4.1. Financial resources and budget allocation

Member States need to allocate sufficient financial and human resources to child protection systems. This will ensure the full respect, protection and fulfilment of children’s rights. Resource shortages undermine the overall performance of child protection systems, diminishing their sustainability and the quality and scope of the protection they provide.

In decentralised systems, the national, regional and local budgets fund child protection. When ensuring adequate resource allocation, it is important to identify the proportion of national and other budgets allocated to children, both directly and indirectly.

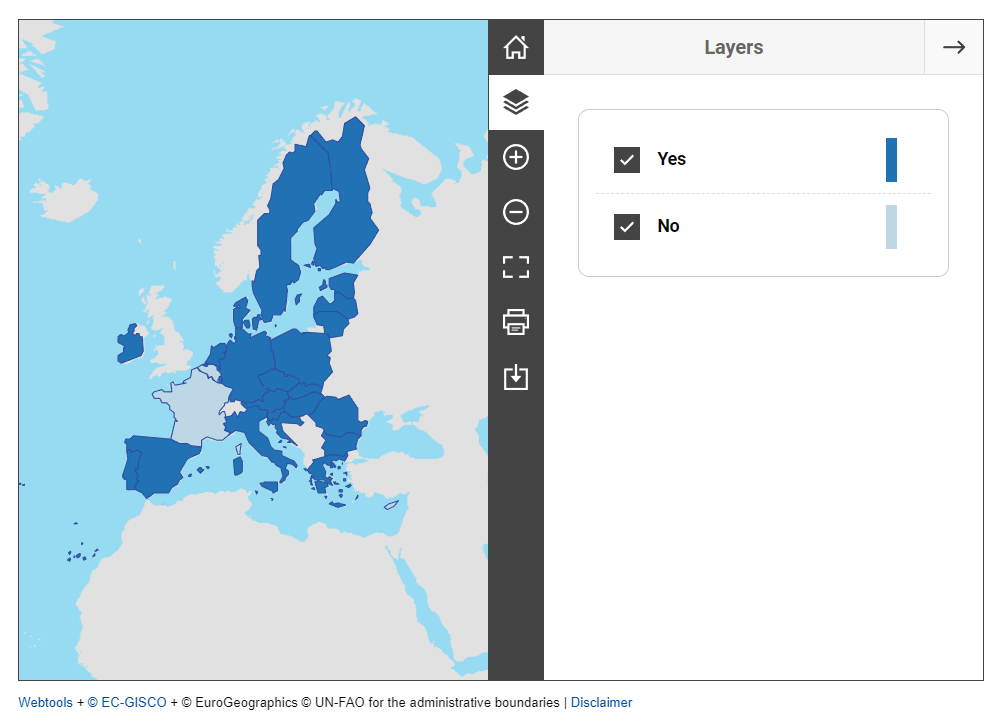

Figure 6 – Specific budget item allocated to child protection in the annual state budget

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have a specific budget item allocated to child protection in the annual state budget. 14 Member States allocate a specific budget item for child protection. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Within decentralised systems, local authorities are primarily responsible for developing child protection and family support services. Therefore, the budget national governments allocate aims to supplement local budgets.

- National budgets are often allocated based on a formula. The formula includes variables such as the number of inhabitants in a municipality and/or the number of cases involving children living there.

- Expenditure related to child protection is often not clearly visible in the state budget. It is distributed across various areas concerning children. These areas include education, social welfare, allowances and benefits, care, healthcare, justice and early childhood education and care.

- The budget allocated to child protection is very often included in overall expenditure for social policy / social welfare. However, types of expenditure listed under social expenditure vary by Member State. Typically, they include child allowances, or the budget allocated to the responsible child protection authority, but do not cover those that fall under the scopes of other ministries. The lack of a separate budget could be linked to the absence of a separate institution responsible for child protection.

- No CRC provision dictates the expenditure/budget that local authorities should devote to child protection. Nor does one dictate how expenditure should be determined. The Member States / states parties and their respective authorities have full discretion in this.

- Poor working conditions in child protection are a recurrent problem in many Member States due to insufficient human and financial resources. There is an increased risk of burnout. This appears to be leading to higher staff turnover and fewer people choosing a profession in this area. Consequently, the quality of services and protection is diminishing.

In almost half of the EU Member States, the budget allocated to child protection is not clearly visible.

Fourteen Member States allocate a specific item in their annual state budget to child protection. This applies in Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, France, Croatia, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden.

Finland introduced child-oriented budgeting as a new feature of the national budget in 2022 [4] See Penttilä, M. and Aho, J. (2022), Kuntien ja hyvinvointialueiden lapsibudjetointi ja toteumatietojen seuranta sekä raportointi: Selvityshenkilöiden raportti (Child-oriented budgeting of municipalities and wellbeing services counties, and the monitoring and reporting of outturn data: Report by rapporteurs), policy brief 2022:55, Helsinki, Publications of the Ministry of Finance, Helsinki.

. It now has a section summarising expenditure targeting children and families. Children are included in the general part of the budget.

Some Member States incorporate the budget allocated to child protection into concrete national policy measures. This is the case, for instance, in Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Romania, Finland and Sweden.

In some Member States – for example, Czechia, Germany and Poland – there are multiple budget items covering expenditure connected to child protection. This is instead of a specific budget section or item encompassing all connected expenses.

More often, the budget allocated to child protection is included in the overall expenditure for social policy and social welfare. This is the case, for example, in France, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland and Romania.

However, the types of expenditure related to child protection that are listed under social expenditure vary among Member States. They typically include child allowances or the budget allocated to the responsible child protection authority. In principle, they do not cover expenditure that falls under the scopes of other ministries.

Only Spain, France, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Hungary currently have sufficient and sustainable funding for child protection, FRA’s research shows.

In recent decades, the EU has invested millions of euro in strengthening child protection systems through a range of projects and programmes, e.g. European Social Fund+ (ESF+), European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD), Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values (CERV) programme, Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and others. The national and regional bodies in each Member State are in charge of applying for the funds available. There are periodic open calls for proposals.

The different EU funding available for the national child protection systems or specific parts of them is important, more than half of Member States say. This applies to Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Austria, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia. However, 12 Member States do not use EU funds to significantly support their child protection systems or related measures.

The European child guarantee, adopted on 14 June 2021, aims to ensure that every child in Europe at risk of poverty or social exclusion has access to certain key services in high-quality and free early childhood education and care. These are education (including school-based and out-of-school activities), healthcare, healthy nutrition and adequate housing. Member States had to submit national action plans for the implementation of the European child guarantee and appoint a national co-ordinator. The national plans focus on the activities that require improvement in a given country.

The use of funds and their assessed role in child protection systems vary. EU funds support smaller projects in most of the Member States. They have contributed to reform efforts in Estonia and Greece. In Spain, the European child guarantee contributes to desired changes to the child protection system.

Table 5 summarises the data Member States provided on the allocation of resources. The available data vary significantly. There is no harmonised approach to providing comparable data on financial resources allocated to child protection. This presents a barrier to assessing spending efficiency and addressing the needs of children in Member States.

Table 5 – Percentage of national budget spent on child protection in recent year(s), by EU Member State

|

EU Member State |

Percentage of national budget spent on child protection in recent year(s) |

|

Belgium |

Flemish community: 1.2 % of the total budget of the Flemish Region in 2022 French community: 2.71 % of the total budget of the French community in 2022 and 2.96 % in 2023 (planned) German-speaking community: EUR 7,299,000 in 2022 and EUR 7,369,000 in 2023 (percentages not available). |

|

Bulgaria |

4.7 % of gross domestic product in 2017 |

|

Denmark |

0.1 % of the expenditure of the central government (2019–2023) |

|

Estonia |

0.38 % is the proportion of children's rights expenses from the State Budget administered by the Ministry of Social Affairs |

|

Finland |

2.7 % of the total state budget in 2020 |

|

France |

1.87 % of public spending in 2020 |

|

Ireland |

1.03 % in 2022 |

|

Latvia |

0.43 % of the total national budget in 2022 |

|

Malta |

0.1 % of the government’s total recurrent expenditure in 2022 |

|

Netherlands |

0.08 % of the national budget in 2023 |

|

Spain |

Yearly average 0.9 %; 1.46 % in 2023 |

|

Sweden |

0.06 % in 2022 |

Note: Data on budget for child protection systems not available for all Member States.

Source: Franet, 2023.

Article 3(3) of the CRC states that (emphasis added):

‘States Parties shall ensure that the institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision’.

The legal and regulatory framework reflects the qualification requirements of professionals and personnel working in child protection services in most EU Member States.

Accreditation and licensing procedures are in place in some Member States. These ensure compliance with existing requirements and ensure qualified personnel are available. The procedures often include checking compliance with educational qualification and training requirements. They can include vetting procedures, such as requesting and checking criminal records.

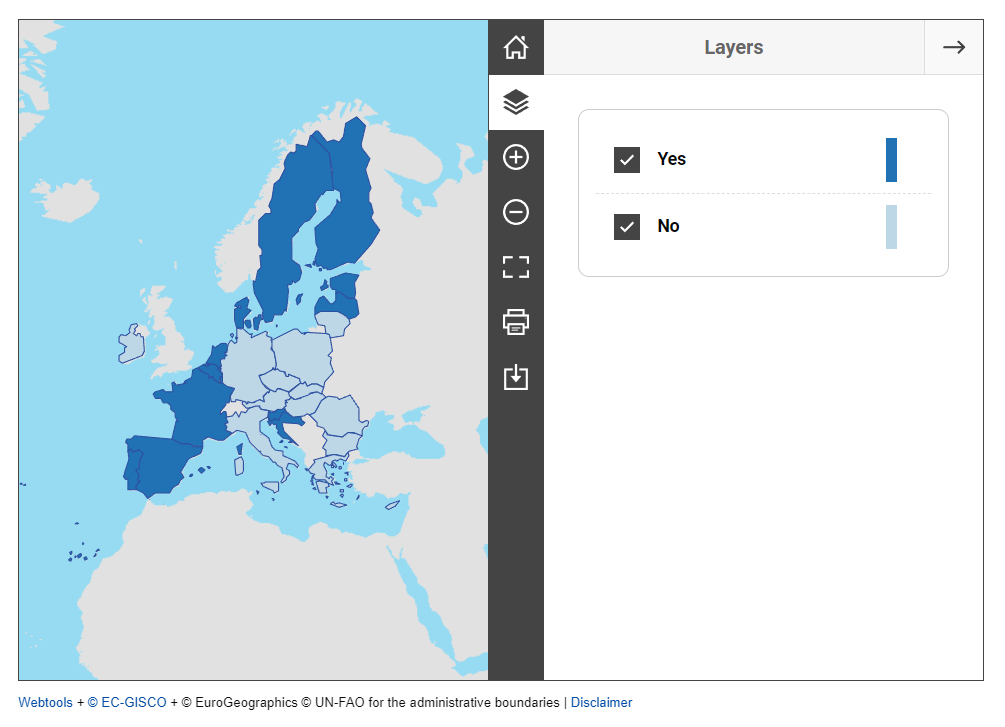

Figure 7 – Certification of social workers and compulsory training requirements

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have certification of social workers and compulsory training requirements in place. 10 Member States have certification procedures for social workers that include training requirements. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- Not all Member States have accreditation and licensing procedures for professionals in child protection.

- The accreditation and licensing procedures available are often limited to specific professional groups. They do not concern all those working with children. For example, they may not cover administrative personnel and staff involved in the daily care of children in institutions. Qualification requirements are not always sufficiently precise.

- Most Member States require people working with children to provide relevant documentation, such as criminal records. However, not all professionals must provide this documentation. Volunteers are not always as carefully vetted as professionals.

- Accreditation and licensing procedures do not always involve mandatory initial or ongoing training for professionals working with children. This includes training for administrative personnel and staff involved in the daily care of children in institutions.

- The lack of adequate training for staff involved in child protection affects over half of the Member States. It poses a serious risk to ensuring staff competence. Thus, it risks the protection, health, well-being and rights of children.

Certification and accreditation and vetting procedures vary across Member States. Spain, Malta, Austria, Portugal and Finland require vetting plus proof of an accredited diploma in social work. There is no specific training. In general, there are no provisions requiring review.

Ten Member States have certification procedures for social workers that include training requirements. This applies to Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden.

In Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden, people who are working with children must provide relevant documentation, such as criminal records. For example, in Latvia, volunteers working with children must not have criminal convictions.

In Czechia, Germany and Hungary, no certification or accreditation procedures exist for social workers. There are, however, accreditation provisions specifying mandatory training for certain professionals. These apply to child protection officers, guardians, social assistants, family assistants and child carers, for example. In Czechia, child protection workers, social workers and teachers must complete a number of hours of training per year. The content of the training is not specified.

The allocated personnel are not always competent and appropriately trained, according to 15 Member States: Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden. Only Denmark, Croatia, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland and Finland disagree. The allocated personnel are competent in the area of child protection and appropriately trained, they state.

There have been recent developments in children’s rights and child protection training in several Member States. Training activities cover diverse professionals who are working closely with children, such as judges, prosecutors, lawyers, police officers and social workers. This applies in Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland, for example.

According to Article 3(3) of the CRC (emphasis added):

‘States Parties shall ensure that the institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision’.

Vetting refers to procedures through which child protection authorities ensure that those seeking to work regularly with children have no criminal convictions that could endanger a child’s well-being and safety. This covers acts such as the sexual exploitation or sexual abuse of children. More information on EU Member States’ provisions requiring vetting can be found in the maps below.

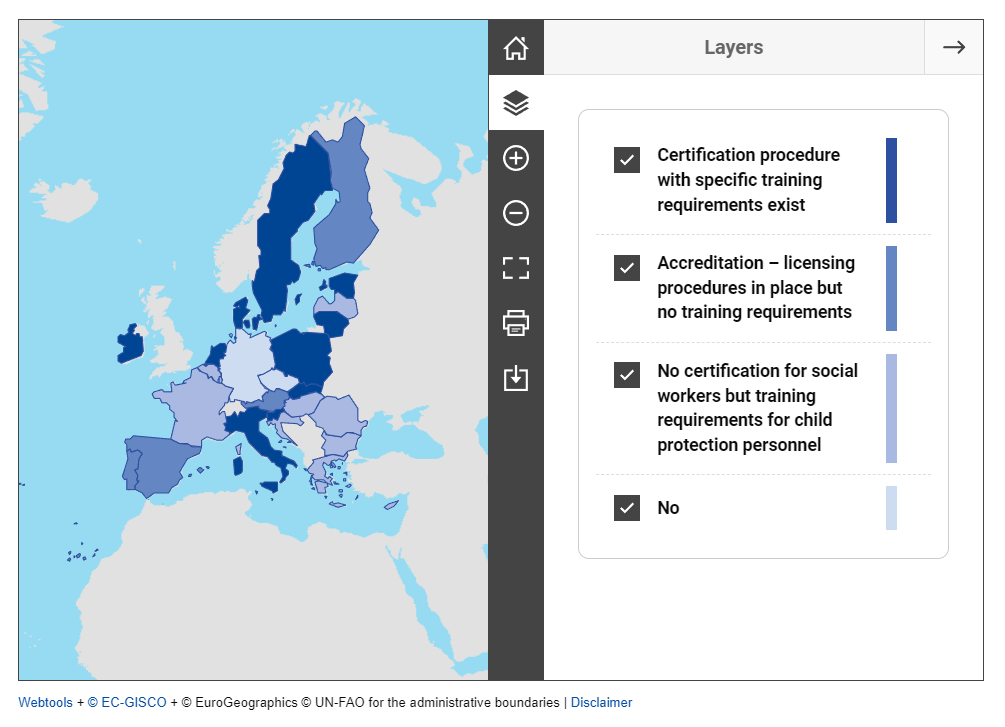

Figure 8 – Provisions requiring frequent vetting of foster families

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions requiring frequent vetting of foster families. 19 Member States have provisions for the frequency of review of foster families. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

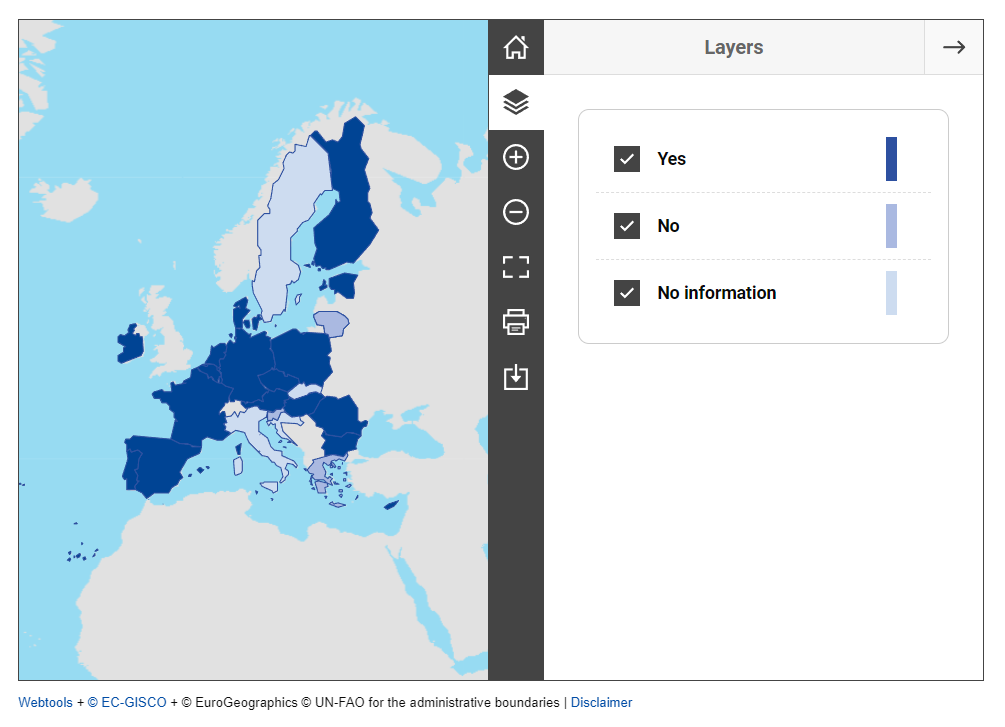

Figure 9 – Provisions requiring frequent vetting of residential care personnel

Alternative text: A map shows whether or not EU Member States have provisions requiring frequent vetting of residential care personnel. 13 Member States have provisions for the frequency of review of residential care personnel. The status for each Member State can be found in the following “Key findings” section.

Source: FRA, 2023

Key findings

- In most Member States, foster families and residential care personnel are selected in accordance with appropriate rules and they can complete training. Authorities vet the groups.

- Most Member States have vetting procedures. However, they often only apply to a limited group of professionals, such as social workers or teachers. They do not cover all those in direct and regular contact with children. For example, they may not cover administrative staff and assistants.

- The police and/or judicial authorities provide specific certificates for people working with children in some Member States. This applies, for example, in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden.

- Vetting provisions are often, but not always, part of accreditation and licensing procedures.

- As a minimum, vetting procedures require checking criminal records. In particular, they are checked for sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children. Some countries have additional requirements, including mental health and psychological reports. These are requirements in Cyprus and Poland, for example.

- Very often it is service providers who must vet professionals. They must apply the provisions when recruiting staff. Nevertheless, state, regional and municipal authorities retain responsibility for implementing provisions. Systematically monitoring vetting procedure implementation is challenging given the plurality of service providers.

- Following initial checks, the frequency of reviews varies significantly. Some Member States have no provisions on the frequency of reviews and monitoring.

- Many Member States lack information and data on vetting.

- All Member States have requirements for vetting candidate foster parents. However, in at least Estonia, Greece, Lithuania and Slovenia, there are no mandatory provisions on review frequency.

All Member States have requirements for vetting candidate foster families upon initial selection. Nineteen Member States have provisions setting a specific timeline for the frequency of reviews: Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, France, Cyprus, Latvia, Hungary, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Finland.

Requirements vary significantly in these provisions. In Belgium (French community), for example, reviews take place every 5 years. In France and Romania, vetting is part of the licensing process of foster parents. These licenses must be renewed every 5 years in France and every 3 years in Romania.

In the Netherlands, foster parents are assessed annually. A new certificate of good conduct can be requested in assessments. In Ireland, general provisions require the police (Garda Síochána) clearance certificates to be renewed every 3–5 years.

In some Member States, such as Poland, the law establishes the frequency of reviews of foster parents’ health status and psychological suitability. However, there are no provisions requiring criminal record checks.

In other Member States, such as Greece, there are general provisions for initial requirements that apply throughout the placement period. These include a clean criminal record. There are, however, no specific provisions in place stipulating the frequency of and the procedure for reviews.

Regarding vetting of residential care, thirteen EU Member States have specific provisions for the frequency of reviews and checks following an initial vetting: Belgium (French community), Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Latvia, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania and Sweden.

In Latvia and Romania, for example, residential facility personnel undergo annual vetting. Latvia also assesses the personnel annually. In Bulgaria, assessment, including vetting, of personnel in these facilities takes place every three years.