Fundamental rights actors are formally included in the funding process but have little chance to influence decisions regarding the funds. Independent fundamental rights bodies and CSOs face challenges regarding participation in the funding process in the previous programming period. There is a lack of opportunities to participate and ineffective participation. This is despite requirements in the regulation for partnership and involvement (see legal corner below). The partnership principle in the CPR 21–27 explains that national authorities should draw on the expertise of fundamental rights actors from the very beginning of the process. A range of different challenges regarding participation occur throughout the various phases in the programming period, outlined below.

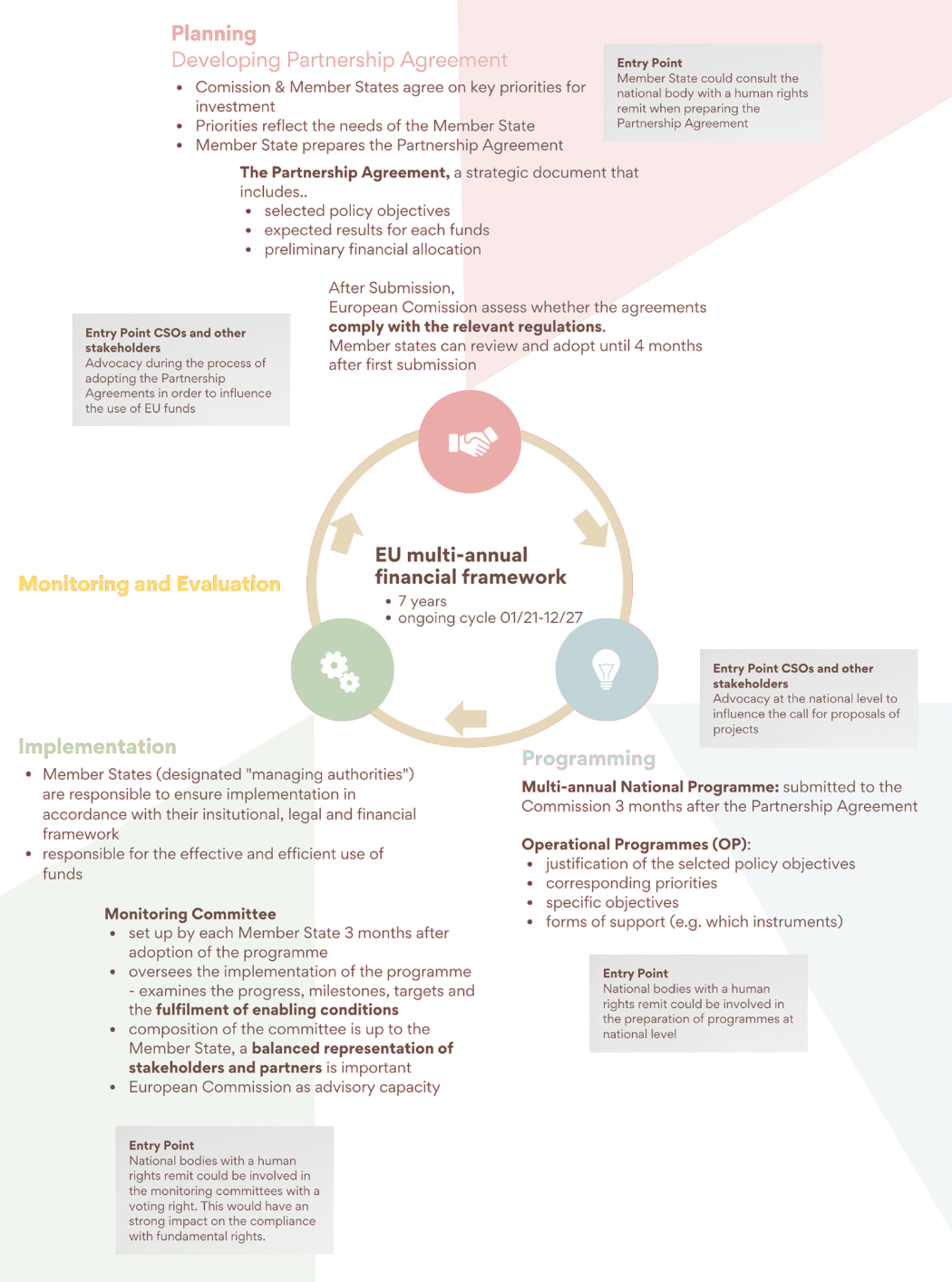

The EU programming period can be divided into different phases. Figure 2 shows potential entry points for the participation of independent fundamental rights bodies in the process.

Figure 2 – Entry points for independent fundamental rights bodies in the stages of the programming period

The diagram is a graphical representation of the EU multi-annual financial framework. The potential entry points for bodies with a human rights remit or civil society organisations to consult, monitor or advocate on behalf of their mandate are during the planning, implementation and programming phases. At planning stage the entry points are when a Member State could consult with the national body with a human rights remit when preparing the Partnership Agreement and when advocacy takes place during the process of adopting the Partnership Agreements in order to influence the use of EU funds. During the implementation phase the entry point occurs when national bodies with a human rights remit could be involved in the monitoring committees with a voting right. During the programming phase the entry points occur when there is advocacy at the national level to influence the call for proposals of projects and also if national bodies with a human rights remit are involved in the preparation of programmes at national level.

Source: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research (2023), The role of national human rights bodies in monitoring fundamental rights in EU funded programmes, Vienna

An overall finding is that both independent fundamental rights bodies and CSOs need to participate more at the early stages of the programming period. As a report by the European Network of Equality Bodies (Equinet) noted, participation in monitoring committees “tends to be the singular avenue opened up to equality bodies for their engagement with the European Structural and Investment Funds. This reflects a limited understanding of partnership on the part of managing authorities, whereby equality bodies should have the possibility to play a role at all stages” [45]

Equinet (European Network of Equality Bodies) (2022), Equality bodies and the European Structural and Investment Funds realising a potential for change, Brussels, p. 33.

.

A Commission representative suggested that early involvement of CSOs and independent fundamental rights bodies would help ensure their continued involvement in later stages of the programming period. They may be motivated to check what is happening regarding their input and would have greater awareness of the issues relating to funds governed by the CPR and the opportunities they could bring [46]

Interview with representatives of the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, 19 July 2022.

.

Research participants confirm that involvement of fundamental rights actors from the early stages is crucial for effectively integrating fundamental rights considerations into the funding process [47]

Interview with a Bulgarian CSO representative, 19 April 2022; interview with a representative of an intergovernmental organisation, 29 June 2022.

. Their expertise and reports on fundamental rights issues could be used to feed into the programming and to guide policy and investment priorities.

Based on the previous programming period, respondents to FRA’s research consider the preparatory phase to be when fundamental rights actors should be most closely involved and could have the most meaningful impact. As a Portuguese representative of an equality body notes, “[t]he critical stage is the political negotiation stage because that’s where the whole story begins. It’s like putting a train in motion, once you’re moving it’s more complicated to make detours” [48]

Interview with a Portuguese representative of the national equality body, 2022.

.

The same is true of the programming stage. One interviewee said “Programming is definitely the best time to influence it, because the moment the programme is adopted and confirmed in Brussels and by [the managing] authority, we don’t have much room for someone to say that this may not be in line with fundamental rights” [49]

Interview with a Croatian government official, 2022.

.

However, there are challenges in ensuring the proper participation of independent fundamental rights bodies and CSOs who are specialists in fundamental rights at the early stages.

First, the managing authority does not always invite fundamental rights actors to participate [50]

Interview with a representative of a CSO, 11 May 2022; interview with a representative of an umbrella organisation of independent fundamental rights bodies, 11 May 2022.

. Further, applications for membership of programming working groups are not always accepted.

For example, in Croatia, the ombudsperson’s request to participate in working groups was rejected. [51] Franet country report – Croatia, 2023, p. 9.

Croatian stakeholders also agreed that the range of actors consulted is not always as wide as it could be, with relevant organisations not always being fully integrated into the consultation process on the partnership agreement or programming [52]

Ombudsperson of the Republic of Croatia (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. The government of Croatia highlighted that there was consultation on its programmes. [53] E-mail response from Croatian National Liaison Officer, 2023.

As further examples, in Finland and Portugal, representatives from both CSOs and independent fundamental rights bodies point out that they are often not consulted or involved in the working groups preparing the partnership agreement or in the bodies responsible for the preparation of the programmes [54]

Interviews with Finnish independent fundamental rights bodies, May 2022; Franet country report - Portugal, 2023, p. 18.

. The relevant body may also choose to not be involved; the Cypriot Commissioner for Administration and the Protection of Human Rights, for example, decided not to participate at the preparatory stages to preserve its independence. For a discussion of the issue of independence and the involvement of independent fundamental rights bodies in work on EU funds, see Section 1.5 [55]

Ombudsman of Cyprus (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

.

Second, even when they are involved, fundamental rights actors’ voice might not be properly taken into account [56]

Interview with a representative of a CSO, 11 May 2022.

. Consultation in the early stages is not always meaningful. Either there is no opportunity to comment or there is insufficient time to do so, leading to what one CSO describes as “cosmetic feedback” to partnership agreements [57]

Interview with an Estonian CSO representative, 12 May 2022.

.

In Croatia, although the ombudsperson was invited to provide their views shortly just prior to the adoption of programmes, there was a lack of substantial consultation conducted and insufficient information available. Insufficient time for commenting and only informal consultations of fundamental rights actors taking place is also highlighted in a recent policy note. It also notes that access to and the quality of consultations also varies among different funds [58]

PICUM (Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants) and ECRE (European Council on Refugees and Exiles) (2023), Fundamental rights compliance of funding supporting migrants, asylum applicants and refugees inside the European Union, policy note, Brussels, p. 9.

. The government of Croatia notes that it held consultations on the programming document and that the public was kept informed through a website about the funds. [59] Representative of the national government of Croatia, 2023.

There may be other reasons fundamental rights actors are not involved at the early stages and sometimes the actors themselves are hesitant to get involved for valid reasons. A representative of an umbrella organisation of independent fundamental rights bodies notes a mix of issues related to capacity, independence and mandates [60]

Interview with a representative of an umbrella organisation of independent fundamental rights bodies, 11 May 2022.

.For a discussion on issues related to independence and mandates of independent bodies, see Section 1.5. Lack of capacity may prevent early involvement: as an Estonian CSO representative notes, referring to Estonian independent bodies, “I cannot imagine that the Chancellor’s or Commissioner’s Office would have this time to consult on all of this in the planning stage” [61]

Franet country report – Estonia, 2023, pp. 14–15.

.

Considering the wide range of issues that may come up in the management of the extremely disparate range of EU funds, which cover funding areas ranging from border security to social policy, keeping up with developments and getting involved can also be challenging. As a representative of one CSO puts it, “monitoring ESIF is very complicated and nobody is making it easy for anyone to check what’s going on” [62]

Interview with a representative of a CSO, 1 June 2022.

. Another CSO representative points out that “[i]f there is no will on the part of the Managing Authority, a lot can be hidden in the Partnership Agreement and the Operational Programmes and even when there are explicit references to potentially problematic issues from a fundamental rights perspective, you have to find it and follow-up” [63]

Interview with a representative of a CSO, 1 June 2022.

. For a wider discussion on capacity issues of independent fundamental rights bodies, see Section 2.2.

Other reasons for a lack of involvement of independent fundamental rights bodies include independent bodies or CSOs lacking awareness of the (significant) amount of funding involved, reducing the degree to which they prioritise the topic [64]

Interview with a representative of a CSO, 2 June 2022.

. In addition, as another CSO representative points out, NHRIs have traditionally been linked to UN institutions and so have been focused on UN and Council of Europe instruments, and less so on the Charter and cooperation with the EU [65]

Interview with a representative of academia, 26 August 2022.

. This may mean they have less experience dealing with EU issues, such as the applicability of the Charter.

The research indicates that there is both a lack of involvement and meaningful consultation of independent fundamental rights bodies and CSOs in the negotiation and programming phase and a lack of participation later in the programming period in some monitoring committees. More cooperation between independent fundamental rights bodies, CSOs and managing authorities has the potential for mutual learning and sharing of experiences.

Challenges may be noted here both in actual participation and in the utility and effectiveness of the participation that has occurred.

Participation in the monitoring committees is limited for both equality bodies and CSOs. Out of all Member States, only three bodies in Croatia, Finland and Sweden, which also function as equality bodies, took part in monitoring committees in the previous programming period. More generally, interviewees report that, during the previous programming period, the composition of monitoring committees was not always as wide as it could be. For example, some interviewees note that more CSOs working on gender equality should be included [66]

Interview with a national fund manager representative from Estonia, 2022.

. In relation to the current cycle, there was a lack of both human rights-related non-governmental organisations and non-governmental organisations dealing with women’s rights [67] Franet country report - Greece, 2023, p. 33.

.

Interviewees also highlight the challenge of the workload for monitoring committee members. Representatives from both CSOs and independent fundamental rights bodies note the highly technical and time-consuming nature of work on EU funds, with many pages of documents to work through but a lack of capacity and expertise to do so [68]

Ombudsperson of the Republic of Croatia (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available); interview with an Estonian CSO representative (EE/CSO/1), interview with representative from a Croatian equality body representative (HR/NHRB/04, p. 3); Ombudsperson of the Republic of Croatia (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. The Cypriot NHRI notes that this can affect the quality of the feedback and thus the overall monitoring of the funds [69]

Ombudsman of Cyprus (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. While the technical and time-consuming nature of the work on EU funds is inherent to responsible fund allocation, targeted documents highlighting relevant information, adequate resources, investment in modern digital infrastructure and tools and training can help enhancing the quality of the monitoring process [70] ) Comment by National Liaison Officer from Latvia, 2023.

.

CSOs also mention that the information provided to participants in the monitoring committee is too abstract and general for a meaningful fundamental rights analysis [71]

Interview with an Estonian CSO representative, 2022; Interviews with Latvian CSO representatives; see Ombudsman’s Office of the Republic of Latvia, (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. The lack of detailed and fundamental rights-specific information and discussions may partially explain why fundamental rights actors find it difficult to engage with the monitoring committees in an efficient manner [72]

Interviews with representatives from independent fundamental rights bodies; see Franet country report - Croatia, 2023, p. 15; Interviews with Latvian CSO representatives; Ombudsman’s Office of the Republic of Latvia, (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

and why CSOs do not always answer fund managers’ calls to participate in monitoring committees [73]

Interview with an Estonian national fund manager representative, 2022.

.

When it comes to the quality of participation, fundamental rights actors often feel that they lack real influence and that the meetings have not provided the possibility for genuine discussion on fundamental rights issues. For example, the Croatian NHRI notes in its report, referring to the previous programming period, that the ombudsperson’s office was involved in two monitoring committees in an advisory role, but that its effective participation was hampered by a lack of any substantive discussion on fundamental rights issues [74]

Ombudsperson of the Republic of Croatia (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

.

Similarly, CSOs in Latvia feel “as if the Monitoring Committee has been set up due to requirements in the EU framework, but the activity is very formal to show that civil society is included” [75]

Ombudsman’s Office of the Republic of Latvia, (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. The national administration underlines that involvement in the Monitoring Committee is not limited but depends on the interest and capacity of CSOs. It also highlighted that improved communication and collaboration can enhance the quality of discussions and outcomes within Monitoring Committee.[76] ) Comment by the Latvian National Liaison Officer, 2023.

A report from Equinet also highlights the lack of meaningful engagement and discussions, noting that equality bodies perceive their influence on decisions taken in monitoring committees as limited [77]

Equinet (2022), Equality bodies and the European Structural and Investment Funds realising a potential for change, Brussels, p. 33.

. As one interviewee notes, highlighting a perceived lack of added value in participation in work on EU funds: “Another issue is that the advantages of being involved in this process is not clear for the members. It would take a lot of time to prepare and then recommendations are not listened to […] it can be overwhelming […] it takes away their opportunities to focus on areas where they can reach impact” [78] Interview with a representative from a European human rights organisation, 11 May 2022.

.

CSO representatives also feel that their comments on fundamental rights issues are often not fully taken into account. One Estonian CSO representative describes the involvement of fundamental rights actors in monitoring committees as a “box-ticking exercise” [79]

Interview with an Estonian CSO representative, 2022.

. In Latvia, some CSOs acknowledge that they are being heard and could influence processes, while others describe an overly formal process in which CSOs feel powerless [80]

Ombudsman’s Office of the Republic of Latvia, (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. While formalities may often be just the result of bureaucratic complexities, it is submitted that further efforts could streamline the process and make it more accessible for CSOs.

Another issue reported, especially by CSO representatives, is that either fundamental rights actors lack voting rights or their suggestions are outvoted in monitoring committees by government entity representatives, who form the majority [81]

Franet country report - Bulgaria, 2023, p. 8.

. One civil society respondent from Bulgaria, where government officials form an absolute majority in the committees, states that “NGOs [non-governmental organisations] presently play the role of a government decisions’ confirmation mechanism” [82] Franet country report - Bulgaria, 2023, p. 17.

.

There are also complaints that other types of CSOs, such as trade unions or employers’ organisations, have more influence than non-governmental organisations (NGOs), as they are consulted more frequently by the government throughout the programming period [83]

Interviews with CSO representatives, see Franet country report - Bulgaria, 2023, p. 8.

. An Equinet report [84]

Equinet (2022), Equality bodies and the European Structural and Investment Funds realising a potential for change, Brussels .

also highlights concerns among equality bodies that an economic focus dominates the considerations of the monitoring committees. In addition, CSO representatives in Portugal refer more generally to a concern that there is a focus on the financial execution of the financed projects, rather than the execution of the goals [85]

Equinet (2022), Equality bodies and the European Structural and Investment Funds realising a potential for change, Brussels, p. 33.

.

Overall, there is clearly a need for more involvement of both independent fundamental rights bodies and specialised fundamental rights CSOs and to ensure that they can take part in a meaningful way in the work of the monitoring committees. Such involvement should enable them to engage in an effective assessment of fundamental rights compliance of the use of funds. In addition, fundamental rights compliance is a legal obligation and not a matter of voting in a committee. Concerns raised by CSOs or others on fundamental rights matters should be treated with the requisite care in the work of the monitoring committees.

Another area in which fundamental rights actors can potentially participate is evaluation. According to Article 44 of the CPR 21–27, the Member State or the managing authority must carry out evaluations of the programmes. In addition to effectiveness, evaluations of efficiency, relevance and coherence “may also cover other relevant criteria, such as inclusiveness, non-discrimination and visibility”.

In addition to the evaluations required under Article 44 of the CPR 21–27, Article 41 (7) states that annual performance reviews are to be conducted by the Member States and submitted to the Commission for programmes support by the AMIF, BMVI and ISF. In accordance with Article 8 of the CPR 21–27, which focuses on partnership and multilevel governance, the partners listed in the article should be included in the process of evaluating programmes.

The findings of evaluations can help ensure that new operations in the field of fundamental rights are (more) effective and that operations that violate fundamental rights are not continued and can be better avoided through future programming. Evaluations can also identify operations that would have had the potential to promote fundamental rights and can point to ways to harness such potential in future activities. A key challenge in this regard is the lack of appropriately disaggregated data to populate indicators showing the positive impact of fund operations targeting those in situations of vulnerability [86]

Interviews with representatives of independent fundamental rights bodies; see Franet country report - Croatia, 2023, p. 16; Franet country report - Greece, 2023, p. 40.

.

Common output and result indicators for evaluations are identified in annexes to the specific regulations covering each of the funds. These indicators are useful, but appropriately disaggregated data (for instance by racial or ethnic origin, disability or sexual orientation) to populate them across the EU are lacking. This can then result in a lack of evidence on how fundamental rights obligations are fulfilled, as it may not be known whether funds are reaching the intended target audience or whether certain categories of persons tend to be excluded from benefiting from the funds [87]

Franet country report - Greece, 2023, p. 40.

..

In a recent report, the European Court of Auditors found that there is insufficient information on how many people with disabilities benefit from EU funding, and to what extent they benefit from it. [88] European Court of Auditors (2023), Supporting Persons with Disabilities-practical impact of EU action is limited, pp. 34-35.

It also found that the horizontal enabling condition does not serve as a tool to ensure better targeting of EU funding. [89] European Court of Auditors (2023), Supporting Persons with Disabilities-practical impact of EU action is limited, pp. 38-39.

However, the research also highlights some positive initiatives in this regard. For example, in Portugal, the fundamental rights impact is also measured in evaluations [90]

See, for example, Agency for Development and Cohesion (2021), Portugal 2020: Annual Report 2020 (Portugal 2020: Relatório Annual 2020), Lisbon.

.

At the same time, there appears to be room for more emphasis on fundamental rights. For instance, in Croatia, an evaluation for a 2014–2020 programme identifies a need for better measurement of fundamental rights impacts [91]

Interviews with representatives from independent fundamental rights bodies; see Franet country report - Croatia, 2023, pp. 16–17.

. In Greece, non-discrimination on the grounds of disability and accessibility are included as criteria for the selection of operations to be covered by programmes; however, actual outcomes could not be properly evaluated because there was no appropriate assessment mechanism based on actual results [92]

Franet country report - Greece, 2023, p. 34.However, see Special Management Service of the South Aegean Region (2020-2021), Program Evaluations and EEO Group (2021) Final Evaluation Report.

.

Independent fundamental rights bodies can contribute, along with specialised fundamental rights CSOs, to programme evaluations by highlighting the fundamental rights perspective and providing relevant recommendations [93]

Franet country report - Bulgaria, 2023, p. 21; Franet country report – Finland, 2023, p. 15.

. This would require these bodies to use the existing indicators – or propose additional indicators – to evaluate fundamental rights aspects of the programmes, in particular compliance with the relevant horizontal and thematic enabling conditions.

More impact-oriented reporting and evaluation can help to determine whether fundamental rights are given sufficient priority in terms of resources and whether fundamental rights-related goals are identified and achieved, and to examine what improvements may be needed to enhance fundamental rights mechanisms or to see what areas require extra resources. In addition, participants in the FRA workshop for civil society organised in December 2022 highlight that peer learning and networking are crucial among stakeholders involved in monitoring EU funds and their evaluations, focusing on different themes.

Another finding of the research at national level is that there is sometimes a lack of communication and coordination in the context of EU funds and fundamental rights. As the Polish NHRI report points out, all “[i]nstitutions involved in EU funds implementation should be aware and actively engaging in securing the respect of the Charter within their actions at all stages […]. This means that [the] general scheme of EU funds implementation should be translated into concrete mechanisms and checks starting from design of financing programmes to the stage of clearance of individual contracts and projects” [94]

Polish Commissioner for Human Rights (2023), ‘The role of national bodies with a human rights remit in ensuring fundamental rights compliance of EU funds’, report written in the framework of the FRA project “Supporting National Human Rights Institutions in monitoring fundamental rights and the fundamental rights aspects of the rule of law” (not yet publicly available).

. This is possible only by ensuring cooperation and coordination between all relevant actors.

Participants in the roundtable in France highlight the need to facilitate discussions between project operators and managing authorities [95]

France, roundtable report, p. 9.

. In Finland, the roundtable participants and interviewees likewise highlight the need for more discussions between all those involved in the programming period, including independent fundamental rights bodies [96]

Finland, roundtable report, p. 6.

.

Research participants note a lack of continuous communication between managing authorities and civil society and independent fundamental rights bodies, and a lack of a participatory approach [97]

Interview with a civil society representative from Portugal, 9 May 2022; interview with a national fund manager representative from Croatia, 28 April 2022; FRA consultation of experts, NHRI project, 27 March 2023.

. This may be partly because the relevant authorities are not aware of the partnership principle, as established by the CPR 21–27. As became evident in the national context, awareness of the provisions of the CPR 21–27 is sometimes limited among relevant actors, including the managing authority [98]

Germany, roundtable report, pp. 7–8.

.

In 2022, the European Network of National Human Rights Institutions (ENNHRI) issued a statement regarding participation in the programming period. It highlighted that NHRIs should participate only in an advisory capacity and that “in line with their independence, it is inappropriate for NHRIs to take up a decision-making or voting position in the context of the CPR, or to issue ‘fundamental compliance certificates’ to state authorities in advance of the EU funded projects being implemented” [99]

ENNHRI (European Network of National Human Rights Institutions) (2022), Monitoring Fundamental Rights Compliance of EU Funds – Potential role, opportunities and limits for NHRIs, Saint-Gilles, Belgium, p. 2.

. The ENNHRI position refers to the UN Paris Principles, that is, the set of rules that govern the functioning of NHRIs [100]

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (1993), ‘Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (the Paris Principles)’.

. Similar considerations also apply to ombudspersons, who must not “engage in political, administrative or professional activities incompatible with his or her independence or impartiality” [101]

See European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) (2019), Principles on the protection and promotion of the ombudsman institution (the Venice Principles), Opinion No 897/2017, point 9.

, and to equality bodies, which are also expected to be independent [102]

See, for instance, Commission Recommendation (EU) 2018/951 of 22 June 2018 on standards for equality bodies (OJ L 167, 4.7.2018, p. 28), the purpose of which is “to set out measures that Member States may apply to help improve the equality bodies' independence and effectiveness”.

.

Any involvement does not necessarily compromise the independence of independent fundamental rights bodies, but a structural engagement with public authorities in the programming period might compromise the perception of the institution’s independence. The impact of this type of engagement on institutions’ independence requires a case-by-case assessment that takes the overall mandate and role of the institution in question into account.

In FRA’s research, many independent fundamental rights bodies themselves raise concerns regarding independence and highlight the need to avoid involvement in decision-making [103]

See Franet country report – France, 2023, p. 10; Franet country report – Estonia, 2023, p. 12; Franet country report – Germany, 2023, p. 25; Franet country report – Finland, 2023, pp. 15–16.

. In some Member States, such as Cyprus, Croatia, Finland and Poland, the independent fundamental rights bodies participate in monitoring committees as observers with a consultative role only (i.e. providing advice without formally participating in any decision-making). The Estonian NHRI declined an invitation to become a member of a monitoring committee, seeing it as not in line with its independent role [104]

Franet country report – Estonia, 2023, p. 12.

.

However, in other Member States, such as Greece, independent fundamental rights bodies, more specifically the Greek National Commission for Human Rights (GNCHR) and the ombudsman, became voting members of the AMIF monitoring committee for the 2014–2020 programming period later in the process [105]

Franet country report – Greece, 2023, p. 35-36.

. For the current programming period, Greece has signed a partnership memorandum with the GNCHR stating that the body will provide advice throughout the programming period and participate in the monitoring committees [106]

Franet country report – Greece, 2023, p. 5.

. The monitoring committee for the Migration and Home Affairs fund includes CSOs, international organisations, the ombudsman, the National Confederation of Disabled People and the Fundamental Rights Officer in the Ministry of Migration and Asylum. [107] Greece (2023) Ministerial Decision dated 02 October 2023 (Protocol No 457538/02.10.2023),

During the previous programming period, the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency in Germany (FADA) was regularly consulted on anti-discrimination issues but did not have a formal seat in any monitoring committee, and recommendations issued by FADA were not always taken into account. In the new programming period, the role of FADA has been strengthened. FADA has secured an official seat in the ESF+ monitoring committee, with not only voting rights but also a veto right. The managing authority has to consider any recommendations by FADA [108]

Equinet (2022), Equality bodies and the European Structural and Investment Funds realising a potential for change, Brussels, pp. 40–41.

.

Overall, it is for independent fundamental rights bodies themselves to decide what role is appropriate for them to play. Various considerations can come into play here, including the nature of the work of these bodies (i.e. in an advisory role rather than as part of the executive branch of government), what voting for or against certain positions in monitoring committees might mean for their later ability to deal independently with complaints against those decisions, and potential clashes between being seen as politically neutral and statements on spending priorities. Not every EU Member Stater currently has an NHRI, or one that fully complies with the Paris Principles and the respective mandates of such bodies often differ significantly [109] For an overview, see FRA (2022) December 2022 update - NHRI accreditation status and mandates

. FRA has repeatedly taken the position that all Member States “should have independent, effective and impactful NHRIs that comply with the Paris Principles to deliver and promote human and fundamental rights more effective” [110] FRA (2020), Strong and Effective National Human Rights Institutions, p. 12.

. Overall, it appears possible, however, for independent fundamental rights bodies to participate in each part of the monitoring cycle if they maintain an appropriate level of restraint and base their actions on the principles of international human rights law. It would be useful if governments were to extend an invitation to all independent fundamental rights bodies to participate in the monitoring committees. In line with their independence, these bodies could then decide whether to participate or not based on their own analysis and institutional practice. However, they will need sufficient capacity to act as discussed in the following section.