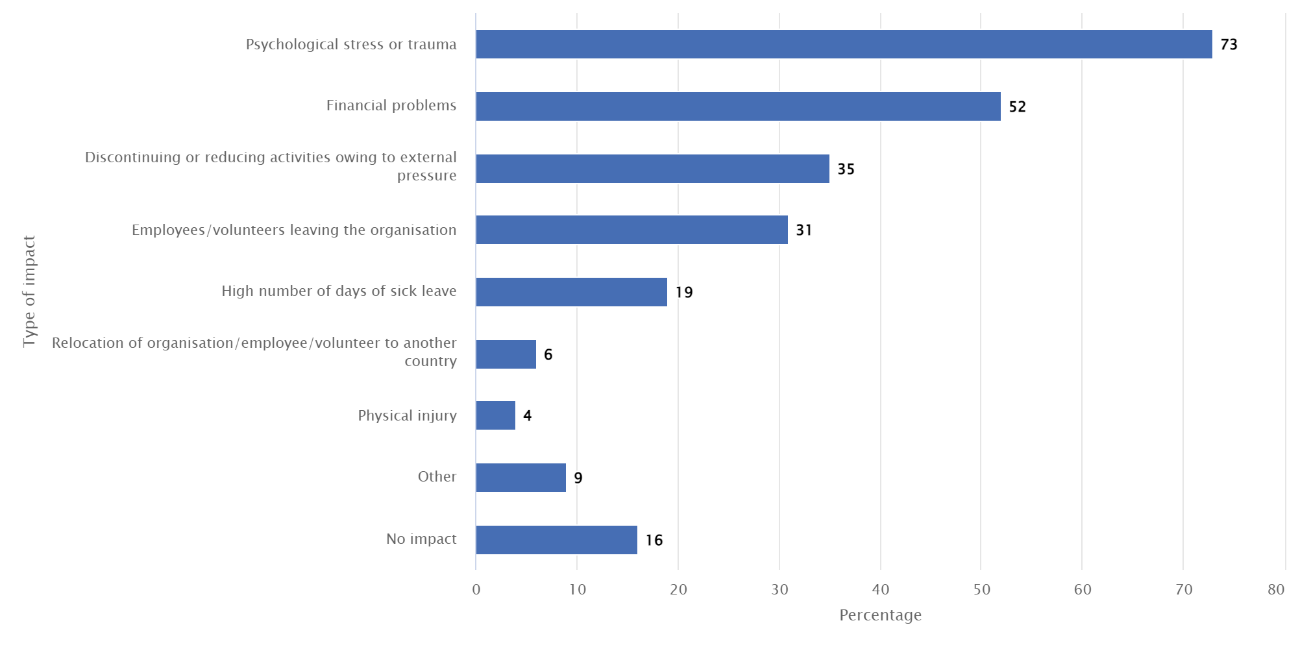

Among the consequences of such attacks for employees and volunteers are psychological stress and trauma and financial problems. The attacks can also result in the interruption or reduction of organisations’ activities as a result of external pressure, or employees leaving the organisation (Figure 7). In some cases (6 %), an organisation or an individual human rights defender even had to be relocated to another country, and 4 % had suffered physical injuries.[129] Ibid.

Figure 7 – Impact of attacks on civil society in the EU in 2022 (%)

The bar chart shows the different types of impact that attacks on organisations have. 73% of organisations suffered ‘Psychological stress or trauma’ as a result of attacks, 52% or organisations experienced financial problems as a result and 35% reported discontinuing or reducing activities. 31% or organisations reported employees or volunteers leaving the organisation and 19% said they experienced a high number of days of sick leave. 6% or organisations relocated to another country and 4% reported physical injuries.

Notes: Question: “What was the impact of these attacks in the last 12 months on your organisation and its employees/volunteers?” N = 217.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

Yet only one in five organisations reported these incidents to a competent body or the media. The main reasons respondents give for not reporting incidents is that they did not regard the incident as serious enough (52 %), they felt that nothing would come out of reporting (34 %), they lack trust in the authorities or the police (17 %) or they find it too much trouble to report an incident (17 %).

A specific development concerns attacks against human rights defenders in exile in the EU. Evidence shows that defenders from non-EU countries in exile in EU Member States face transnational repression from the governments of their home countries in the form or threats and attacks.[130] Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly (2023), Transnational repression as a growing threat to the rule of law and human rights, 23 June 2023; Freedom House (2022), Defending democracy in exile: Policy responses to transnational repression, Washington, DC, Freedom House; and Gorokhovskaia, Y., Schenkkan, N. and Vaughan, G. (2023), Still not safe: Transnational repression in 2022, Washington, DC, Freedom House. The NGO Freedom House has documented such attacks occurring in 19 EU Member States since 2014. Transnational repression can include acts such as assassination or assassination attempts, detention, unlawful deportation, rendition, assault, unexplained disappearance, credible threat and intimidation.[131] Freedom House’s database on transnational repression (not publicly available). For an overview of issues, see Gorokhovskaia, Y., Schenkkan, N. and Vaughan, G. (2023), Still not safe: Transnational repression in 2022, Washington, DC, Freedom House.

Human rights defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are facing an increasing number of challenges and risks in their work. These range from verbal threats and physical attacks to smear campaigns and increasing pressure from authorities.[132] See, in this context, Council of Europe (2022), Pushed beyond the limits: Four areas for urgent action to end human rights violations at Europe’s borders, April 2022, pp. 36–37.

The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders, in her report of July 2022, draws attention to the situation of defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers and the particular administrative, legal, practical and societal barriers they face, including in the EU.[133] OHCHR (2022), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders – Refusing to turn away: Human rights defenders working on the rights of refugees, migrants and asylum-seekers, 18 July 2022.

CSOs report facing smear campaigns that portray activists as “people smugglers” or “foreign agents”, according to evidence that FRA collected.[134] FRA (2022), Europe’s civil society – Still under pressure: 2022 update, Luxembourg, Publications Office; FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation; Franet’s country studies on civic space for the 27 Member States.

For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders raised concerns about reports of human rights defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Greece receiving hostile comments.[135] United Nations, Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders (2022), Statement on preliminary observations and recommendations following official visit to Greece, 22 June 2022.

Pressures from authorities include criminal and administrative proceedings brought against defenders.[136] See, for example, Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM) (2023), More than 100 people criminalised for acting in solidarity with migrants in the EU in 2022.

SLAPPs have targeted migrant rights defenders in at least 12 EU Member States While the overwhelming majority of cases end with the acquittal of the activists, such lawsuits have the potential to keep the activists occupied, hindering their human rights work, and have a chilling effect.[137] See, for example, CASE (2023)– Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe, SLAPPS: a threat to democracy continues to grow; Franet’s country studies on civic space for the 27 Member States; PICUM (2023), More than 100 people criminalised for acting in solidarity with migrants in the EU in 2022.A World of Neighbours webinar, 15 March 2023.

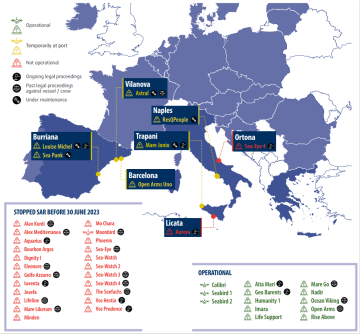

The situation of civil society players involved in SAR at sea illustrates these challenges. CSOs deploy their own SAR vessels and reconnaissance aircrafts, seeking to reduce fatalities in light of the significant numbers of people trying to enter the EU irregularly either to seek asylum or to migrate. Between January and July 2023, NGOs brought 3,777 people to Italian ports, according to the Italian Ministry of the Interior. Although this makes up only 4.24 % of all sea arrivals, NGOs made a significant contribution to reducing fatalities.[138] Italy, Ministry of the Interior (2023), Dossier of the Ministry of the Interior, 15 August 2023 – The activity of the Ministry of the Interior (Dossier Viminale 15 agosto 2023 L’attività del Ministero dell’Interno), 15 August, p. 30. Data cover January – July 2023.

In Greece, Law 4825/2021[139] Greece, Government Gazette (2021), ‘Law 4825/2021: Reform of deportation and return procedures of third country nationals, attracting investors and digital nomads, issues of residence permits and procedures for granting international protection, provisions within the competence of the Ministry of Migration and Asylum and the Ministry of Citizen Protection and other emergency provisions’ (Αναμόρφωση διαδικασιών απελάσεων και επιστροφών πολιτών τρίτων χωρών, προσέλκυση επενδυτών και ψηφιακών νομάδων, ζητήματα αδειών διαμονής και διαδικασιών χορήγησης διεθνούς προστασίας, διατάξεις αρμοδιότητας Υπουργείου Μετανάστευσης), Government Gazette A 157/4-9-2021, Article 40.

regulates the operation of NGOs within the field of competence of the Hellenic Coast Guard. It restricts independent action by NGOs and imposes conditions on their activities. The Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe expressed concern about this provision highlighting that it “may further jeopardise NGOs’ human rights activities in relation to persons arriving by sea, and severely undermine the necessary scrutiny of the compliance of the operations of the Greek Coast Guard with human rights standards”.[140] Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights (2021), Greece's Parliament should align the deportations and return bill with human rights standards, 3 September 2021.

CSOs engaged in SAR operations have been experiencing increasing pressure.[141] European Commission (2023), ‘2023 Rule of law report – Communication and country chapters’, 5 July 2023; FRA (2023), Asylum and migration: Progress achieved and remaining challenges, Luxembourg, Publications Office, pp. 9–11; CEPS (2023), ‘Policing search and rescue NGOs in the Mediterranean – Does justice end at sea?’, 24 February 2023.

As their presence is sometimes perceived as encouraging irregular arrivals, they encounter hostile attitudes and face legal proceedings and other measures aiming at blocking their activities. “Their work saves lives and protects human dignity, yet it is being repressed, undermined and obstructed by states”, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders notes.[142] Lawlor, M. (2023), ‘EU's values should dictate an ethos of hospitality’, 20 June 2023.

Since 2017, Germany, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, and Spain have initiated 63 administrative or criminal proceedings relating to civil society bodies’ SAR operations. Most are proceedings against vessels. One third are criminal proceedings against staff or crew.[143] FRA (October 2023), June 2023 update – Search and rescue (SAR) operations in the Mediterranean and fundamental rights.

These measures need to be examined in light of the broader legal framework relating to search and rescue and maritime safety. International maritime law imposes a clear obligation on vessels to assist all people in distress at sea. Both government and private vessels have a duty to assist people and crafts in distress at sea. Multiple instruments of the international law of the sea regulate this duty.[144] For an overview of the legal framework regulating the duty to provide assistance to people in distress at sea, see FRA (2013), Fundamental rights at Europe’s southern sea borders, Luxembourg, Publications Office, Chapter 2; FRA (October 2023), June 2023 update – Search and rescue (SAR) operations in the Mediterranean and fundamental rights.

Acts hindering humanitarian SAR activities which are not necessary to address risk to safety, health or the environment may violate states’ obligation to protect the right to life. In addition, deaths resulting from such acts may constitute an arbitrary deprivation of life, for which the state is responsible.[145] UN (2018), Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions: Saving lives is not a crime, 7 August 2018, paras 13–18.

Some of the rescue vessels that CSOs deploy are blocked at ports due to legal proceedings, such as vessel seizures, and cannot carry out SAR operations. The Court of Justice of the European Union recently clarified that the port state may inspect SAR ships of humanitarian organisations and may seize such vessels in the event of a clear risk to safety, health or the environment.[146] CJEU, Joined Cases C-14/21 and C-15/21, Sea Watch, 1 August 2022.

However, grey areas still remain in law as regards the permissibility of certain restrictive administrative measures that state authorities impose.

Following a discussion in late 2022, the Italian government introduced Decree-Law No. 1/2023 on urgent provisions for the management of migratory flows. The decree-law, converted into Law 15/2023, obliges ships to proceed to a designated port, often far away from the rescue area, immediately after each rescue operation – reducing thus the possibility of rescuing other groups of people in distress over the course of several days.[147] Transformed into law in early 2023: Italy, Law No. 15/2023, 24 February 2023.

In addition to criticism voiced by the European Parliament and UN bodies,[148] European Parliament (2023), Letter by Chair of the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, López Aguilar, to Commissioner Johansson, published on Twitter, 9 February 2023; OHCHR (2023), ‘Italy: Criminalisation of human rights defenders engaged in sea-rescue missions must end, says UN expert’, press release, 9 February 2023.

NGOs raised concerns that the decree-law “contradicts international law”,[149] Sea-Watch (2023), ‘Statement: New Italian government decree will cause more deaths in the Mediterranean Sea’, 5 January 2023.

slows down SAR actions, and increases the number of deaths and disappearances at sea. Those NGOs that refused to head to the designated ports or decided to rescue more groups of people in distress at sea, faced sanctions.

While the coordination of SAR activities is, in principle, the responsibility of national authorities, SAR for persons in distress at sea launched and carried out in accordance with Regulation (EU) No. 656/2014 and with international law, taking place in situations which may arise during border surveillance operations at sea is also a core element of European integrated border management.[150] Regulation (EU) 2019/1896 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2019 on the European Border and Coast Guard and repealing Regulations (EU) No. 1052/2013 and (EU) 2016/1624, OJ 2019 L 295, Art. 3 (1) (b). See also European Commission (2023), Communication establishing the multiannual strategic policy for European integrated border management – Annex I, COM(2023) 146 final, Strasbourg, 14 March 2023, Component 2, pp. 5–6.

The EU has therefore acknowledged the need for a more structured common framework for cooperation in the field of SAR and has developed a series of policy instruments concerning civil society rescue organisations. As part of the package of instruments, presented under the Pact on Migration and Asylum, Recommendation (EU) 2020/1365 addresses EU Member States with a view to reinforcing information sharing, coordination and cooperation between states and other relevant stakeholders in the field of SAR operations carried out by private vessels operated for this specific purpose. Furthermore, the recommendation aims to ensure that the fundamental rights of rescued people are guaranteed in conformity with the Charter and the principle of non-refoulment.[151] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1365 of 23 September 2020 on cooperation among Member States concerning operations carried out by vessels owned or operated by private entities for the purpose of search, and rescue activities, OJ 2020 L 317.

In 2021, the European Commission established a SAR Contact Group, to facilitate dialogue between Member States and other relevant stakeholders on the implementation of the legal framework for and the evolving practice of SAR.[152] European Commission (2021), ‘Informal Commission expert group “European Contact Group on Search and Rescue”’, 11 March 2021.

To FRA’s knowledge, two years on, there has not yet been a structured interaction between this contact group and the CSOs deploying SAR vessels and reconnaissance aircrafts.