Article 12 of the CRPD requires States Parties to recognise that all persons have the right to equal recognition before the law. They should take measures to ensure that persons with disabilities receive support in exercising their rights and provide safeguards against abuse. Considering Article 12 a non-derogable right, the CRPD Committee noted that people may never be deprived of their legal capacity based on their disability.

Legal capacity is the ability to hold rights and duties (legal standing) and to exercise those rights and duties (legal agency). It is the key to accessing meaningful participation in society. Mental capacity refers to the decision-making skills of a person, which naturally vary from one person to another and may be different for a given person depending on many factors, including environmental and social factors.

CRPD Committee, General comment No 1 (2014)

During the reporting period, the CRPD Committee has consistently deplored the discriminatory nature of national provisions that deny or restrict the right to vote of persons deprived of legal capacity, in:

- Cyprus (Concluding observations on the initial report of Cyprus (2017), paragraph 57);

- Czechia (Concluding observations on the initial report of the Czech Republic (2015), paragraph 57);

- Estonia (Concluding observations on the initial report of Estonia (2021), paragraph 56);

- Greece (Concluding observations on the initial report of Greece (2019), paragraph 42);

- Hungary (Concluding observations on the combined second and third periodic reports of Hungary (2022);

- Italy (Concluding observations on the initial report of Italy (2016), paragraph 73);

- Lithuania (Concluding observations on the initial report of Lithuania (2016), paragraph 57);

- Luxembourg (Concluding observations on the initial report of Luxembourg (2017), paragraph 50), paragraph 56);

- Poland (Concluding observations on the initial report of Poland (2018), paragraph 51);

- Portugal (Concluding observations on the initial report of Portugal (2016), paragraph 55);

- Slovenia (Concluding observations on the initial report of Slovenia (2018), paragraph 49).

Research FRA conducted in 2019 found slow but steady progress in realising the right to vote for all, although two thirds of EU Member States in one way or another restricted the right to vote of people deprived of legal capacity.

The ECtHR has required a specific court decision for depriving any person of the right to vote under Article 3 of Protocol No 1 to the ECHR (Strøbye and Rosenlind v Denmark, Nos 25802/18 and 27338/18, 2 February 2021; Caamaño Valle v Spain, No 43564/17, 11 May 2021). Most recently, the ECtHR held in Anatoliy Marinov v Bulgaria (No 26081/17, 15 February 2022) that ‘indiscriminate removal of the voting rights of the applicant – without an individualised judicial review and solely on the basis of the fact that his mental disability necessitated that he be placed under partial guardianship – cannot be considered to be proportionate’.

The following sections look at policy, legal and practice developments in the EU and in the Member States. They are increasingly moving towards legally recognising all people’s capacity to participate in elections.

Across the EU, ‘persons with disabilities, especially those deprived of their legal capacity or residing in institutions, cannot exercise their right to vote in elections and … participation in elections is not fully accessible’, the CRPD Committee noted with concern in the very first concluding observations on the initial report of the EU in 2015. The Committee recommended that the EU ‘take the necessary measures, in cooperation with its member States and representative organizations of persons with disabilities, to enable all persons with all types of disabilities, including those under guardianship, to enjoy their right to vote and stand for election, including by providing accessible communication and facilities’ (paragraphs 68–69). Considering the Committee’s conclusions, this section summarises what the EU has done to address the Committee’s concerns.

In the European disability strategy, the European Commission recognised that persons with disabilities face difficulties in participating in the democratic process, partly due to legal capacity restrictions. It therefore announced in the strategy that it would work with Member States to guarantee political rights of persons with disabilities on equal basis with others. Furthermore, in its democracy action plan, the Commission highlighted that it would strive to ensure inclusiveness and equality in democratic participation. The European Commission encourages Member States to ‘prevent and remove the barriers they encounter when participating in elections’ and to ‘review the possibility for the blanket removal of electoral rights of persons with intellectual and psycho-social disabilities without individual assessment and possibility of judicial review’ (Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/2829 of 12 December 2023 on inclusive and resilient electoral processes in the Union and enhancing the European nature and efficient conduct of the elections to the European Parliament, recital 22).

In 2022, the European Parliament proposed a new EU electoral law hat seeks to repeal the current European Electoral Actand adopt a new regulation governing European elections. The aim is to establish a uniform procedure for European elections, increase the turnout of Union citizens and strengthen the European dimension of the elections. According to the proposal (which has not been so far adopted; see Legal corner 2), every EU citizen from 16 years of age, including people with disabilities and regardless of their legal capacity, will be granted the right to vote in the elections to the European Parliament.

In its conclusions on the protection of vulnerable adults across the European Union (2021), the Council of the European Union calls on the Member States to promote greater awareness of the 2000 Hague Convention on the International Protection of Adults and to bring forward procedures to ratify it or to hold consultations on possible accession. Seventeen Member States have ratified this convention. It ‘applies to the protection in international situations of adults who, by reason of an impairment or insufficiency of their personal faculties, are not in a position to protect their interests’ (Article 1(1)). It provides rules on jurisdiction, applicable law, and international recognition and enforcement of protective measures, and establishes a mechanism for cooperation between the authorities of contracting states in matters relating to the protection of adults. The outline of the Convention also notes that it furthers some important objectives of the CRPD, in particular those of Article 12 on equal recognition before the law, Article 18 on liberty of movement and nationality, and Article 32 on international co-operation.

Considering the Hague Convention an efficient private international law instrument, the European Commission proposed a regulation on jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition and enforcement of measures and cooperation in matters relating to the protection of adults, in 2023. The proposed regulation must be interpreted in accordance with the EU Charter and the CRPD (recital 15). While promoting the right to autonomy and the right to be heard, the proposal introduces exceptions in Article 10 of the Regulation for exceptional circumstances. Furthermore, the proposal allows the placing of a person in an institution (Article 21). DPOs and two UN special rapporteurs criticised these aspects of the proposal as promoting substitute decision-making (Legal corner 3) contrary to the CRPD. The UN special rapporteurs especially noted that the proposal should consistently make it clear that substitute decision-making or institutionalisation as a protective measure would not be consistent with the CRPD.

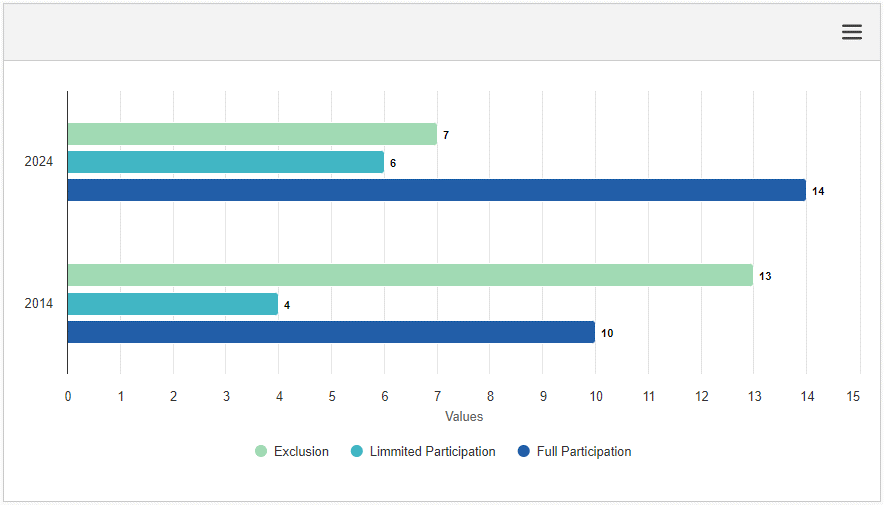

Figure 1 – Numbers of Member States in 2014 and 2024 giving people deprived of legal capacity the right to vote

Alternative text: A comparative chart showing the number of Member States in 2014 and 2024 allowing people deprived of legal capacity to vote. People with disabilities could participate fully in 10 states in 2014 and in 14 states in 2024. They had limited participation in 4 states in 2014 and in 6 states in 2024. They were excluded in 13 states in 2014 and in 7 states in 2024.

Source: FRA, 2024.

By the end of 2023, laws in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Malta, Poland and Romania provided for automatic exclusion of people under legal guardianship from the voting process. Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden ensure full participation of people with disabilities in the electoral process. The trend in this regard has been positive over recent years, as FRA’s 2019 report noted.

Four Member States recently amended their constitutions or laws to remove automatic or other restrictions on voting rights based on legal capacity. France repealed a national provision according to which the guardianship judge could suspend the voting rights of a protected adult. Consequently, 300 000 adults under guardianship who had been deprived of their right to vote by a court decision recovered this right. As a result, 3 000 of them voted in the last European elections (Ministry of the Interior, Le vote des personnes handicapées; Loi n° 2019–222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation 2018–2022 et de réforme pour la justice; Franet).

In Luxembourg, a revision of the Constitution in early 2023 repealed the automatic exclusion of adults under guardianship from the right to vote and to stand for election. Along with this development, the 2003 Electoral Act was amended to give adults placed under guardianship the right to vote in local, national and European elections for (Loi du 17 janvier 2023 portant révision des chapitres IV et Vbis de la Constitution; Loi du 4 février 2005 relative au référendum au niveau national, Articles 2(3) and 12; Communication relative au paquet de mesures en vue de rendre les élections plus accessibles aux personnes handicapées (2023)).

In Ireland, a legislative amendment entered into force in 2023 allowing the implementation of the provisions of the 2015 Act. That includes abolishing the wardship system and introducing a statutory framework of supported decision-making for adults. Under the new law, everyone is presumed to have decision-making capacity. People should be supported to make their own decisions. However, in some circumstances, capacity is assessed based on the person’s ability to make a specific decision at a specific time (Houses of the Oireachtas, Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) (Amendment) Act 2022; Circuit Court, ‘Assisted Decision Making (Capacity) Act – General information’).

Similarly, Slovenia adopted supported decision-making by amending Article 79 of the Election of Members of the European Parliament Act in 2024. The amended text provides that people with mental and intellectual disabilities may be assisted by a person of their choice when voting at the polling station. The law no longer allows courts to deprive people of voting rights based on mental disability.

Some Member States that provide for restrictions announced in their strategies and action plans that they intend to take actions towards removing the restrictions. For example, Poland announced that it will make the necessary changes to the legislation regarding the acquisition of the right to vote and the right to stand for election (Council of Ministers, Uchwała nr 27 w sprawie przyjęcia dokumentu Strategia na rzecz Osób z Niepełnosprawnościami 2021–2030 (2021)). Belgium (Federal Public Service Social Security, Plan d’action fédéral handicap 2021–2024, pp. 44–45) and Cyprus (Department of Labour, Welfare and Social Insurance, Department of Social Integration of Persons with Disabilities, Πρώτη Εθνική Στρατηγική για την αναπηρία 2018–2028 και Δεύτερο Εθνικό Σχέδιο Δράσης για την αναπηρία 2018–2020 (2022)) will examine how to reduce deprivation of legal capacity to vote for people under guardianship.

In some cases, when the law provides for automatic exclusion from voting and standing for elections for people deprived of their legal capacity, judicial practice played an important positive role. The Romanian Constitutional Court held that the guardianship system was unconstitutional, as it had not been accompanied by sufficient guarantees to ensure respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. The court found Article 164(1) of the Civil Code, allowing for the placement of a person under legal guardianship, unconstitutional and contrary to Article 12 of the CRPD. The contested provision did not consider varying degrees of ‘capacity’ and provide for periodic review of the protection measure, the court noted (Romanian Constitutional Court, press release, 16 July 2020).

In Poland, the Nowy Sącz District Court found that the blanket deprivation of the right to vote in European Parliament elections for people partially deprived of legal capacity violates the ECHR, the CRPD and EU law. Any exclusion from participation in elections should be preceded by an individual assessment of a person’s situation. The court held that the applicant’s health condition would have allowed him to cast his vote (case No I Ns 376/19, 19 April 2019).

Estonia’s Civil Code provides for an automatic restriction of voting rights. However, the Supreme Court considered that people deprived of their legal capacity were not to be considered incapacitated with respect to their right to vote (Decision No 3-2-1-32-17,19 April 2017; Chancellor of Justice, reply to FRA’s questionnaire, 10 November 2023).

However, not all judicial decisions necessarily recognise legal capacity in relation to political participation. In Slovenia, the Supreme Court held that the right to vote of people who are found to be genuinely unable to understand the meaning, purpose and effects of elections can be restricted in the public interest. Article 29 of the CRPD does not contain rights but rather lists various sets of benefits that countries must provide to persons with disabilities, the court noted (Judgment No X Ips 29/2021, 23 February 2022).

Under Article 13 of the CRPD, States Parties must ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others, including through the provision of reasonable accommodations. This section explores whether all people (especially those deprived of their legal capacity) are legally able to access complaints mechanisms when they have not been able to exercise the right to political participation.

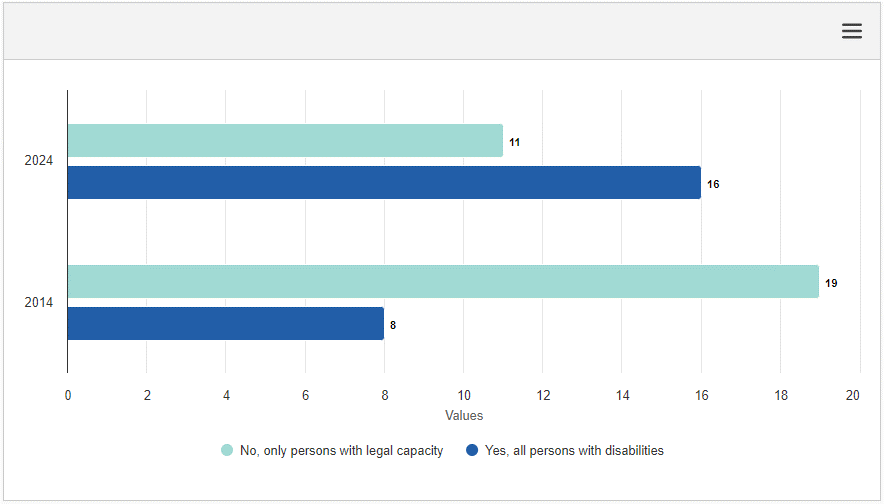

In 16 Member States, all persons with disabilities have access to a complaints mechanism if they have not been able to exercise their right to vote. Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechia, Greece, France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland and Romania give only people with legal capacity access to complaints. People under guardianship may sometimes complain before ombuds institutions, for instance in Croatia (Ombudsperson for Persons with Disabilities, Izvješće o radu Pravobraniteljice za osobe s invaliditetom 2021), Cyprus (Ombudsman of Cyprus) and Greece (Article 4 of Law 3094/2003 on the Greek Ombudsman’s operation). The ability to complain may also depend on the scope of the person’s legal capacity as decided by the national court, for example in Czechia (information provided by Franet).

Figure 2 – Numbers of Member States in 2014 and 2024 where people with disabilities are legally able to access complaints mechanisms

Alternative text: A comparative chart showing the numbers of Member States in 2014 and 2024 where people with disabilities have legal access to complaints mechanisms. The question asked was ‘Are all persons with disabilities legally able to access complaints mechanisms if they have not been able to exercise the right to political participation?’ The answer was ‘yes’ in 8 states in 2014 and in 16 states in 2024. The answer was ‘no, only people with legal capacity’ in 19 states in 2014 and in 11 states in 2024.

Source: FRA, 2024.

Few specific actions of Member States aim to ensure that people deprived of legal capacity can exercise their right to vote. Only two examples were found: one in Belgium (Federal Public Service Social Security, Plan d’action fédéral handicap 2021–2024, p. 45) and one in Czechia (Government Board for Persons with Disabilities, National plan for the promotion of equal opportunities for persons with disabilities 2021–2025 (2020), pp. 74). The two countries indicated generally that they will adopt measures to ensure that people deprived of legal capacity can exercise the right to vote.